The Questioner and the Republic. On Alexander Karp’s Moral Vision of Technology.

Alexander Karp’s The Technological Republic calls for a renewal of conviction equal to our power. In an age rich in intelligence but poor in purpose, he argues that freedom, beauty, and belief must once again guide what we build—and why.

Alexander C. Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska’s The Technological Republic is the most paradoxical technologist’s book in recent memory: an exciting brief against drift written from inside the engine room. It reads less like a Valley memoir than a needed secular homily on ends and means. “The grandiose rallying cry of a generation of founders in Silicon Valley was simply to build,” they write. “Few asked what needed to be built, and why.”

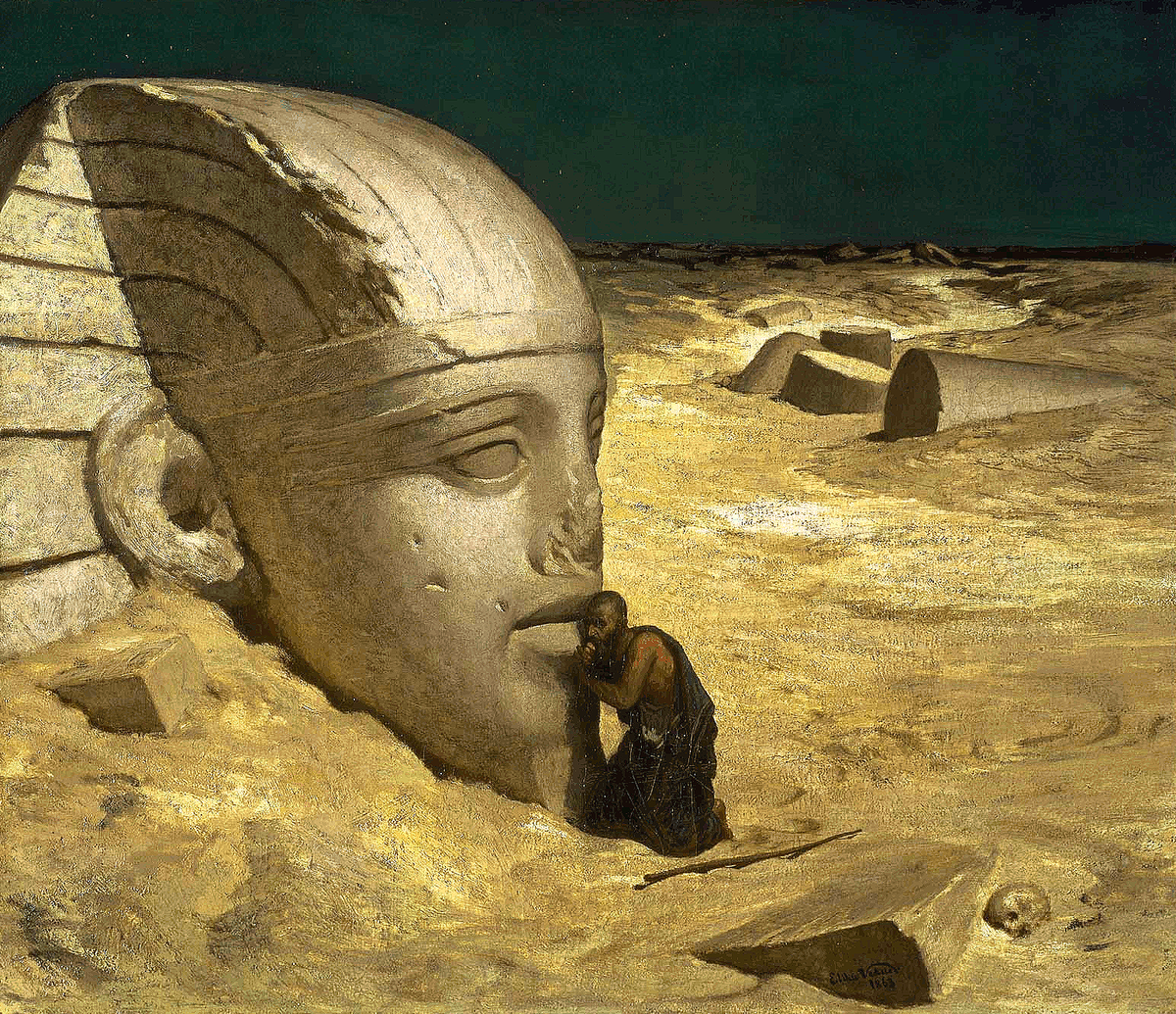

That single provocation frames the book’s central diagnosis: technological mastery has outpaced moral purpose. We command code yet doubt meaning; we perfect mechanism and neglect telos. The West still enjoys formidable “hard power”—economic scale, military reach, algorithmic prowess—but has misplaced the “soft belief” that once directed those powers. In Karp and Zamiska’s telling, this is the tragedy of the technological republic: a civilization that can model everything except its own ends. The “vital yet messy questions” about the good life and our shared projects, they note, have been treated as anachronisms—and the result is misdirection of capital and talent toward the trivial.

The “vital yet messy questions” about the good life and our shared projects, they note, have been treated as anachronisms—and the result is misdirection of capital and talent toward the trivial.

The argument is thoroughly historical. The twentieth-century blend of science and statecraft—Vannevar Bush, Sputnik, NASA—made public progress legible and legitimate. When leaders deliver advances that serve the common good, political authority earns indulgence; when emerging technologies enrich without advancing the public interest, legitimacy crumbles. “Trouble often follows.” The authors insist this is not nostalgia for Big Government but a plea for a renewed compact: the engineering elite must help articulate a national project and defend a liberal order whose protections made Silicon Valley possible in the first place.

Beneath the policy brief lies a deeper cultural critique. For decades, the Valley wrapped itself in world-saving rhetoric while channeling its genius into photo-sharing, ad-targeting, and life-hacking. Karp and Zamiska anatomize the drift: the market rewarded “shallow engagement,” the best minds turned inward, and collaboration with the state atrophied. The result is aimlessness by coders—what Max Weber would have recognized as disenchantment, the fate of a world that has learned to calculate everything except its own worth. For Weber, the modern project of rational mastery dissolved the sacred canopy that once gave action meaning. Science could explain how, but not why; bureaucracy could perfect means, but not ends. In Karp and Zamiska’s Technological Republic, that disenchantment has entered its algorithmic phase. The old priesthoods have vanished, replaced by engineers who treat belief itself as error—“the enemy,” as they write—and who find transcendence only in computation.

The old priesthoods have vanished, replaced by engineers who treat belief itself as error—“the enemy,” as they write—and who find transcendence only in computation.

Against the cultural drift they diagnose, Karp and Zamiska argue that the foundations of Western success, including technological innovation, rely on more than just unfettered freedom. They emphasize the importance of underlying structures and shared beliefs. They state plainly that "the protection of individual rights against state encroachment" provided the essential conditions "without which the dizzying ascent of Silicon Valley would never have been possible".

However, they argue this framework requires "soft belief"—a shared conviction and purpose—to be truly productive. When this belief erodes, as they contend it has, freedom loses its direction. The result is a "hollowing out of the American project", where immense technical capacity is squandered. Silicon Valley "turned inward," focusing talent on the "trivial and ephemeral" instead of addressing "greater security and welfare". The peril they identify is not tyranny, but this drift—a civilization possessing the mechanisms of freedom but lacking the "coherent collective identity or set of communal values" that once gave it purpose.

This is where the authors’ analysis, perhaps unwittingly, resonates strongly with the philosophical anthropology of Karol Wojtyła (John Paul II), though they do not cite him directly. Wojtyła, particularly in The Acting Person, emphasized freedom as conscious, responsible action—"self-possession through self-governance" rooted in choosing the good. Karp and Zamiska echo this call for integrated belief and action when they lament the "abandonment of belief" in the West and critique its "soft belief" in contrast to its "hard power".

They specifically target a generation of “technological agnostics,” brilliant engineers left “unmoored from any sense of national purpose.” Their critique is that the prevailing “techno-utopian view” in Silicon Valley has devolved into a “narrow and thin utilitarian approach… one that casts individuals as mere atoms in a system to be managed and contained.” The comparison with Karol Wojtyła’s thought could not be sharper. In The Acting Person (1969), Wojtyła argued that the human being cannot be understood through external functions, data points, or collective statistics, but only through interior self-determination. Action, for him, is not a mechanical output but a revelation of the person’s moral structure: through freely chosen acts, the self becomes both subject and author of meaning. Freedom, therefore, is not the liberty to manipulate but the capacity to be responsible for oneself in truth. Wojtyła warned that modernity’s greatest temptation was the pulverization of the person—reducing the human subject to fragments of behavior, social function, or productive capacity. This atomization, he wrote, breeds alienation: the loss of interior unity that makes self-governance possible.

Karp and Zamiska describe precisely this condition in technological form—a culture of “technological agnostics,” brilliant yet detached, where individuals are treated as “mere atoms in a system to be managed and contained.” Their “narrow and thin utilitarian approach” mirrors what Wojtyła saw as the collapse of the personal into the functional, the moral into the mechanical. Against such reduction, both the philosopher-pope and the technologists turned moralists insist on recovering the indivisibility of the person—the only foundation on which freedom can still stand.

Their “narrow and thin utilitarian approach” mirrors what Wojtyła saw as the collapse of the personal into the functional, the moral into the mechanical. Against such reduction, both the philosopher-pope and the technologists turned moralists insist on recovering the indivisibility of the person—the only foundation on which freedom can still stand.

Karp and Zamiska’s “technological agnostics” embody the inversion of that vision—creators detached from conscience, exercising power without interior reference. Where the utilitarian mindset measures value in efficiency or scale, Wojtyła insists on participation: every person’s inclusion in the shared pursuit of the common good. To treat human beings as variables to be optimized is, in his language, a form of depersonalization—a rupture in the moral order of creation. The authors’ warning that innovation has become “disinterested in the public project and reason for being” thus echoes Wojtyła’s own diagnosis of alienation: a freedom emptied of truth, action severed from responsibility.

What does responsible action look like in such a world? For Karp and Zamiska, it involves accepting the moral burden of building necessary tools, even difficult ones. They argue the tech sector has an "affirmative obligation to participate in the defense of the nation" and should not shy away from developing technologies, including AI weaponry, required to protect democratic values. This is an unapologetically realist stance, rejecting the perceived luxury of abstention when security is at stake.

Their political corollary follows directly: the software industry must "rebuild its relationship with government" and "redirect its effort and attention to constructing the technology and artificial intelligence capabilities that will address the most pressing challenges that we collectively face"—moving beyond the "smug and complacent focus on shopping websites, photo-sharing apps, and other shallow but wildly lucrative endeavors". To this end, they advocate for "launching a new Manhattan Project" to ensure the United States and its allies retain control over the most advanced AI for defense, warning that "even technical parity with an enemy is insufficient" when facing adversaries unconstrained by ethical considerations.

But the book is not only a policy case; it is also a defense of culture as a condition of building. In a startling, persuasive chapter—“An Aesthetic Point of View”—Karp and Zamiska argue that utility without beauty curdles into design tyranny. Taste is not a luxury; it is orientation toward order. “The abandonment of an aesthetic point of view is lethal to building technology,” they write, because software, like any craft, requires judgment, form, and the courage to prefer. Founder-led companies “outperform,” they note, precisely because an aesthetic point of view creates the space “to pronounce and decide.” Here they are closest to Isaiah Berlin’s tragic pluralism: there is no frictionless harmony of values, so leadership requires bounded choice—Odysseus lashed to the mast so the ship can pass the Sirens.

Theologically, this aesthetic argument returns us to Wojtyła’s center of gravity. If action discloses the person, then culture tutors action—beauty makes truth lovable and freedom livable. When a civilization loses the nerve to distinguish the better from the worse, it also loses the ability to summon its builders to anything higher than optimization. Karp and Zamiska name the cost with admirable bluntness: our “loss of cultural ambition” and the “diminishing demands we place on the technology sector to produce products of enduring and collective value” have ceded too much to the whims of the market.

What, then, is to be done? The authors are not preaching from safe remove. They acknowledge that a “political treatise” from private-sector actors is unusual, then proceed anyway: Palantir, they write, is itself an attempt to blend theory and action through a collective enterprise ordered to public purpose. Their proposed remedy is civic and exacting: recover a national project, recommit the engineering class to the common good, and relearn how to judge—to say “this, not that”—about technologies and the cultures that shape them. The United States has always been a technological republic; “our present advantage,” they warn, “cannot be taken for granted.”

There is urgency here but not despair. Artificial intelligence has concentrated the mind, forcing decisions about identity and purpose that we have deferred for too long. “The moment… to decide who we are and what we aspire to be, as a society and a civilization, is now.” To govern machines, we must first govern ourselves.

That is a political program only because it is first a moral one: belief disciplined into action, freedom yoked to responsibility, beauty recovering the courage to prefer.

If the technological republic is to endure, it must again become a moral republic—one capable of answering what for? as clearly as it answers how fast? ◳