The Homily That Undid an Empire

On June 2, 1979, a philosopher-pope spoke in Warsaw and the world tilted. Karol Wojtyła’s homily restored the human person to history, turning faith into moral resistance. In a single afternoon, words—not weapons—shifted the course of the Cold War.

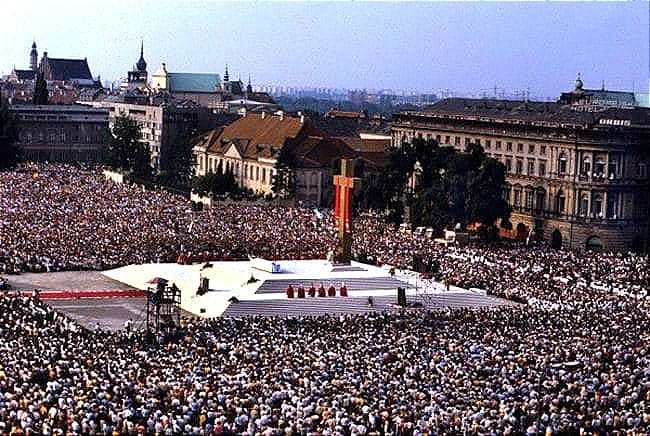

On June 2, 1979, an estimated million people gathered in Warsaw’s Victory Square—the ritual stage of a totalitarian state. The occasion was a papal visit, but the event became something far more profound: a revolution in anthropology.

Before a regime that claimed dominion over the future, Karol Wojtyła—Pope John Paul II—invoked the past, memory, and the essence of humanity. “It is impossible without Christ to understand this nation with its past so full of splendour and also of terrible difficulties.” He declared in his homily. The words were theological on the surface, but beneath lay a radical claim: no human community can endure if it forgets the true nature of the person.

From the crowd erupted an unplanned chant that history remembers: We want God. It was an assertion of existence—a collective refusal to be reduced to mere matter, class, or cogs in a plan. In that moment, the calculus of the Cold War shifted. Power was no longer defined solely by armies or ideology, but by a system's capacity to recognize the inherent dignity of the human being.

In that moment, the calculus of the Cold War shifted. Power was no longer defined solely by armies or ideology, but by a system's capacity to recognize the inherent dignity of the human being.

Wojtyła’s intellectual arsenal was forged long before he donned the white cassock. Born in 1920 in a small Polish town, he came of age under the twin oppressions of Nazism and Soviet communism. He labored in a quarry and chemical factory, performed in clandestine theater, and studied in a secret seminary. From these experiences emerged his philosophical obsession: defending the person against any machinery that sought to exploit or diminish him.

In Love and Responsibility (1960), he articulated the “personalistic norm”: a person must never be treated as a means to an end. In The Acting Person (1969), he posited that each conscious, free act reveals the person and enacts the drama of freedom itself. These were not mere abstractions; they were direct counterarguments to Marxist materialism and, more subtly, to any technocratic vision that reduces individuals to inputs or utilities.

This anthropology addressed the century’s central question: If totalitarianism begins by redefining the human, how can freedom be reborn?

This anthropology addressed the century’s central question: If totalitarianism begins by redefining the human, how can freedom be reborn?

By the time Wojtyła became archbishop of Kraków, he understood that politics flows downstream from culture—and culture from anthropology. His campaign against the communist dogma was a persuasion of conscience, a civilizational fight. The regime rewrote history books; he recited ancient poets (see our previous article on Polish poet Norwid). It nationalized associations; he rebuilt communities. The regime cultivated fear; he formed consciences.

Explore John Paul II’s intellectual connection with the Polish poet Cyprian Norwid in our previous Concordia Discors article.

His nine-day pilgrimage to Poland in 1979 embodied this strategy. He did not directly denounce the Party; instead, he evoked a millennium of Polish memory. He spoke of St. Stanisław, the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier—and through them, of a people’s irreducible moral heritage. “There can be no just Europe without the independence of Poland marked on its map,” he proclaimed before the silent generals arrayed behind him. Each sentence was an act of remembrance against enforced amnesia.

He did not directly denounce the Party; instead, he evoked a millennium of Polish memory.

For nine days, the state’s monopoly on meaning crumbled. Poles realized they were many. Fear—the tyrant’s most efficient tool—was shattered by the simple sight of one another.

For nine days, the state’s monopoly on meaning crumbled. Poles realized they were many. Fear—the tyrant’s most efficient tool—was shattered by the simple sight of one another.

Historians who gauge revolutions by tank divisions still grapple with the epic proportion of what ensued. “When John Paul II kissed the ground at the Warsaw airport,” writes John Lewis Gaddis, “he began the process by which communism in Poland—and ultimately everywhere else in Europe—would come to an end” (The Cold War: A New History, 2005).

Within a year, Gdańsk shipyard workers founded Solidarność (Solidarity)—a movement that translated Wojtyła’s philosophy into civic action: free persons collaborating for the common good. The union’s moral framework echoed The Acting Person: participation without submersion, freedom without radical individualism.

Read more about Solidarność (Solidarity) on Concordia Discors Magazine

The Pope’s alliances with Ronald Reagan and, later, Mikhail Gorbachev extended this anthropology to diplomacy. Both men—one an American actor-turned-statesman, the other an atheist reformer—saw in him a partner who fought not for confessional supremacy but for a transcendent vision of humanity. “The collapse of the Iron Curtain would have been impossible without him,” Gorbachev later conceded.

The Pope’s alliances with Ronald Reagan and, later, Mikhail Gorbachev extended this anthropology to diplomacy. Both men [...] saw in him a partner who fought not for confessional supremacy but for a transcendent vision of humanity.

Totalitarianism fell not to superior propaganda, but to a more compelling definition of the human person.

After 1989, Wojtyła directed his critique westward. In Centesimus Annus (1991), he praised free enterprise but warned that if “capitalism” meant an economy devoid of moral constraints, “the reply is certainly negative.” The new temptation, he argued, was to measure existence by possession—to supplant collectivist materialism with consumerist materialism. The idols had shifted, but the flawed anthropology persisted.

He anticipated what later thinkers like Charles Taylor, Zygmunt Bauman, and Shoshana Zuboff would describe in secular terms: A civilization driven by unchecked desire and data erodes the interior life essential for conscience. Whether imposed by a Party or an algorithm, the dictatorship of matter reduces the person to mere function.

A civilization driven by unchecked desire and data erodes the interior life essential for conscience.

To comprehend the magnitude of Wojtyła’s opposition, recall communism’s lived reality. From 1945 to 1989, Eastern Europe served as a laboratory for social engineering. As Anne Applebaum details in Iron Curtain (2012), entire professions were purged; youth groups and parishes supplanted by state fronts; art and journalism filtered through ideology. Fear infiltrated everyday speech.

The system aimed not just for obedience, conformity, but anthropological transformation—to forge the “new man” of Marxist fantasy. The outcome was the erosion of civic trust. Against this, the 1979 Warsaw homily asserted a timeless truth: The person precedes the system, and any state denying that order is doomed to fail.

Against this, the 1979 Warsaw homily asserted a timeless truth: The person precedes the system, and any state denying that order is doomed to fail.

Why revisit this episode in an era defined not by totalitarianism but by fragmentation and digital code? Because the core question—what is a person?—still underpins freedom.

Today’s idols differ: algorithms predicting preferences, markets quantifying worth, culture wars reducing us to epistemic tribes. Each echoes the old reduction of persons to parts. Wojtyła’s anthropology, secularized, caution us exactly against this drift.

Pluralism cannot survive on procedures alone. It demands a moral ontology—a shared recognition of inherent dignity beyond utility, ideology, or identity. Without it, diversity devolves into relativism, and freedom into mere appetite.

As Karl Popper noted often, the open society relies on citizens who bear responsibility for their individual actions. Such responsibility assumes the self is real, conscience no myth, and meaning no fabricated illusion. The Warsaw homily defended that humanism.

As dusk fell on Victory Square that June evening, Karol Wojtyła raised his voice above the crowd: “Let your Spirit descend and renew the face of the earth, the face of this land.” To believers, it was a prayer; to a watching world, a declaration of moral insurgency. Behind the language of faith lay an anthropology—a vision of man as conscience-bearing, self-determining, irreducible to system or function.

Nine days later, the regime still held the guns, the courts, and the airwaves. But it no longer held the imagination of its people. A decade later, the walls built to contain that imagination crumbled.

What triumphed in Warsaw was the recovery of the human person as the axis of history. Every civilization rises or falls by that measure. When politics forgets it—whether in the name of ideology or efficiency—it rebuilds an architecture of servitude under new names.

Wojtyła’s homily remains a powerful reminder reminder: that freedom begins in anthropology, and that history turns not when power shifts hands, but when a people remembers who they are.