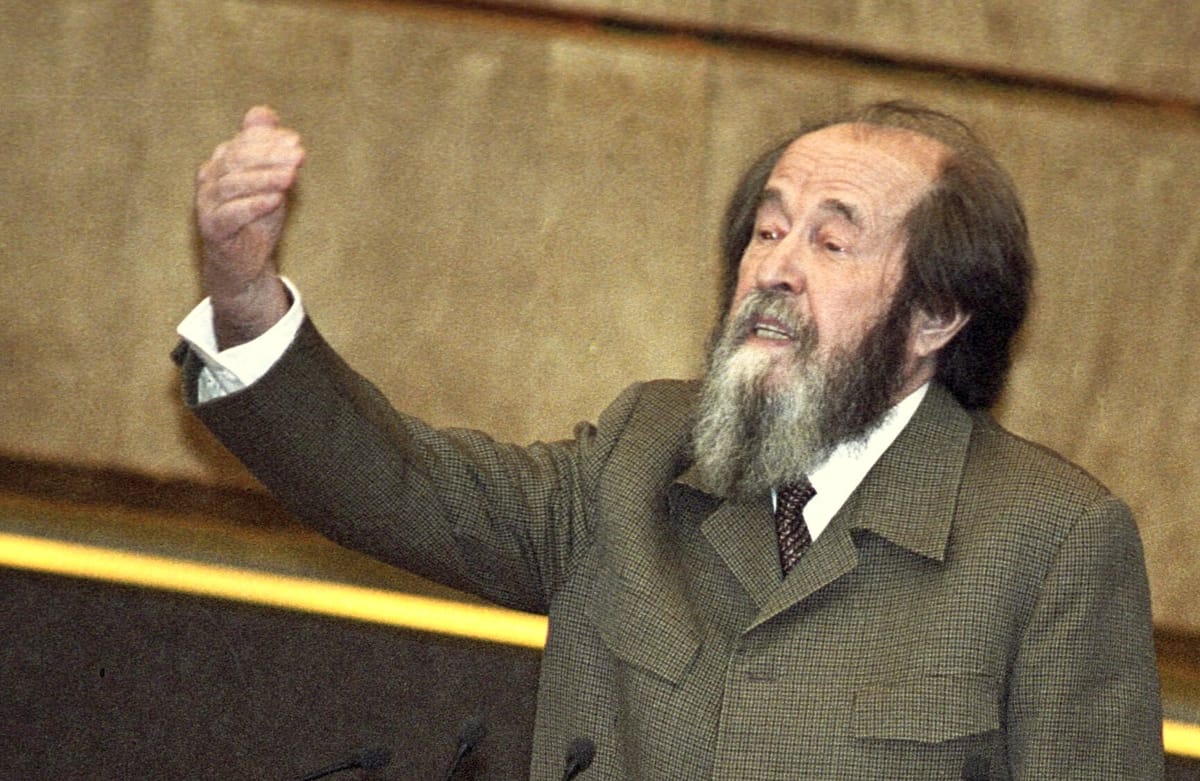

Why Solzhenitsyn’s Moral Courage Is Needed Today

Alexander Solzhenitsyn remains one of the towering moral witnesses of the twentieth century. A soldier, prisoner, writer, and prophet, he lived through the worst that the totalitarian state could inflict, and yet refused to bow his soul to it. What distinguished him was not only his suffering but the clarity with which he named lies as lies and insisted that truth, however fragile, was stronger than the machinery of coercion. Today, in an age far less brutal yet still beset by temptations of conformity, his moral courage speaks to us with renewed urgency.

Solzhenitsyn’s experience of the Gulag taught him that evil thrives on cowardice. Tyranny does not always demand acts of monstrous cruelty from its subjects; it usually requires something simpler—silence, acquiescence, the repetition of slogans we know to be false. His famous injunction, “Live not by lies”, was not a call to armed rebellion but to spiritual steadfastness: to refuse collaboration with falsehood, however small or convenient. In this, Solzhenitsyn revealed that moral courage is not the preserve of heroes alone but a daily responsibility of ordinary citizens.

Our societies today are freer than the Soviet Union of Stalin or Brezhnev, yet they face subtler pressures. The technological age amplifies ideological fashions with astonishing speed. Dissenting voices risk not imprisonment but isolation, loss of livelihood, reputational ruin. In such climates, self-censorship becomes the new orthodoxy, and the temptation to “live by lies”—to repeat words one does not believe, to suppress what one knows to be true—grows ever more powerful. Solzhenitsyn reminds us that once such habits take root, they corrode the foundations of freedom from within.

His courage was never that of a demagogue or a man intoxicated with political power. He rejected utopian illusions, whether Marxist or liberal-technocratic. What he demanded was honesty before God and conscience. This made him a difficult companion for both East and West; yet precisely in this difficulty lay his greatness. He was a man who would not allow himself to be enlisted in service of half-truths, even when they seemed politically expedient. In our present moment—when tribal loyalties, populist passions, and ideological certainties all tempt us to bend truth to faction—this uncompromising stance is indispensable.

Solzhenitsyn also understood that moral courage requires humility. He did not present himself as innocent. In The Gulag Archipelago, he admitted that “the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart.” This recognition is what made his testimony so compelling: it was not a sermon from above but a confession from within. Today, when our public discourse so often descends into moralistic condemnation of others, his reminder that evil is a universal possibility is essential for sustaining pluralism and democratic life.

We need Solzhenitsyn’s moral courage today not because we live under Stalinist terror, but because liberty always depends on the integrity of those who guard it. The battle for truth never ends; it merely changes its terrain. To resist the seductions of falsehood, to speak honestly even when costly, and to remember that each of us is implicated in the struggle between good and evil—these are lessons that no free society can afford to forget.