◳ The UN’s Crisis of Knowing: Karl Popper, Epistemology and Authority

◳ The UN’s future will not be decided by new mandates or bigger budgets, but by whether it can still be trusted to know the world better than anyone else.

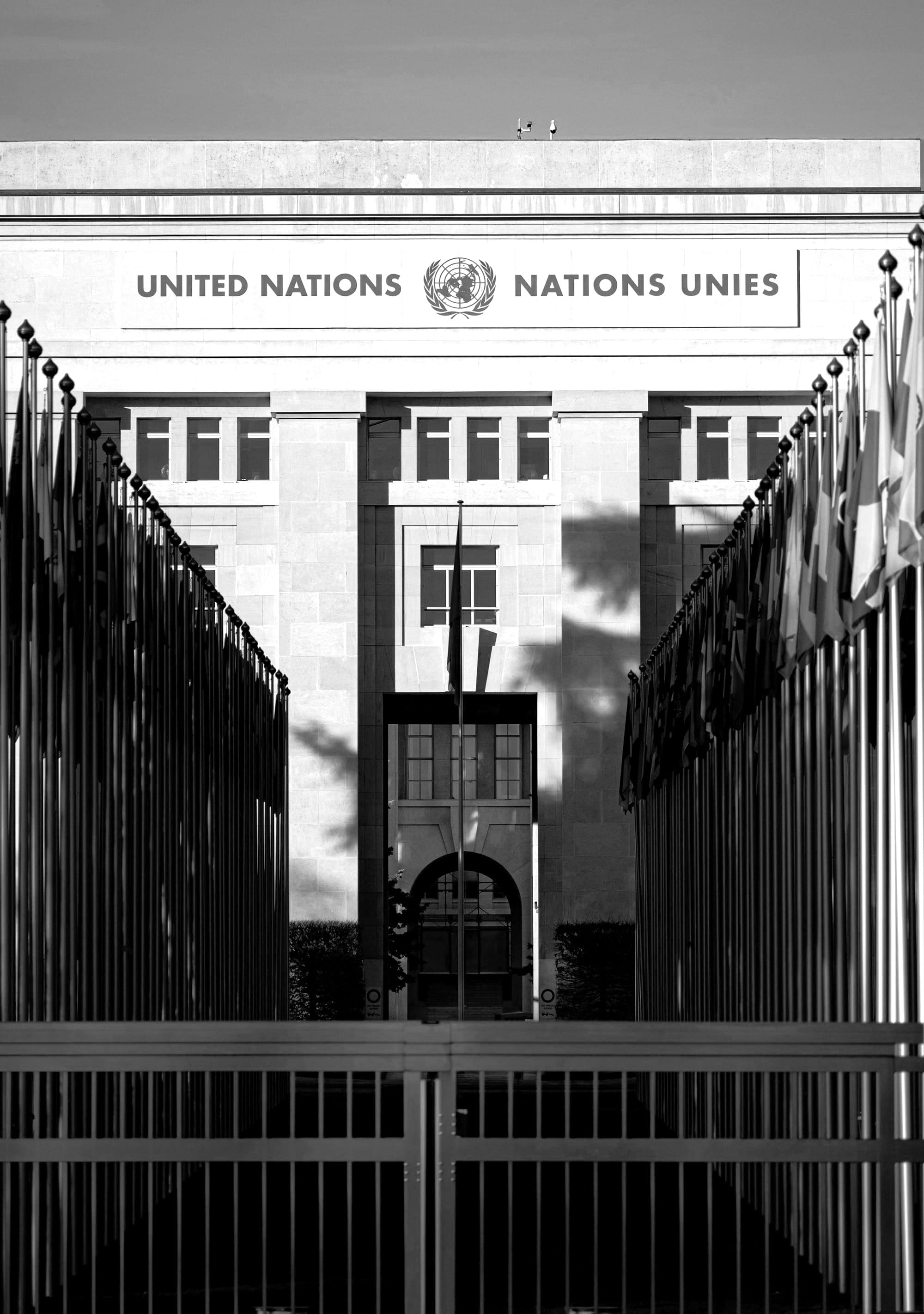

As the United Nations turns 80, the familiar critiques resurface. The Security Council is paralyzed by vetoes; peacekeeping is costly and inconclusive; agencies are sprawling, mandates are overlapping, member states are putting narrow interest above global good, bureaucrats are slow, or similar. No one expects unanimity—or speed—in a chamber of 193 sovereign states, or startup-level efficiency from the mother of all bureaucracy. The UN was never designed for that. Its value lies elsewhere: as the one place where global disputes can be aired, compromises hammered out, and consensus built - and elsewhere should be the target of the long-needed reform.

In an age of intensifying rivalry, there is intrinsic value in keeping adversaries or neighbors talking under a common roof, coordinating, and consolidating. But sustaining that value requires something more basic and less visible: the UN’s ability to know. A General Assembly debate, a Security Council resolution, or a mediation process is only as sound as the information and the trust that underpins it. A Secretary-General, an envoy, or the head of an agency cannot conjure authority from rhetoric or a glorious past alone; their credibility flows from the reliability of the knowledge they bring to the table.

This is the UN’s epistemological problem. Epistemology—the study of how we know what we know—is not a philosophical abstraction here but the foundation of legitimacy. The core business of the UN depends on that, mediation depends on understanding the drivers of conflict; human rights reporting must withstand scrutiny; development programs rest on reliable data and analysis. If the UN cannot provide stronger assurance of reality than states, NGOs, or open-source investigators, why should member states—or the wider public—listen to it?

In short: the UN’s legitimacy rests on its epistemic authority. Without it, condemnations ring hollow, reports read as partial, mediations devolve into theater, and diplomacy becomes performance without substance.

The UN’s convening power rests not on its stage, but on the credibility of the script.

Knowledge as the Foundation of Authority

The UN’s architecture was built not only to host negotiations but also to produce knowledge. The General Assembly fosters deliberation, the Security Council frames urgency, and the Secretariat—together with agencies such as WHO and UNDP—supplies the critical baseline: analysis, data, connections, operations, and reports on which debates rest. This is the “bloodstream of multilateralism,” as former Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld referred to it.

This epistemic role is often overlooked. The UN is frequently treated as if it merely echoes state positions or mechanically follows mandates—but in reality, there is a vast space in between. In practice, trusted information from the Secretariat and its agencies has shaped diplomacy and saved lives. Peace envoys structure mediations on the basis of their teams’ analysis; member states test their views with connected and impartial UN diplomats, development frameworks are negotiated using information collected and contextualized by UN staff; and human rights reporting has proved critical in mobilizing pressure.

This function—providing a baseline of trusted knowledge to all stakeholders of the multilateral system—is what gives the UN’s moral voice force. Strip away the capacity to know and assure information, and the UN becomes only a stage set—grand, but hollow.

From Scarcity to Abundance

Epistemologically speaking, for decades, the UN thrived because information was scarce and fragmented. States held monopolies on data; the UN collated and synthesized, uniquely staffed with an international elite workforce.

That world is gone. Today, X accounts, commercial satellites, smartphones, and networks of open-source analysts create torrents of near-real-time verifiable information. By the time the UN clears and publishes its reports, much of the world has already seen alternative versions. In this new ecosystem, authority is no longer assumed; it must be earned.

The UN once bridged information gaps. Now it must prove it can filter truth from a flood.

The Epistemic Trap

Here lies the crisis. The UN’s political consensus-building is necessary and legitimate. But when that same logic infects its internal knowledge processes, and those meant to support the work of its member states, the result is fragility.

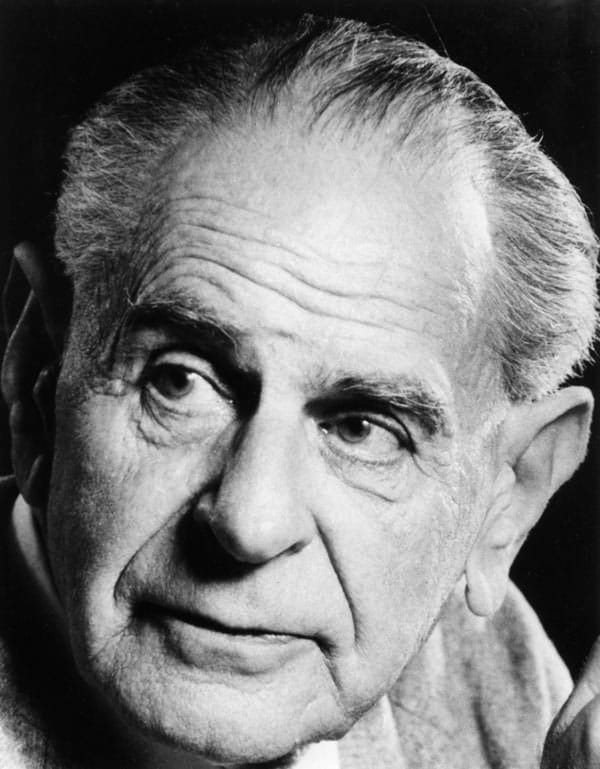

Karl Popper, the 20th-century philosopher of science best known for his theory of falsification, offers a powerful antidote to the UN’s epistemic weaknesses. Too often, the organization operates on verificationism: the instinct to accumulate confirming evidence, smoothing contradictions to preserve consensus. This fosters an environment where flawed assumptions persist, shielded from critique, and where reports or mandates are written so vaguely that they can never really fail.

Too often, the organization operates on verificationism: the instinct to accumulate confirming evidence, smoothing contradictions to preserve consensus.

Popper’s insight was the opposite: knowledge advances not through endless confirmations but by testing claims against evidence that might disprove them. A theory’s strength lies in its survival of attempts to falsify it. As he warned, if no conceivable evidence could refute a claim, it does not speak about reality at all.

Applied to the UN, this means treating policies and reports not as declarations of certainty but as provisional hypotheses. A mission mandate should state the outcomes it expects—and the conditions under which it would be judged ineffective. A development plan should set measurable, falsifiable benchmarks, rather than aspirational goals so broad that success or failure cannot be assessed. Popper also urged piecemeal social engineering over utopianism: testing small, concrete interventions, adjusting when they fail, and building credibility through incremental success, instead of global unverifiable master plans.

By embedding this discipline of doubt—explicit hypotheses, clear criteria, openness to being wrong—the UN could turn its culture from one of justification to one of genuine learning. That is the path to restoring its epistemic authority in a world where credibility is its most valuable asset.

This is how warnings of genocide in Rwanda were sidelined, or why evidence of imminent slaughter in Srebrenica was diluted into neutrality. The result is not just analytical error but a collapse of credibility. If the UN cannot acknowledge uncomfortable truths, why should its reports guide action?

Consensus in the chamber is diplomacy. Consensus in analysis is self-deception.

As an example, open-source intelligence (OSINT) has laid bare this fragility. By prioritizing transparency, replicability, and falsifiability, OSINT communities practice what the UN too often avoids: the critical testing of claims. In a matter of hours, OSINT analysts can geolocate an atrocity, verify a video, or puncture a government denial. They can track trends across conflicts, report on closed-door meetings, and weave the observations of bystanders into a larger, verifiable narrative. This does not make OSINT flawless—it remains vulnerable to manipulation, selective framing, and propaganda. But it has nonetheless reset the standard. Same happens with economic analysis, development projects, and more related to the UN work. In today’s information ecosystem, authority comes not from mandate but from methods that can be independently audited. The UN can no longer rely on the weight of decree; it must earn trust by demonstrating epistemic rigor.

Bureaucracy as a Filter

Inside the UN, the long clearance chains that govern reports and statements are meant to ensure rigor and respect for hierarchy. In practice, they often act as filters for caution. Each layer of review tends to soften language, add qualifications, or strip away uncomfortable facts. What begins as a sharp field assessment is gradually sanded down into diplomatic prose.

This dynamic erodes epistemic clarity in multiple domains. In peace and security, impartiality too easily drifts into false equivalence, as an example presenting local factions as equally responsible—downplaying contextual asymmetries to avoid alienating member states. In development, evaluations of lofty goals often blurred stark failures into vague progress, describing targets as “on track” despite data gaps or stalled outcomes. In humanitarian coordination, the habit of attributing setbacks to “lack of political will” obscures deeper flaws: for example, in some context, internal structures themselves struggled to adapt to non-traditional partners and alternative delivery mechanisms.

These habits do protect one asset: access. By avoiding blunt truths, the UN preserves its role as a facilitator in sensitive environments. But the price is high and it is a trade-off. Every softened report and evasive formulation chips away at its epistemic authority. The organization may remain welcome in the room, yet it ceases to be the trusted guide others look to for a clear picture of reality.

Why Knowledge Is the Bedrock of Legitimacy

Every core UN function—mediation, development, human rights, humanitarian action—depends on trusted knowledge. An envoy cannot truly mediate with faulty analysis, with partial views, with incomplete trends. A development plan collapses without reliable data. Human rights findings lose force if they cannot withstand scrutiny.

This is why the epistemic crisis is existential. Without credibility in knowing, the UN’s other roles unravel. Condemnations, good offices and speeches ring hollow if not grounded in shared truths.

Reform: Restoring Epistemic Authority

What is needed is not just new tools, but a shift in mindset—toward transparency, accountability, and intellectual humility.

- Transparency: Publish organizational charts and workstreams so it is clear who is responsible for what, reducing opacity and enabling external scrutiny.

- Red Teaming: Create protected forums where staff can rigorously challenge consensus narratives without fear of retaliation or career harm.

- Explicit Assumptions: Require reports to spell out the assumptions behind their analysis and specify the conditions under which those assumptions would no longer hold.

- Streamlined Clearance: Deploy AI to speed up bureaucratic reviews, reducing delays and allowing diplomats to focus on substance rather than process.

- Culture of Humility: Train leaders to see correction and falsification not as threats to authority but as demonstrations of institutional strength.

Hammarskjöld’s Reminder

Dag Hammarskjöld envisioned an international civil service independent enough to rise above national narratives. For him, knowledge was not a neutral commodity but the basis of preventive diplomacy. His vision is a reminder: the UN’s purpose is not just to host debates but to ground them in truth.

The UN survives not by echoing states, but by clarifying reality.

Legitimacy Through Knowing

Consensus in debate is the UN’s nature. But consensus, or hierarchical pushes in analysis is its undoing. Without epistemic authority—without the ability to know and to demonstrate knowing—the UN’s legitimacy evaporates. It becomes not the guide, or the bloodstream of multilateralism but its stage set.

To remain relevant in the digital age, the UN must reclaim its authority through rigor: testing assumptions, welcoming falsification, integrating new streams of knowledge, and protecting the independence of its analysts. Only then can it continue to provide the trusted baseline upon which peace, rights, and development depend. ◳

The UN will endure not because it hosts debates, but because it anchors them in a higher degree of truth.