◳ The Soul of Poland in Music

Chopin called it żal—a sorrow that smiles through tears. From mazurkas to Paderewski’s anthems, Polish music became a form of sovereignty: beauty transfigured by suffering, melody as the nation’s survival.

In 1921, a forgotten author in an American music magazine attempted to answer a question that lingers still: why has Poland produced so much great music? Reminding us that culture can preserve a nation.

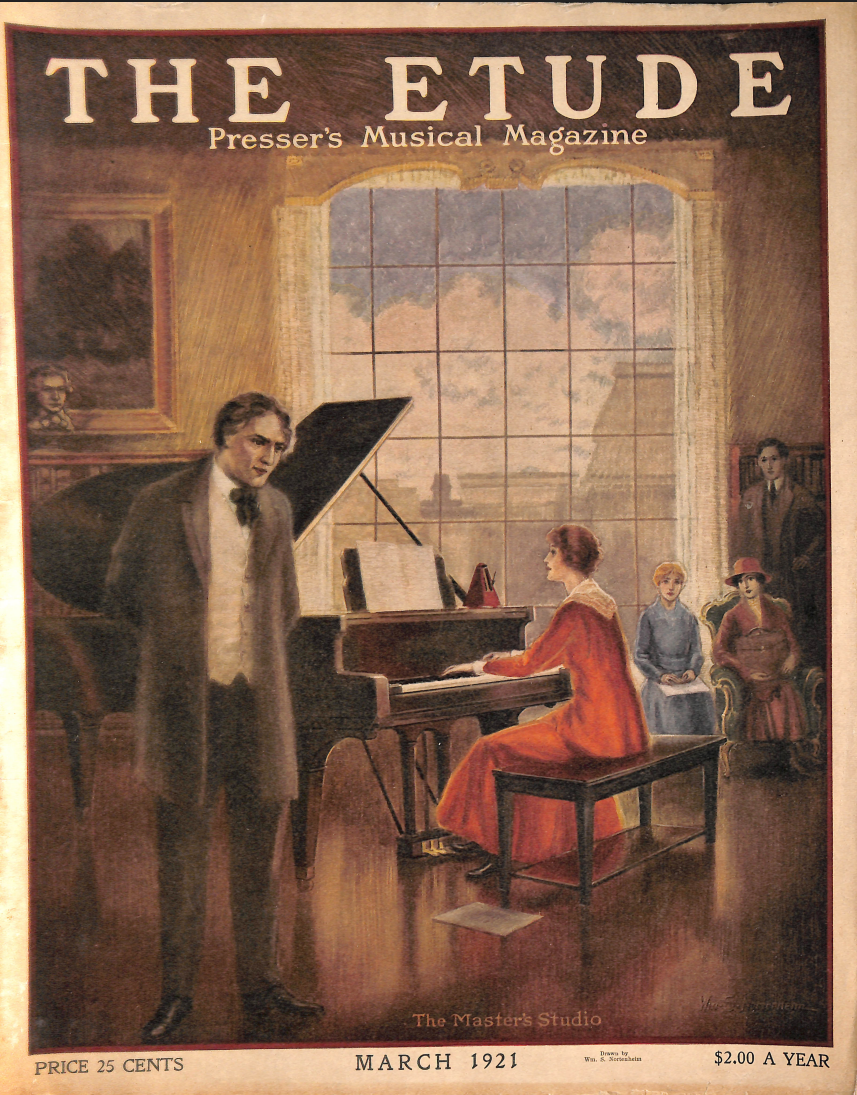

We know almost nothing about Michael J. Piduch—his name appears in no standard bibliographies, and no reliable references to his life survive. What we do know is that in March 1921 he published in The Etude magazine a short yet ambitious essay, The Soul of Poland in Music. In its way, the piece is a forgotten jewel: an American contribution, tucked into a popular music periodical, that dares to grapple with a question at once obvious and unanswerable—what is the soul of Poland in music?

Piduch begins with an admission of difficulty:

“Polish music in general is like a kaleidoscope – so varied in color and tenseness that it seems almost impossible to acquire one definite, clear and comprehensive idea of it. Much less is it possible to discuss the subject per longum et latum in a few passing paragraphs. Therefore out of moral and physical necessity I shall limit myself to the sole consideration of – why Polish music is what it is.”

This humility sets the tone. The subject is vast, but he wants to find its essence. He quickly moves to psychology: music, he writes, “belongs to the most subtle and most sensitive organs of the soul,” and is shaped by environment and history. Just as we can distinguish a French court ballad from a Brazilian maxixe, so too can we recognize the character of a nation in its music.

Piduch’s central claim is bold:

“Music expresses, more than does literature, the soul of a nation. A typical case of this truth is the music of Poland. Polish music expresses the soul of Poland more than the deep, mystical and inspiring words of Adam Mickiewicz.”

This is no small statement. Mickiewicz, Poland’s great Romantic poet, was the prophet of exile. Yet Piduch argues that Chopin’s mazurkas and Paderewski’s polonaises tell us more. Each folksong, each melody, he writes, breathes “a different spirit,” overwhelming the listener with moods until the mind is “awhirl with that certain, unexplainable feeling of pleasurable pain.”

“On hearing a typical Polish melody, I recall that I smiled even through oncoming tears.”

This “sweet melancholy” is central. It is an emotion at once joyful and sorrowful, and for Piduch, its name is żal.

To explain this mysterious word, Piduch turns to a story rich with the atmosphere of Parisian Romanticism, recounted by Franz Liszt in his romanticized Life of Chopin. He describes the French noblewomen Countess d’Agoult asking Chopin what secret essence he sealed within his compositions, which she likened to “superb urns of most exquisitely chiseled alabaster” holding “unknown ashes.” Her question was as poetic as the music itself, suggesting that his perfect forms contained something sacred, perhaps unknowable, at their core. Chopin offered no grand theory. Instead, he answered with a single Polish word that landed with the weight of history: żal. As Liszt tells it, Chopin repeated the word “again and again,” testing the contours of a feeling no other language could fully contain.

Chopin offered no grand theory. Instead, he answered with a single Polish word that landed with the weight of history: żal.

This anecdote shows the central nerve of Polish music. Żal was the "unknown ash" in Chopin’s urns—an untranslatable emotion fusing profound sorrow with stubborn pride, tender longing with the bitterness of revolt. Piduch argues this was not just Chopin’s secret, but the unifying soul of his nation's art, a resonant frequency echoing through the centuries from the Renaissance psalms of Mikołaj Gomółka to the modern anthems of Ignacy Jan Paderewski.

Piduch cites The Etude’s previous work, where the word żal had been introduced to American readers: “Strange substantive, embracing a strange diversity and a strange philosophy!” He expands on that strangeness: żal can mean humility and resignation before Providence, but also rancor, revolt, “menace never ceasing to threaten.” It is not a mild sadness, but a spectrum from tenderness to vengeance.

What created this strange philosophy? Piduch answers: “History and nature have been the strange hands that molded this wonderful spirit.”

History first. He reminds his readers that music often arises as “the ‘bitter’ sweetness distilled from suffering and privation.” No country, he quotes Leopold Stokowski from The Etude’s 1915 issue, “has been more torn and crushed in the political grinding together of powerful and warring neighbors than Poland.” From Tartar invasions to Teutonic Knights, from Vienna to Tannenberg, Poland has fought and bled for Europe. He recalls Henryk Sienkiewicz’s phrase, “In the spring the hordes will come,” and the tragic partitions described by Alison as combining “all the meanness of political swindling, the fury of national rapine and all the atrocity of military massacre.”

And then nature. Piduch describes the Polish landscape as “monotonous, but beautifully monotonous,” with vast plains stretching to misty horizons. Over this quiet beauty hovers “a spirit of mystery, unrest, a spirit of unexplainable sadness, loneliness and sweetest melancholy.” He evokes the silence of shepherds’ flutes at night, the dreamy calm of summer evenings, and the sudden reminder that “happiness is not the sole goal of thy frail life… Vanity of vanities; all is vanity.”

“The beauty of Poland is monotonous, but beautifully monotonous. It breathes sweetness, delight, cheer, content, all crowned with this mysterious and unintelligible spirit of melancholy, this untranslatable – ŻAL!”

The effect is lyrical, almost mystical. He sounds less like a critic than a witness.

Exile, too, became part of this musical philosophy. Chopin wrote his mazurkas and polonaises in Paris, far from Warsaw, yet infused them with rhythms and cadences that carried the memory of his homeland. Paderewski, decades later, would tour America, raising funds for independence with the same music. In Piduch’s terms, żal was not confined to the Polish plains; it was exportable sorrow, able to transform foreign concert halls into temporary homelands. This portability of feeling helped Poland endure: music became the nation’s passport when no other document sufficed.

Piduch concludes with both pride and sorrow. Poland, “baptized in fire and surrounded with the sweet melancholy of Nature, gave birth to a music of a strange philosophy.” Out of centuries of wounds came dances of world fame—the Polonaise, Oberek, Kujawiak, Krakowiak, Mazurka. Foreign composers tried their hand at these dances, he notes, but produced only imitations: “Tempo di Polacca.” The real thing was untranslatable. Piduch’s essay also leans, often implicitly, on a spiritual register.

He writes of resignation “before the fiat of necessity and the inscrutable decrees of Providence,” echoing a long tradition in which Polish music was heard as prayer as much as art. From Gomółka’s psalms to the sacred undertones of Chopin’s preludes, from Paderewski’s hymns to later twentieth-century laments, the language of faith infused the language of sound. This spiritual dimension helps explain why Polish music could bear so much historical weight: it was not only aesthetic but sacramental, offering meaning where history seemed senseless.

Reading Piduch today, we are struck by his insistence that culture comes first. Poland in 1921 was newly independent, resurrected after more than a century of partitions. But the groundwork had long been laid in music. Chopin’s mazurkas carried the nation when the state did not exist. Żal became a form of sovereignty when political sovereignty was denied.

Piduch reminds us that culture is survival. Nations live in their melodies when they cannot live in their borders. And the strange philosophy of żal was the motif through which Poland endured. “Art, and particularly music, nurtured in the breasts suffering all this, could not possibly have been different.”

Poland in music is not only beauty, but beauty transfigured by suffering; not only melancholy, but melancholy that resists despair. That is żal.

Michael J. Piduch has vanished from history. But his words, nestled in a magazine that promised its readers scales and sonatas, leave us with a truth: the soul of Poland in music is not only beauty, but beauty transfigured by suffering; not only melancholy, but melancholy that resists despair. That is żal. And that is why Polish music remains, a century later, not just art, but a form of cultural sovereignty — the song of identity and hope. ◳

👉 You can browse the full digital archive of The Etude magazine here—it’s a fascinating resource. The March 1921 issue includes The Soul of Poland in Music by Michael J. Piduch.