The Solitude of the Hearts. Tocqueville, Weil, and the Roots of Polarization

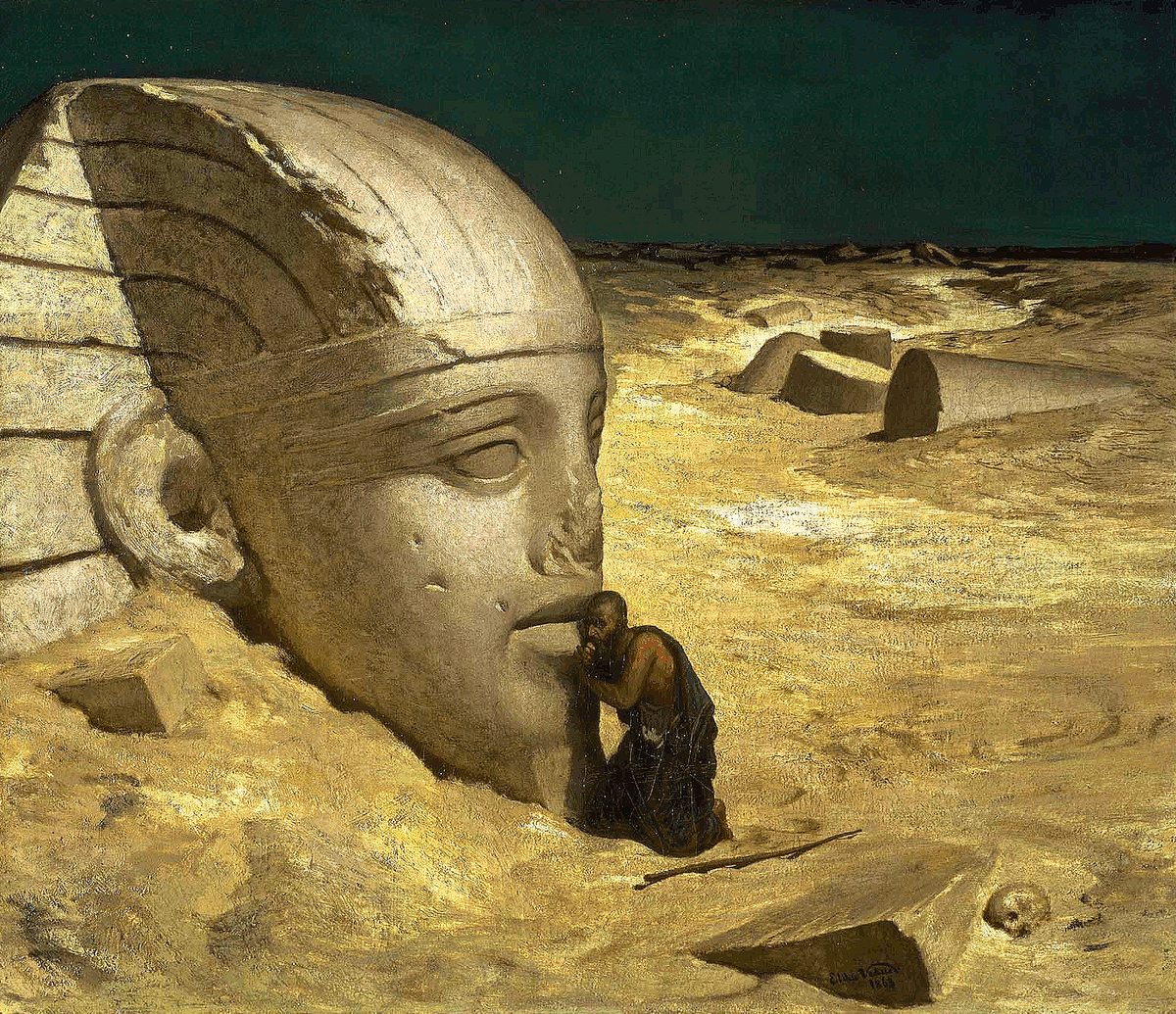

Amid rising loneliness and moral fragmentation, Tocqueville’s “solitude of the hearts” and Weil’s “uprootedness” expose the deeper crisis beneath polarization: a humanity searching for belonging where its roots have thinned — yet still capable of replanting them in shared meaning and care.

“They owe nothing to any man, they expect nothing from any man; they acquire the habit of always considering themselves as standing alone, and they are apt to imagine that their whole destiny is in their own hands. Thus not only does democracy make every man forget his ancestors, but it hides his descendants, and separates his contemporaries from him; it throws him back forever upon himself alone, and threatens in the end to confine him entirely within the solitude of his own heart.”

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Vol. II, Ch. II: “Of Individualism in Democratic Countries” (1840)

Across conferences, journals, and boardrooms, the study of polarization has become the moral inquiry of our age. Scholars trace its origins to technology, inequality, education, or media; psychologists point to cognitive bias and moral outrage; economists to class and geography. Each analysis adds a new piece to a complex puzzle. Yet beyond these proximate causes lies a deeper, quieter diagnosis: a fracture of belonging.

For all our sophistication, we remain haunted by what Alexis de Tocqueville called the solitude of the hearts—that spiritual withdrawal into the self which, in his view, was democracy’s most subtle danger. Nearly a century later, Simone Weil would give that condition another name: uprootedness (déracinement). To be uprooted, she argued, is to live separated from the traditions, culture, and community that provide vital nourishment for the soul. (The Need for Roots, 1949). Tocqueville saw solitude; Weil saw exile. Both discerned the same moral void.

Tocqueville saw solitude; Weil saw exile. Both discerned the same moral void.

Their warning resonates powerfully today. Amid unprecedented freedom and connectivity, we are lonelier, angrier, and more fragmented than generations who endured war or tyranny. The quarrel has migrated inward. What divides us is not only what we believe, but how we belong.

Empirical studies make the moral intuition plain. In 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General declared loneliness a national epidemic, noting that Americans appear to be becoming less socially connected in the past two decades, adding that social isolation increases the risk of premature death by nearly 30%—“as harmful as smoking fifteen cigarettes a day” (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation, HHS, 2023).

Social surveys paint a stark picture. The share of Americans who say "most people can be trusted" has fallen to a record low of 31%, down from nearly half a generation ago (General Social Survey). Church membership has fallen below 50% for the first time in recorded history (Gallup, 2021). And in a 2021 Survey Center on American Life study, the proportion of Americans reporting no close friends has quadrupled since 1990.

The civic consequences are visible. Pew Research Center data show that the share of Americans holding “very unfavorable” views of the opposing party has risen from 16% in 1994 to 63% in 2022. Yet the problem is less partisan rage than moral displacement. As Robert Putnam observed in Bowling Alone (2000), when social capital declines, politics tends to become a struggle for identity rather than for policy.

Polarization is not simply a clash of ideologies; it is a symptom of isolation.

Polarization is not simply a clash of ideologies; it is a symptom of isolation. The solitary heart, deprived of natural bonds, seeks attachment—and finds in politics one of the few socially acceptable ways to feel part of something larger.

Tocqueville foresaw this path. In Democracy in America (1840), he praised the moral energy of civic associations—what he called “free schools” where citizens learned to cooperate beyond private interest. Yet he also warned of a creeping solitude unique to democratic life, fearing a soft despotism under which each person would become:

“...a stranger to the fate of all the rest; his children and his private friends constitute to him the whole of mankind. As for the rest of his fellow citizens, he is close to them, but he does not see them; he touches them, but he does not feel them; he exists only in himself and for himself alone...”

Equality, Tocqueville believed, liberates but also isolates. As traditional hierarchies vanish, individuals are left alone with their choices, their anxieties, and their appetites. The great danger of the democratic age, he warned, was that man would drift apart and lose sight of one another.

The great danger of the democratic age, he warned, was that man would drift apart and lose sight of one another.

That warning has become prophecy. In the digital age, technology promises intimacy while delivering abstraction. The average person now spends many hours each day on phones or screens, yet reports fewer close friendships and weaker community ties. The paradox of connectivity is that it multiplies contact while hollowing relation.

Politics, in this world, becomes therapy. As the ordinary bonds of family, faith, and place erode, individuals turn to ideological commitment to fill the void once occupied by vocation and belonging. What Max Weber called the Beruf — the sense of work as a calling, a meaningful contribution to the world — has withered under the pressures of mobility, secularization, and technocratic efficiency. In its absence, politics offers itself as a surrogate vocation: a stage on which the self can feel morally significant again.

[...] politics offers itself as a surrogate vocation: a stage on which the self can feel morally significant again.

Sociologists have described this drift as a “sacralization of politics” (Emilio Gentile, Politics as Religion, 2006), in which the emotional energies once directed toward religion or communal duty are redirected toward political identity. The result is moral inflation: politics must now provide not only governance but grace, not only policy but purpose. Politics in this context promises an ersatz redemption through collective struggle — a sense of transcendence in an age that no longer believes in transcendence.

Politics in this context promises an ersatz redemption through collective struggle — a sense of transcendence in an age that no longer believes in transcendence.

The greatest analyst of totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt saw the danger of this substitution early on. In The Human Condition (1958), she warned that when private life no longer offers meaning, the public sphere becomes overloaded with existential demand. She argued that the purpose of citizenship is not to find personal salvation but to act together in a shared world. Yet in the vacuum left by other forms of attachment, politics ceases to be a shared practice and becomes a form of self-expression—a therapeutic confession broadcast to the crowd. In this sense, our polarization is not merely ideological but also spiritual. Politics has become, for many, the last remaining language of moral seriousness — the place where the longing for vocation disguises itself as opinion.

Politics has become, for many, the last remaining language of moral seriousness — the place where the longing for vocation disguises itself as opinion.

Simone Weil grasped this transformation with prophetic clarity. Writing amid the evils and exiles of the Second World War, she identified uprootedness as the defining spiritual condition of the modern world. “To be rooted,” she wrote, “is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul”.

Roots, for Weil, were not ethnic or tribal, or even cultural in its strict sense. They were moral—a “real, active and natural participation in the life of a community” that preserves the "treasures of the past and... expectations for the future". When these living connections are severed, she warned, the uprooted seek false attachments. The malady, she argued, is a "self-propagating one". Those afflicted either "fall into a spiritual lethargy resembling death" or are driven to "hurl themselves into some form of activity necessarily designed to uproot... others". Her diagnosis was blunt: "Whoever is uprooted himself uproots others. Whoever is rooted himself doesn’t uproot others".

The resonance with today’s polarization is unmistakable. Uprooted citizens, cut off from enduring sources of meaning, turn to ideology as a surrogate faith. Political tribes function as parishes of belonging, moral absolutes replace shared reality, and disagreement becomes heresy. The human need for connection, unmet, is transmuted into moral combat.

Uprooted citizens, cut off from enduring sources of meaning, turn to ideology as a surrogate faith. [...] The human need for connection, unmet, is transmuted into moral combat.

Human history has endured deeper and more divisive conflicts than today—world wars, revolutions, civil strife. So, why, then, does today’s polarization feel uniquely intimate and exhausting?

So, why, then, does today’s polarization feel uniquely intimate and exhausting? The answer lies not in the scale of disagreement but in the fragility of the self.

The answer lies not in the scale of disagreement but in the fragility of the self. Earlier societies, for all their violence, rested on thick networks of belonging: family, congregation, regiment, guild.

These provided continuity and recovery. Modern life, by contrast, prizes mobility, expression, and autonomy—virtues that, detached from communal structure, become liabilities. Freedom, unaccompanied by rootedness, breeds anxiety. And anxious individuals cling. They cling to movements, screens, or slogans that promise certainty. The algorithmic marketplace amplifies this tendency. Studies by Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge show that rates of adolescent anxiety and depression soared after 2012—the year social media became mobile and algorithmically personalized (The Anxious Generation, 2024). Digital life, designed to reward outrage, gives solitude the illusion of participation.

Thus, polarization today is not merely ideological, or induced by policies or technology; it is existential. It satisfies the longing for belonging in a rootless age.

Thus, polarization today is not merely ideological, or induced by policies or technology; it is existential. It satisfies the longing for belonging in a rootless age.

But Tocqueville and Weil do not leave us with diagnosis alone; they point toward a path of repair. They converge on one truth: freedom requires form.

Tocqueville’s solution was associational. He found this form in the “little republics” of civic life—the voluntary associations where citizens, by acting together, practiced the habits of trust. Weil’s solution was attentional. She located it in the spiritual discipline of seeing the other as an end, not a means. Both saw that liberty and rootedness are not opposites but partners.

Herein lies the true task of depolarization. Efforts must move beyond civility campaigns and fact-checking; they must be a work of re-rooting.

Herein lies the true task of depolarization. Efforts must move beyond civility campaigns and fact-checking; they must be a work of re-rooting. The solution is to rebuild the moral architecture of belonging: the families, schools, associations, and shared rituals that train citizens to see one another not as abstract symbols but as concrete neighbors. As David Brooks argued in his 2019 book, The Second Mountain, the path of repair requires a fundamental shift from a culture of autonomy to a culture of commitment.

Beneath all the statistics lies a simpler narrative: a lonely species, wired for communion, has built systems that monetize disconnection. The solitude of the hearts is not just a private sorrow; it is a civic wound. When people no longer trust, societies no longer cohere. Democracy depends not only on votes but on the invisible ties of empathy and shared fate.

The solitude of the hearts is not just a private sorrow; it is a civic wound.

This helps explain why our polarization, though bloodless, feels civilizational. It is not the clash of two halves of a nation but the implosion of the whole into isolated moral worlds. Tocqueville foresaw this psychological atomization; Weil diagnosed its metaphysical cause. Both understood that politics becomes pathological when it tries to replace the human need for rootedness.

No single policy can mend the solitude of the hearts, but the direction is discernible. Tocqueville’s remedy was civic participation — those small, voluntary spaces where individuals learn competence, reciprocity, and restraint. Weil’s was spiritual attention — the discipline of perceiving others without possession, of seeing rather than using. Both begin in humility: the recognition that we belong to more than ourselves, that the common world precedes and sustains the self.

Renewal, in this sense, is a remembering. It means building institutions and technologies that privilege continuity over novelty, depth over reach. It means reimagining education as the transmission of gratitude rather than information — a training of perception, not merely of skill. It means recovering civic rituals — festivals, neighborhood councils, shared meals — that turn proximity into fellowship and strangers into citizens.

Both Tocqueville and Weil died young, haunted by the same premonition: that democracy, left to its appetites, might forget its soul. Tocqueville, consumed by illness, still dictated reflections on liberty’s moral foundations; Weil, in chosen deprivation, sought solidarity with the afflicted. Each, in a different register, testified that the strength of a society begins in the interior life of its members.

Each, in a different register, testified that the strength of a society begins in the interior life of its members.

Freedom, they remind us, is not secured by prosperity or rights alone but by relation — by the steady effort to see, to serve, and to stay. The solitude of the hearts and the uprootedness of the soul are the invisible architecture of polarization: they drive citizens to cling to false attachments because true ones have withered.

The solitude of the hearts and the uprootedness of the soul are the invisible architecture of polarization: they drive citizens to cling to false attachments because true ones have withered.

If the nineteenth century discovered equality and the twentieth pursued emancipation, the twenty-first must rediscover belonging — not as sentimentality, but as necessity. The task before us is not to perfect freedom, but to re-root it: to bind liberty once more to love, and to remember that a democracy of uprooted hearts cannot endure. ◳

The task before us is not to perfect freedom, but to re-root it: to bind liberty once more to love, and to remember that a democracy of uprooted hearts cannot endure.

Related Reflections from Concordia Discors Magazine

This Week in Concordia Discors Magazine