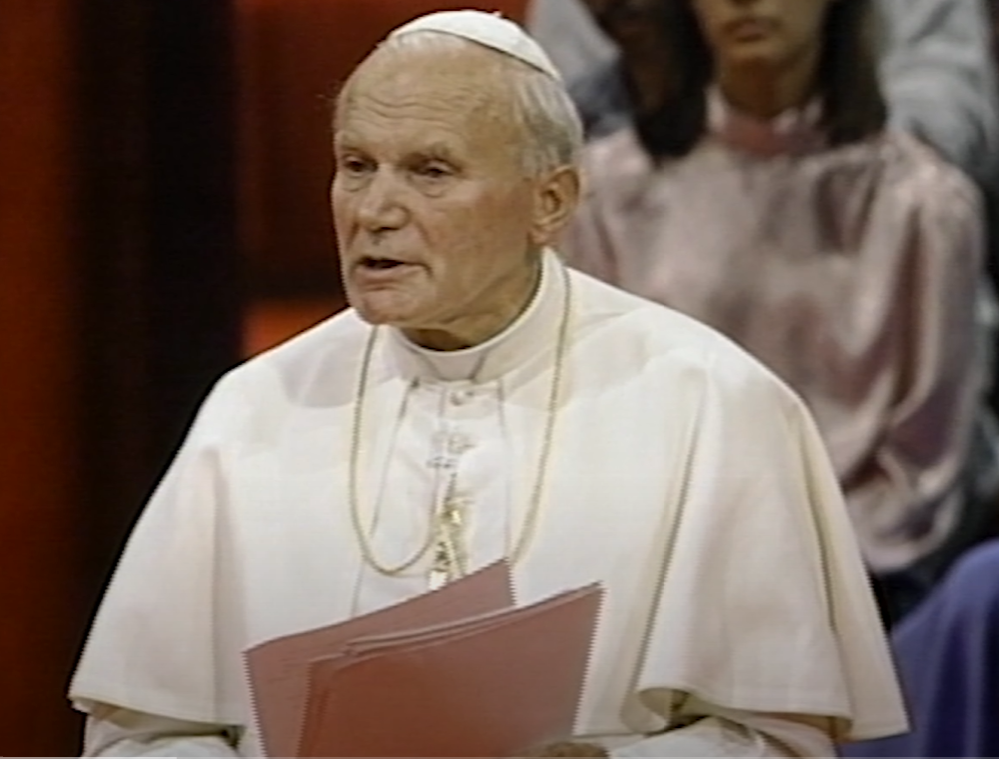

The Poet Pope: Karol Wojtyła

How a young Pole—orphan, laborer, actor, priest—armed his conscience with verse and learned to defend human freedom from Nazism, Communism, and our age of noise.

In brutal times it is easy to think culture is a luxury. Karol Wojtyła (1920–2005) knew better. Before he became John Paul II, he learned—under the brown boot of Nazism and the red fist of communism—that poetry, theater, and prayer are not ornaments but armor. They keep a name alive when regimes issue numbers. They preserve the inner voice when propaganda shouts. His poems, many written under the pseudonym Andrzej Jawień, are the laboratory where he formed a conscience capable of resisting totalitarian simplifications. Read them and you meet not a marble saint but a man: son and orphan, quarry worker and student, actor and hiker, priest and friend—someone who fought for freedom.

Forged in loss: mother, brother, father

The roots are raw. Wojtyła’s mother died when he was eight; his brother, a young doctor, when Karol was twelve; his father—his austere companion and model of prayer—during the war in 1941. That loneliness did not shrink him; it drove him deeper. It is why mothers and fathers haunt his poetry, and why the ordinary—bread, water, stone, rings—becomes luminous. In his verse the family is neither ideology nor sentimentality; it is the first school of dignity.

“I knew—the light that lingered in ordinary things,

like a spark sheltered under the skin of our days—

the light was You; it did not come from me.”

—from “The Mother” cycle (1950)

Culture as resistance: theater and the quarry

Under Nazi occupation in Kraków, university life was shuttered and culture targeted for erasure. By day Wojtyła labored at a quarry and chemical plant; by night he joined friends in the clandestine Rhapsodic Theater, where spoken word—not sets or costumes—carried a people’s memory. The practice shaped a poetics of essence: spare, idea-centered, resistant to spectacle. Totalitarianism thrives by noise and forgetting; the spoken word, carefully tended, remembers.

“The hammer pounds the rock; dust rises, choking the air.

The hands grow raw, but in the stone’s resistance something endures—

a shape, a meaning—hidden in fragments at our feet…

The greatness of work is inside man.”

—from “The Quarry” (1956)

That conviction—work discloses the worker—would echo later in his social teaching. It also answers both tyrannies: Nazism that dehumanized by race, communism that instrumentalized by class.

Between Romantics and Thomists: the mind he built

After the war, with Stalinist pressure intensifying, he studied in a secret seminary while writing poetry and drama. He loved Poland’s Romantics (Mickiewicz, Norwid) for their moral seriousness, yet his lines are clarified by St. Thomas Aquinas and enriched by phenomenology: truth is something we receive in encounter, not manufacture to suit a party line. That anthropology—person over system, conscience over decree—animates his most enduring poems.

“Thought is a strange space.

It opens within us, and yet it leads beyond us.

Conscience enters here, hearing a word not its own.”

—“Thought Is a Strange Space” (1952)

Poems that hold a people together

1) Song of the Hidden God (1944): Faith in the ruins

Written amid the terror of occupied Kraków, it is a prayer with cracked lips:

“You are the One who is, who has always been.

You hide Yourself in the darkness of human suffering.

My whole being reaches for You like a root in dry soil,

thirsting for a drop of hidden rain.”

This is not denial of evil; it is refusal to let evil define the last word.

2) Song of the Brightness of Water (1950): Truth as encounter

Under “Jawień,” he imagines the Samaritan woman—a drama of thirst meeting Truth:

“The well sparkles with leaves that leap to your eyes…

Multitudes tremble in you,

transfixed by the light of His words as eyes by the brightness of water.”

Against ideologies—Nazi myth, Marxist dogma—he proposes a meeting of persons, where freedom matures.

3) Profiles of the Cyrenean (1957): The self under burden

Pressed into carrying another’s cross, Simon discovers himself:

“They forced him to take the wood. He did not want it,

but it lay on his shoulders.

Yet in that hour he became more himself than ever before.”

For a nation enduring conscription to alien projects, the poem names a sober hope: unwanted suffering can still be turned into gift.

4) The Jeweler’s Shop (1960): Fidelity as freedom

A verse-drama on marriage, it treats rings not as adornments but vows that shape souls:

“The weight of these rings is not the metal,

but the measure of man and woman,

each entrusted to the other,

each tested in the fire of years.”

Here the person resists both commodified passion and statist intrusion. Covenants make liberty durable.

5) Easter Vigil (1966): The person greater than history

For the millennium of Polish Christianity, he lifts persons above historicist cages:

“Each man in history loses his body and goes toward You.

In the moment of departure each is greater than history.”

Communism claimed to own history’s direction; Wojtyła returns judgment to the human face.

6) Song of the Earth: Creation revealing Love

Neither romantic escape nor socialist utility, nature is a partner in meaning:

“Listen: electric current cuts through a river of rock—

and thought grows in me day after day.

The earth bears hidden energies; we meet them with our hands.”

The land forms culture not by force but by gift—received, cultivated, praised.

7) Roman Triptych (2003): The elder’s benediction

At the end of his life he revisits mountain streams and the Book of Genesis:

“The undulating wood slopes down to the rhythm of mountain streams.

To me this rhythm reveals You—the Primordial Word.

If you want to find the source, you must go up, against the current.”

The arc closes: from the wartime “Hidden God” to the contemplative “Primordial Word.” The answer, always, is to go upstream—to the source of truth, not the slogans of the day.

Against Nazism and communism—without becoming propaganda

Wojtyła never wrote agitprop. He did something harder: he remembered. Under the Nazis, memory was resistance—reciting poems by heart in private rooms while friends disappeared. Under the communists, reality was resistance—naming what is, not what the Party decrees. His poems teach a grammar of freedom:

- The person is irreducible. No race theory or class dialectic can exhaust a human face.

- Work reveals dignity. The worker is not a tool of the state; the meaning of work is inside the worker.

- Truth is received in encounter. It is not invented by slogans or secured by censorship.

- Fidelity anchors freedom. Vows—parental, marital, priestly—stabilize love against manipulation.

- Hope outlasts terror. Even when God is hidden, the heart keeps reaching.

This grammar later animated his public witness. In 1979, preaching in Warsaw, he did not call for insurrection; he called his people to remember who they were and “do not be afraid.” It was the poet speaking—one who had spent decades training attention to reality and encouraging others to do the same. Solidarity did the rest.

The role of the mother—and the memory that heals

Because he lost his own mother early, motherhood in his poems is awe before mystery, not sentiment. He refuses the modern temptation to treat children as extensions of adult projects. The mother in Wojtyła listens and receives:

“I knew…the light in ordinary things was You.”

That line is powerful. It sanctifies the daily and consecrates the weak. It also rebukes the eugenic and utilitarian impulses of both regimes he faced—one obsessed with racial “purity,” the other with productive value. In his poetics, the smallest is luminous.

A man who hiked, worked, prayed—and wrote

It matters that he hiked the Tatras, that he laughed with students in kayaks, that he read philosophy at night after shifts in the dust. The poems are credible because the poet lived them. He was not shielding himself from history; he was walking through it—and insisting that the soul can remain free inside it. That is why the voice in these lines is steady, never shrill: he learned that beauty persuades where force only exhausts.

Why we need his poetry now

Our age is not occupied by troops but by distractions. We outsource conviction to tribes and allow algorithms to curate our attention. Wojtyła’s poems are a counter-technology:

- They slow us down to notice the spark “under the skin of our days.”

- They repair the interior where conscience hears “a word not its own.”

- They train fidelity—to people and promises—over performance.

- They lift work from grind to gift.

- They send us upstream toward the Source, against the current of fashion.

Poetry will not pass a law or stop a tank. But it will prepare men and women who can—because it teaches them to see, to remember, and to prefer truth to comfort. That is how a young Pole, formed by loss and labor, learned to resist two totalitarianisms and, later, to speak across borders to an anxious world.

Read him to remember what freedom sounds like when it is spoken softly, steadily - and prevails.

Excerpts cited

- “Song of the Hidden God” (1944)

- “Song of the Brightness of Water” (1950)

- “The Mother” cycle (1950)

- “Thought Is a Strange Space” (1952)

- “The Quarry” (1956)

- “Profiles of the Cyrenean” (1957)

- “The Jeweler’s Shop” (1960)

- “Easter Vigil” (1966)

- “Song of the Earth” (various)

- “Roman Triptych” (2003)

Note: Excerpts reflect widely circulated English renderings of Wojtyła’s poems; translations vary across editions.