The Meaning We Make. Karl Popper and the Rebellion Against Destiny

In closing The Open Society, Popper stripped history of its idols. No destiny guides it, no law redeems it—only the choices of free men and women. He asked us to believe in a harsher hope: that meaning begins where necessity ends.

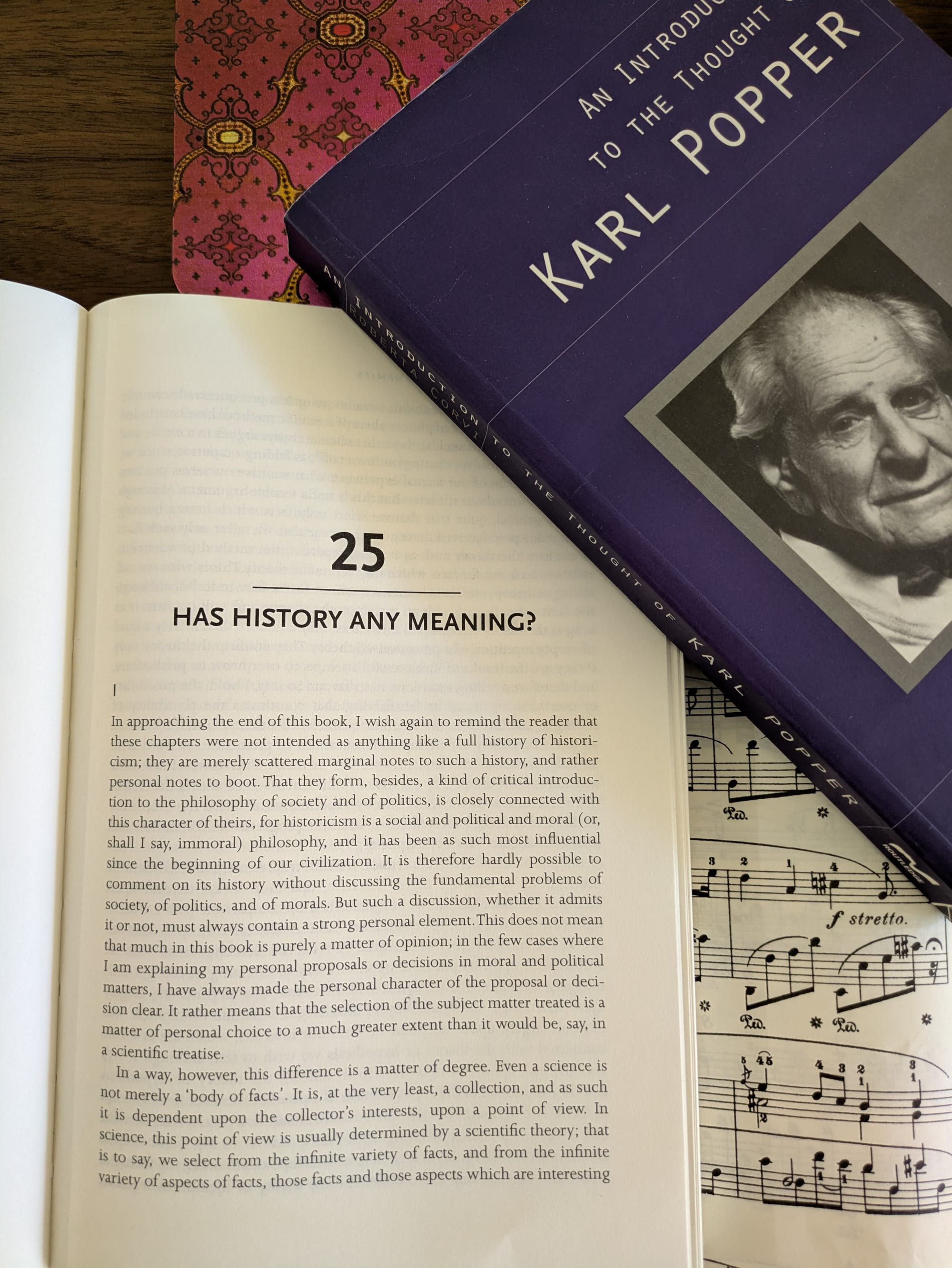

Europe was still breathing smoke in 1945 when Karl Popper closed The Open Society and Its Enemies with an austere provocation: history, he argued, offers no built-in destination. The wars had been waged by men convinced they knew the path of destiny—the dialectic of spirit, the march of class, the revelation of race. Popper’s last chapter, “Has History Any Meaning?”, arrives as a moral antidote to prophecy. He rejects lawlike teleology not to drain life of meaning but to restore meaning to those who must choose it. The book ends, paradoxically, by beginning again—with responsibility.

Popper’s great adversary is “historicism,” the belief that society unfolds according to discoverable laws whose mastery would permit prediction. He traces its prestige from Plato’s nostalgia for a fixed order through Hegel’s romance of necessity to Marx’s scientific eschatology. The error is not noticing pattern but converting pattern into fate, tendency into commandment. Once a “law” is declared, freedom becomes an error and opposition a sin. That is how philosophies become police.

Popper’s great adversary is “historicism,” the belief that society unfolds according to discoverable laws whose mastery would permit prediction.

The Bolsheviks turned Marx’s dialectic of class struggle into a justification for purges—history demanding its next stage. The Jacobins read Rousseau’s “general will” as license to decapitate dissent. In the twentieth century, “racial science” claimed to discern the evolutionary logic of nations, and millions died in obedience to its supposed necessity. Even technocratic modernity, armed with algorithms instead of dogma, flirts with the same conceit: that history’s direction can be calculated, dissent dismissed as statistical noise. Each is a variation on the same error—mistaking patterns for commandments.

Polarization, too, feeds on the moral glamour of inevitability. Each camp imagines itself swept forward by history’s momentum—progressives by the march of justice, reactionaries by the wheel of decay. The rhetoric changes, but the logic endures: opposition is obstruction of the inevitable. The political opponent becomes an obstacle to destiny rather than a fellow citizen within it. Popper saw in this moral absolutism the last mutation of historicism: the substitution of conscience with necessity. In our time, ideology speaks less in prophecy than in metrics, yet the posture is the same—certainty that history has already chosen sides. And once history is imagined as judge, politics becomes prosecution.

The rhetoric changes, but the logic endures: opposition is obstruction of the inevitable. The political opponent becomes an obstacle to destiny rather than a fellow citizen within it.

Against this determinism, Popper wields a simple axiom from his philosophy of science: the future course of human history depends, in part, on future knowledge—discoveries, inventions, ideas—which by definition cannot be predicted by any rational method. “We cannot predict, by rational or scientific methods, the future growth of our scientific knowledge,” he wrote in The Poverty of Historicism (1957). If tomorrow’s knowledge is unpredictable today, then no one can reliably prophesy tomorrow’s history.

From this logical wedge Popper opens a political space. If no law commands history, then citizens can. Not omnipotently, never safely, but sufficiently to matter. He is not naïve—institutions fail, passions riot, reforms miscarry—but the absence of cosmic marching orders is not nihilism; it is the ground of moral agency. In a sentence that deserves to be engraved over parliaments and classrooms alike, he insists: “The future depends on ourselves, and we do not depend on any historical necessity.” (The Open Society, ch. 25.) Destiny abdicates; duty remains.

He is not naïve—institutions fail, passions riot, reforms miscarry—but the absence of cosmic marching orders is not nihilism; it is the ground of moral agency.

Duty, for Popper, assumes the form of piecemeal social engineering: deliberate, limited reforms guided by public criticism and open to reversal. The open society is less a finish line than a method—change by conjecture and refutation, learning by institutional trial. Progress, in this light, is citizenship practicing self-correction. Laws are improved when citizens can contest them; policies are corrected when data can embarrass them; leaders are replaced when votes can humble them. The virtue is not certainty but corrigibility.

Progress, in this light, is citizenship practicing self-correction.

What, then, of meaning? Popper’s refusal of historical telos has often been read as a counsel of despair. It is the opposite. Meaning, he argues, is something we give by choosing and pursuing ends that can be justified to others under conditions of freedom. The craving for a ready-made narrative—the comfort of inevitability—produced in the twentieth century only catastrophe. A society that waits for prophecy to vindicate its hopes will wait until a prophet turns judge.

Popper’s pluralism follows immediately. If meaning is not decreed by history, then no single narrative can monopolize human purpose. This is not relativism but humility structured into politics. Isaiah Berlin would soon describe a world of “many ends which men may seek and still be fully rational” (“Two Concepts of Liberty,” 1958), and Popper’s institutional imagination fits that anthropology: independent courts to check the intoxications of power; a free press to supply the oxygen of criticism; competitive parties to prevent sovereignty from clotting; universities and schools to train citizens in evidence, dissent, and self-correction. The open society lives by habits before it survives by laws.

A citizen who sees opponents as corrigible partners can bear losses without dreaming of enemies. A state that treats criticism as oxygen will keep breathing even when it stumbles.

A citizen who sees opponents as corrigible partners can bear losses without dreaming of enemies.

Popper’s rejection of historical destiny need not scandalize the religious mind. Properly understood, it recovers a truth long embedded in Christian thought: that Providence does not coerce freedom but calls it forth. Jacques Maritain, in Man and the State (1951), wrote that “history is made by men under God, not by God without men.” Providence, in this sense, summons a horizon within which human choice retains its dignity. The Catholic personalists of Popper’s generation, from Emmanuel Mounier to Karol Wojtyła, shared the same intuition: the person is never an instrument of history but a co-author in creation. “Man fulfills himself by acting,” Wojtyła wrote in The Acting Person (1969), and that action, when directed toward the good, participates in God’s own creative freedom. Popper’s open society thus converges, perhaps incidentally, with the Christian anthropology of freedom. Both reject determinism; both entrust meaning to moral agency; both see history not as a cage of necessity but as a field of vocation.

Popper’s open society thus converges, perhaps incidentally, with the Christian anthropology of freedom. Both reject determinism; both entrust meaning to moral agency; both see history not as a cage of necessity but as a field of vocation.

There remains the unignorable ache that Hannah Arendt diagnosed after the same war: peoples exhausted by uncertainty may prefer the false warmth of dogma to the chill of freedom. Popper’s answer is not to invent a softer myth but to ask for harder virtues—intellectual humility, civic courage, constancy in the face of reversals. A society of criticism requires character: the willingness to hold convictions without making them altars, to change course without calling it betrayal, to accept losses without dreaming of purges. The citizen’s discipline is to replace the intoxication of destiny with the steadier work of decision.

A society of criticism requires character: the willingness to hold convictions without making them altars, to change course without calling it betrayal, to accept losses without dreaming of purges.

The chapter’s restraint explains its timing. Written at the close of The Open Society, it refuses the metaphysics that had licensed political nightmares. The nineteenth century’s rival teleologies—idealism and materialism—met in the twentieth as world-system and exterminationist fantasy. Popper’s last word is prophylactic. By denying the mandatory meaning of history, he disarms those who would sacrifice living men to an imagined end-state. “No program of salvation by history,” his pages suggest, “is worth a single freedom lost to ensure it.”

“No program of salvation by history,” his pages suggest, “is worth a single freedom lost to ensure it.”

Popper’s “superstition of destiny” has traded its robes for a dashboard. Where prophets once read stars, analysts read spreadsheets; prediction has become the new providence. We worship the chart’s smooth curve, mistaking trend for truth. Algorithms promise foresight, selling us confidence disguised as care. The faith is modern, the theology ancient: that the future is already written, only waiting to be decoded. Tech utopians speak of “inevitable automation,” as if justice itself were machine-learned. Climate alarm, too, sometimes slips from prophecy to penance; innovation becomes blasphemy against the end-times. Across ideologies, the hymn repeats—progress that cannot reverse, decline that cannot be halted. Historicism survives not in scripture but in code.

Popper’s principle still cuts through the glamour: what tomorrow knows, today cannot prophesy

Popper’s principle still cuts through the glamour: what tomorrow knows, today cannot prophesy. No model can foresee the invention—or the act of conscience—that will expose its limits (The Poverty of Historicism, 1957). Knowledge, he argued, grows not by confirming what we believe but by correcting it.

Every advance is an admission of fallibility. Later thinkers traced the same pattern across the frontiers of science. Thomas Kuhn showed how inquiry itself moves through moments of rupture, when familiar problems dissolve and a new paradigm makes the world intelligible again—a drama of falsification on the scale of civilizations (The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 1962). Even Ilya Prigogine, watching nature rather than theory, discerned the same grammar in matter itself: open systems that evolve through instability, order born from disequilibrium, against determinism and static predictability (Order Out of Chaos, 1984). And beneath them all runs the insight Donald T. Campbell called evolutionary epistemology: knowledge grows as life does—through “blind variation and selective retention” (1960). We advance by trying and erring, by letting ideas struggle for survival until only the tested remain. In that sense, discovery is the moral twin of adaptation: both reward openness, humility, and the willingness to learn from failure.

Taken together, these thinkers form a temperament: reality as experiment, truth as corrigible, progress as the capacity to recover. When applied to politics, the moral becomes plain. A society that mistakes probability for destiny will soon mistake people for variables.

Taken together, these thinkers form a temperament: reality as experiment, truth as corrigible, progress as the capacity to recover. When applied to politics, the moral becomes plain. A society that mistakes probability for destiny will soon mistake people for variables.

The confidence worth keeping is not that we are right, but that we can repair. The finest regimes are those easiest to correct. Popper’s open society channels this scientific ethic into civic form: make errors cheap and reversals possible; prefer local trials to central plans, sunsets to permanence, dissent to unanimity. The most humane societies have learned to prefer dull repair to tragic rescue. This is why the open society must defend the freedom to publish, to teach, to assemble, and to worship—not as decorative rights but as engines of learning.

The most humane societies have learned to prefer dull repair to tragic rescue. This is why the open society must defend the freedom to publish, to teach, to assemble, and to worship—not as decorative rights but as engines of learning.

So, if meaning is ours to shape, what ends should a free people pursue? Popper gives no catechism, and rightly so. He offers instead a discipline: choose ends that do not require silencing rivals; choose reforms that admit reversal; choose means that respect the person. The worst historicisms were not errors of prediction but crimes of contempt. There remains the temptation to shrink meaning to private comfort. Popper does not argue for smallness; he argues against sanctimony. The decisive human tasks—curing disease, extending opportunity, restraining war—are not modest. They are simply not guaranteed. They proceed by trial, not revelation; by institutions, not crusades. And they require citizens who would rather improve the world than perfect it.

So the XXV chapter of Popper's Open Society concludes where the century failed. It denies the fable of inevitability and hands us back a future we cannot outsource. Popper’s sentence remains the most adult one in political thought: “The future depends on ourselves, and we do not depend on any historical necessity.”

Everything ennobling in public life follows from it: accountability, because there is no fate to blame; pluralism, because there is no oracle to obey; hope, because history is not yet written.

Everything ennobling in public life follows from it: accountability, because there is no fate to blame; pluralism, because there is no oracle to obey; hope, because history is not yet written.

Concordia discors—harmony through disagreement—is what this ethic looks like when a culture practices it. No common life without contest; no progress without opponents; no truth without the right to err. The open society is the republic of second drafts. It asks not adoration but effort: to test, to argue, to revise, to try again. The wars were fought by men who worshipped a future they pretended to know. The peace will be kept by those who, rejecting that pretense, do the slow work of choosing—together—the ends by which their children will judge them.

That is the meaning of Popper’s ending: not that history is empty, but that it is open—open enough to be worthy of conscience. ◳

The open society is the republic of second drafts. It asks not adoration but effort: to test, to argue, to revise, to try again. The wars were fought by men who worshipped a future they pretended to know. The peace will be kept by those who, rejecting that pretense, do the slow work of choosing—together—the ends by which their children will judge them.