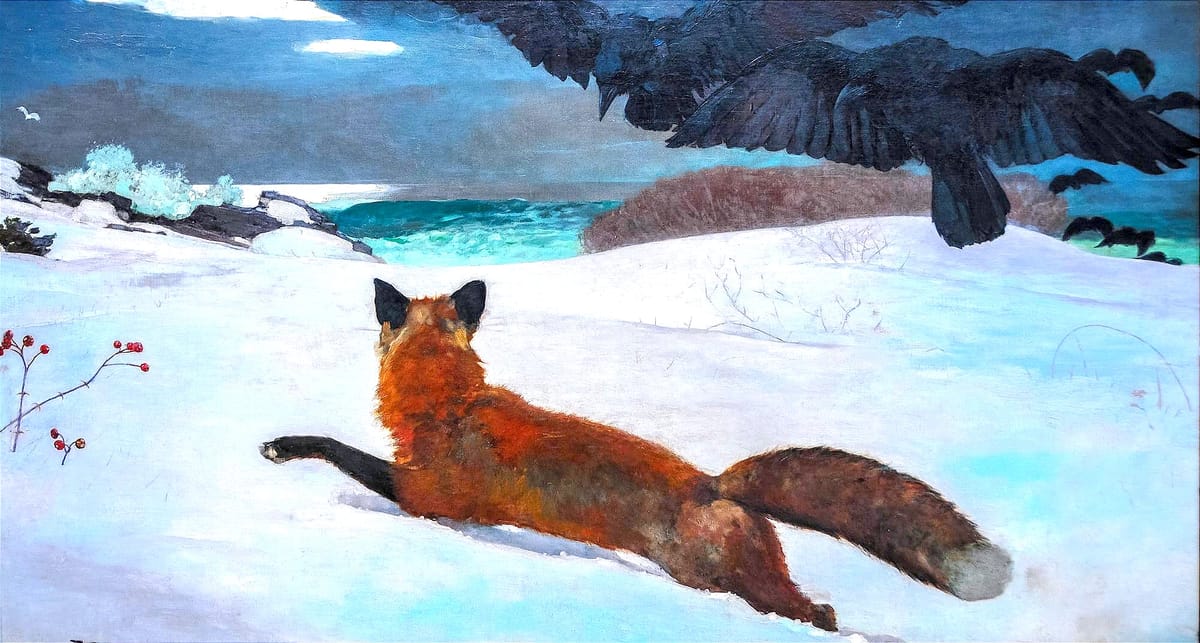

The Agony of the Fox. On Isaiah Berlin's Tragic Wisdom.

In a world that worships the Hedgehog’s certainty, Berlin’s Fox endures—wary, wounded, and free. His agony is the price of plurality: to see the many truths the Hedgehog denies, and to live among them without surrendering to one.

It is a lasting irony of modern thought that a metaphor conceived as a passing amusement has become both Isaiah Berlin’s signature and a lens through which to read the moral anxieties of our time. When Berlin first published The Hedgehog and the Fox in 1953—adapted from his 1951 essay Lev Tolstoy’s Historical Scepticism—he introduced it with wry modesty. His purpose, he said, was to illuminate Tolstoy’s peculiar struggle with history, not to launch a new philosophy. The distinction, Berlin admitted, was superficial and slightly absurd, a parlor game of intellectual temperaments. Yet the metaphor escaped its occasion. In the decades since, it has become a psychological map of modernity itself.

Berlin drew his epigraph from the poet Archilochus:

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

From this gnomic line he built his parable of the mind. Hedgehogs are the monists, the builders of systems. They seek a single unifying vision through which all experience must pass. Plato and Hegel, Dante and Dostoevsky—each is governed by one central idea to which the rest of reality must conform.

Foxes, by contrast, know many things. They live amid particulars, improvising in contradiction, refusing to force coherence upon the flux. Their truths are plural, contingent, incomplete.

Foxes, by contrast, know many things. They live amid particulars, improvising in contradiction, refusing to force coherence upon the flux. Their truths are plural, contingent, incomplete. Shakespeare, Montaigne, and Aristotle belong to this restless species.

Berlin knew the distinction was crude, but its force lay in what it revealed when pressed to its limit. It was not merely a taxonomy of writers—it was a drama within the act of thinking itself. For what happens when the hunger for unity meets the reality of multiplicity? The answer, Berlin argued, is tragedy.

No figure embodied that tragedy more completely than Leo Tolstoy. Berlin saw in him a divided genius: “a fox by nature, but one who believed in being a hedgehog.” Tolstoy’s gift was his inexhaustible sensitivity to the “infinitesimals” of life—the countless motives, hesitations, and accidents that compose history. War and Peace is the supreme literary expression of that vision.

Yet Tolstoy’s mind, Berlin observed, was tormented by its own clarity. He saw the world too well to believe in its order. Every scene he wrote exposed the flux of motives and the futility of tidy explanations. Yet he could not bear that flux. He longed for a single moral or metaphysical law that would reconcile the chaos he so vividly described. His faith demanded unity, but his intellect dismantled it at every turn. Berlin captured this inner war in one of his most haunting images: Tolstoy as a fox who longed to be a hedgehog, “who terribly believed in hedgehogs and wished to vivisect himself into one.” It is the image of a man divided by the very power of his perception—condemned to see plurality clearly, yet unable to rest until it becomes one.

We perceive the world in fragments yet crave its coherence. We are foxes by experience, hedgehogs by conviction.

That self-vivisection, for Berlin, was more than Tolstoy’s personal torment—it was an emblem of modern consciousness itself. We live, as Tolstoy did, between perception and desire: we see the world in fragments yet ache for coherence. We are foxes by experience, hedgehogs by conviction. The more intricate reality becomes, the more desperately we seek a single thread to bind it.

Tolstoy’s assault on “scientific history” was born of this same tension. He rejected the conceit that history could be explained by the will of “Great Men” or by the mechanical laws of progress. Such theories, he argued, confuse the map for the terrain. History, in his view, is a living calculus of innumerable causes—too fine, too interwoven for human reason to compute. To claim mastery of that chaos is not understanding but evasion: a preference for abstraction over life.

Nowhere does Tolstoy expose that illusion more clearly than in his parable of the ram and the shepherd. The ram, indulged and self-assured, imagines he leads the flock; in truth, he is being led to slaughter. His very confidence blinds him to the purpose that governs him. The shepherd’s will is unseen, but absolute. In that image, Tolstoy distilled both the tragedy of the individual and the temptation of intellect—to mistake movement for freedom, and order for understanding.

We, too, inhabit Tolstoy’s parable. We move through digital architectures that promise autonomy yet operate by prediction. The algorithm—our unseen shepherd—does not coerce; it anticipates. It studies our habits, fears, and longings, until choice itself becomes a mirror reflecting our own pattern back to us. What feels like self-expression is often a feedback loop, an echo of desires already mapped and priced. The system guides not by command but by convenience, shaping behavior through frictionless reward. We call this personalization, but it is closer to domestication: a subtle narrowing of the possible beneath the language of freedom.

In Berlin’s terms, it is the triumph of formal liberty over real autonomy. We are permitted to move where we like, so long as our paths remain legible. Like Tolstoy’s ram, we mistake the shepherd’s attentions for evidence of our importance. We graze in statistical pastures, serenely confident of our individuality, while our freedom contracts to the borders of what can be predicted.

Berlin found, in the counterrevolutionary philosopher Joseph de Maistre, a darker answer to the same longing for order that tormented Tolstoy. The two could not have been more different—Tolstoy, the moralist without doctrine; Maistre, the defender of throne and scaffold (an allegory of the death sentence)—yet Berlin saw in both a shared metaphysical dread: a horror of the world’s unpredictability. Each recoiled from the Enlightenment’s faith in reason and progress, from the liberal conviction that life’s disorder could be tamed by reform. Tolstoy sought refuge in moral simplicity, Maistre in sacred violence. “All greatness, all power, all social order depend on the executioner,” Maistre wrote in his St. Petersburg Dialogues (1821). Remove him, and “order gives way to chaos, thrones topple, and society disappears.” For Maistre, sovereignty was not justified by reason but by blood; authority was holy precisely because it was irrational. Where Tolstoy’s despair led to withdrawal, Maistre’s led to worship.

"Berlin called him the “dark hedgehog”: a mind so terrified of disorder that it sanctified violence as the price of meaning. The lineage runs forward through the century—from divine right to ideological terror. The totalitarian mind, Berlin warned, is driven by the belief that human lives can be “slaughtered on the altars of the great historical ideals.” It is the consummate hedgehog, unable to imagine freedom without control.

Our own age, though draped in data and the language of progress, breeds the same creature in subtler form. The positivists of the nineteenth century believed that history obeyed laws; the technocrats of the twenty-first believe that humanity itself can be made to do so. Beneath the rhetoric of innovation lies the same old hunger for the seamless whole—for a world without friction, a society engineered into harmony. Complexity is treated not as the texture of freedom but as a design flaw to be corrected.

Berlin’s warning, drawn from Kant’s line that “out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made,” remains prophetic.

Berlin’s warning, drawn from Kant’s line that “out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made,” remains prophetic. To believe otherwise is arrogance. The conviction that all genuine values are compatible—that liberty can coexist perfectly with equality, or justice with mercy—is the hedgehog’s illusion. Its political form is utopia; its moral form, tyranny.

Against that dream of harmony, Berlin proposed not optimism but restraint—a recognition that freedom resides in imperfection. His philosophy of value pluralism rests on the claim that the moral world is composed of ends “equally ultimate, and claims equally absolute.”

Against that dream of harmony, Berlin proposed a recognition that freedom resides in imperfection - the Kantian crooked timber. His philosophy of value pluralism rests on the claim that the moral world is composed of ends “equally ultimate, and claims equally absolute.” Liberty and equality, loyalty and truth, compassion and justice—each real, each desirable, yet often irreconcilable. To govern, to choose, is to sacrifice one good for another. The task of civilization is not to eliminate such conflicts, but to make them bearable.

Berlin called this the dignity of tragedy. It is the wisdom of limits—the knowledge that the very friction of values is what gives moral life its depth. A society that refuses this tension in favor of a single, total principle invites disaster. The fox, in all his agony, is freer than the hedgehog in his peace.

The fox, in all his agony, is freer than the hedgehog in his peace.

In that sense, Berlin’s pluralism is not a theory of compromise but of courage: the courage to dwell among competing truths without demanding their reconciliation. It refuses the serenity of the absolute for the harder grace of coexistence. The price is unease; the reward, humanity. We inhabit an age that fears uncertainty more than it fears control. To read Berlin today is to remember that freedom is not the absence of friction but the endurance of it—the art of living among imperfect goods.

The fox suffers, but he is alive. The hedgehog rests, but only in his cage. The question, still unresolved, is which peace we are prepared to choose.

And perhaps that, finally, is the test Berlin leaves us: whether we can bear to live without the comfort of the One Big Thing. For to do so—to remain plural, self-questioning, and incomplete—is not simply to think freely. It is to stay human. ◳