Poetry | Papusza: The Forest’s Witness

A Romani poet’s fragile liberty, carried into Polish letters—and into our present arguments about memory, dignity, and belonging

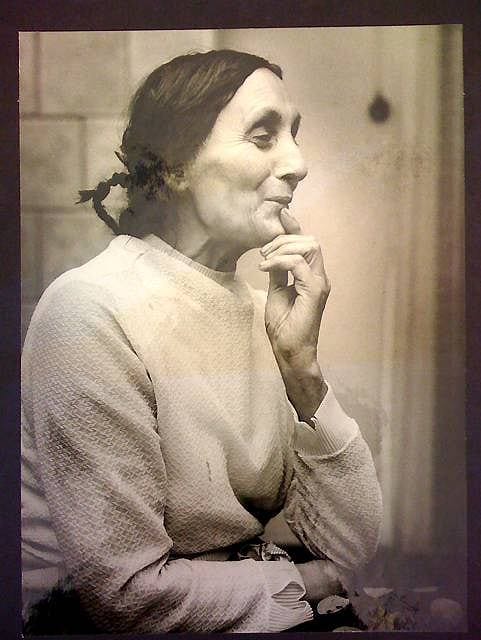

Bronisława Wajs—known as Papusza (“Doll”)—entered Polish literature from the forest edge. A self-taught singer from a traveling kumpania of the Polska Roma, she would become the first widely published Romani woman poet in Poland. Her lyric voice, at once tender and adamant, grafted an oral tradition to the written page. In doing so, she preserved a people’s memory under pressure—from the Nazi genocide, from communist assimilation, and from patriarchal strictures inside her own world. What remains is a poetry of liberty and loss: songs that refuse erasure.

This profile traces Papusza’s path from caravan to canon, and reads several short passages—offered in English renderings—to show how her poems hold together a moral vision: freedom as wandering, nature as sanctuary, memory as resistance.

A short life on the long road

Born around 1908 in Lublin into a family of musicians and harpists, Papusza learned to read in secret, trading chickens for lessons and suffering beatings when discovered. Married at fifteen to an older harpist, she found her voice in sung ballads that drew on Romani storytelling.

War scattered her world. Hiding in the forests of Volhynia during the Nazi occupation, she witnessed the Porajmos—the “Devouring”—the murder of Roma across occupied Europe. After 1945, communist Poland pushed to end nomadism; by the early 1960s wandering would be effectively banned. In 1949 the poet Jerzy Ficowski, living with her kumpania, heard Papusza sing, transcribed her verses, and translated them into Polish. Poems appeared in 1951; Pieśni Papuszy (Papusza’s Songs) followed in 1956.

Fame cost her belonging. Romani elders judged that Ficowski’s ethnographic work had revealed cultural secrets to outsiders. In the early 1950s Papusza was declared mahrimé (ritually unclean) and shunned. She lived largely in isolation until her death in 1987. Posthumously, translations, anthologies, and a 2013 biopic restored her public standing. But the poetry already contained its own vindication.

Reading Papusza: four moments, four meanings

Papusza’s poems are short, flowing, and imagistic. They do not announce a program; they evoke a world—rivers, winds, firelight—as a moral language of freedom. The following brief lines (translations vary across editions) illustrate her range.

1) Childhood and the forest

“In the forest I grew like a shrub of gold,

born in a Gypsy tent.”

Two images do most of the work: the forest as cradle and the “shrub of gold” as a small but dignified life. Nature is not décor; it confers status. Against the settled world that calls Roma marginal, Papusza reverses the gaze. The forest is the center, the schooling of freedom.

“Because no one can understand me,

only the forests and streams.”

The tenderness cuts both ways: liberty entails loneliness. The poem registers a universal truth of exile—freedom as self-possession can mean speech without audience. In Polish literary terms, it answers the country’s own tradition of pastoral nostalgia with a minority’s version: not the manor and meadow, but tent and riverbank.

2) Wonder under a fragile sky

“I look here, I look there—

in warm water the Moon bathes.”

A childlike astonishment animates the line. The cosmos comes close—moonlight in a stream—yet the simplicity is not naïveté. In Papusza, wonder is moral discipline: the world is still gift, even after catastrophe. That posture resists the cynicism born of persecution, a refusal to let suffering define the totality of reality. Polish readers used to tragic irony hear in her voice a parallel music—clarity without bitterness.

3) Witness to annihilation

“Blind our enemy, so the child can live.”

A prayer, not a manifesto. In “Tears of Blood,” her poem about Volhynia, the address is to the stars and the dawn—a liturgy improvised in terror. The child stands for the continuance of a people. This is testimony shaped by song: fragmentary, incantatory, yet unmistakably historical. It broadens the memory culture of wartime Poland by insisting that the Roma were not folklore on its margins but victims and witnesses within its core tragedy.

4) Rivers as a politics of freedom

“The water does not look behind;

it runs farther away.”

A metaphor for the open road, and a critique of forced settlement. Under communist “Action C” and later measures, wandering was curtailed, camps registered, livelihoods re-engineered. Papusza’s river replies that human dignity includes movement—not vagrancy as pathology but itinerancy as vocation. The line is political without slogans: it defends liberty by defending a way of life.

Between worlds: Polish letters and Romani guardianship

Papusza’s art stands at a hard crossing. Thanks to Ficowski, she entered the Polish canon—endorsed by figures like Julian Tuwim—while becoming suspect among her own for crossing a boundary of disclosure. The tension matters. It shows the costs of mediation: to translate is to risk betrayal; to remain silent is to accept invisibility.

For Polish literature, her arrival widened the frame. Here was a lyric not born of salons or universities but caravans and campfires, a voice that braided folk imagery with historical witness. She showed a majority culture its blind spots: the “Gypsy” of comic relief or dangerous myth replaced by a mother, a girl, a people under sentence.

For Romani guardianship, the fear was not irrational. Secrecy shields the vulnerable. Yet Papusza’s banishment reveals a tragic bind: the same act—bringing a hidden world into print—can be both a wound to communal privacy and the sole path to cultural survival in a world that archives what it recognizes and forgets what it never hears.

What her poems teach about liberty

Papusza’s work speaks a language that liberal and conservative readers alike can hear. A few lessons stand out:

- Liberty as form of life, not abstraction. The poems do not argue for “freedom of movement” in policy terms; they stage a life in which movement, season, and song are constitutive goods. Political orders that reduce freedom to paperwork miss a deeper anthropology.

- Memory as justice. Her wartime poem turns lyric into testimony. Where archives fail, poetry remembers. This is not sentimentality; it is moral accounting—naming the Roma dead as part of Europe’s ledger.

- Pluralism with limits. Papusza’s ostracism and her resistance to communist assimilation both warn against coercive unities—whether demanded by the state or imposed by communal conformity. True pluralism protects the fragile space where a person can choose to speak—even across taboos—without being erased.

- Nature as moral partner. The forest and river are not escape hatches from politics; they are measures of it. When regimes deny legitimate wandering, they set themselves against the grain of creation—what older Christian democrats called the natural law of human association.

Why she matters now

Across Europe, Roma communities still face harassment, eviction, and caricature. In cultural debates, they are too often discussed rather than heard. Papusza is not a policy blueprint; she is a standard of attention. Her poems force readers to notice what Poland—indeed, what modern Europe—has often relegated to the picturesque: a people insisting on dignity without ceasing to be themselves.

For Polish poetry, she is a canonical outsider: a singer who brought the forest into the city and made it speak. For the rest of us, she is a test we can pass: can we hold together memory and mercy, freedom and responsibility, the claims of community and the rights of conscience? Isaiah Berlin warned that ultimate goods can collide; politics is the art of stewarding those collisions without cruelty. Papusza shows what it looks like when a single conscience, small and steadfast, keeps faith amid the crash.

A final image

Papusza’s lines often return to the hearth:

“Oh, how beautifully by the tent the fire burns.”

The scene is homely and threatened: warmth at the edge of a cold world. The tent could be any minority neighborhood, any migrant shelter, any household where vulnerability and courage live together. The fire is culture. The poem is the hand that keeps it from going out.

Papusza remains the emblematic Romani poet of Poland because she faced the paradoxes of freedom with clarity and grace. In an age quick to mythologize or to forget, her songs do neither. They remember.