Norwid's Humble Freedom

How a forgotten Polish exile became John Paul II’s moral compass—and why his austere vision of liberty matters for democracy today

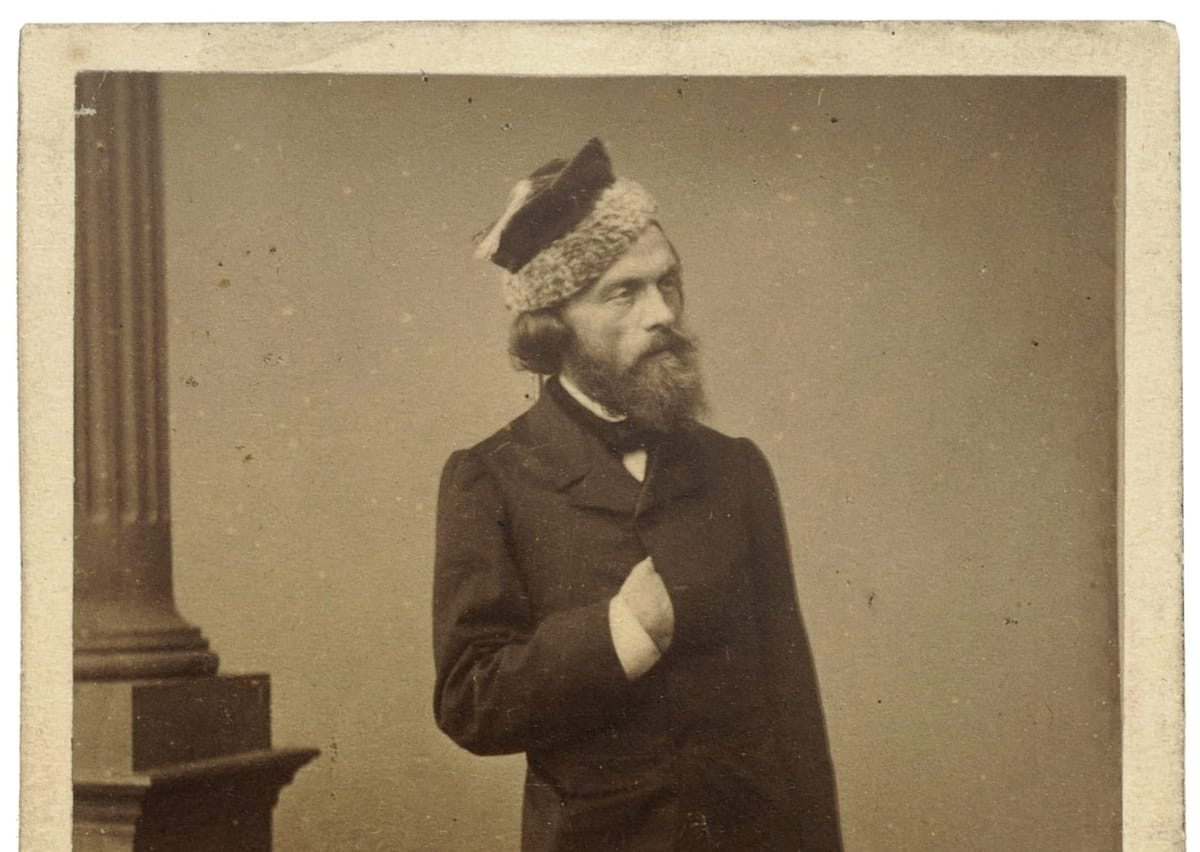

In 1883, Cyprian Kamil Norwid died in obscurity in a Paris almshouse. His poetry was unread, his grave unmarked. Born in 1821 to a Poland erased by imperial partitions, he endured poverty and illness, wandering through Europe and America. His dense, ironic verse, laced with dashes, silences, and paradoxes, puzzled contemporaries who preferred the fiery Romanticism of Adam Mickiewicz. Yet a century later, Karol Wojtyła—Pope John Paul II—hailed him as one of Christian Europe’s greatest poets, drawing on his moral vision to resist Communism.

Today, as democracies strain under polarization, misinformation, and the erosion of community, Norwid’s austere vision of freedom—rooted in conscience, truth, memory, and work—offers a profound guide. A poet ahead of his time, his blend of Polish identity, Christian universalism, and sharp irony challenges us to live freedom as a disciplined act.

Cyprian Kamil Norwid

Norwid's life mirrored Poland's erasure. By 1795, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had been partitioned by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Orphaned early, Norwid left Warsaw at twenty-one, roaming Berlin, Rome, Paris, London, and New York. As an engraver, painter, and sculptor, he scraped by, crafting poetry and dramas that fused classical restraint with Romantic passion.

His "hieroglyphic" style—marked by dashes, italics, and deliberate silences—defied Romantic norms, earning him accusations of being "unintelligible." This obscurity was deliberate, using irony to critique societal flaws and demand active reader engagement. His innovative form, akin to the later experiments of Charles Baudelaire or Gerard Manley Hopkins, anticipated modern poetry's complexity, mixing Polish roots with universality.

Cyprian Norwid’s philosophy of liberty was a radical departure from the revolutionary romanticism of his time. He argued that freedom was not an external condition to be won on the battlefield, but an internal state to be cultivated in the soul. This core belief is powerfully distilled in his short fragment, Wolność? (Freedom?), which defines liberty as a matter of inner conviction:

Freedom? — it is not given from without, but within, And only within is it lost — or known, Like conscience...

This redefinition of freedom as an inner responsibility is the key to his thought. The philosophy is most clearly articulated in his 1869 treatise Rzecz o wolności słowa (On the Freedom of Speech), where he distinguishes wolność mówienia (the mere freedom to say, “la liberté de dire”) from a morally accountable wolność słowa (freedom of the Word), which is rooted in sumienie (conscience). There, he insists that free speech without inner obligation is only noise, whereas genuine freedom requires the “świętość słowa” (sanctity of the word) and citizenly self-restraint.

Akin to that ethic of inner responsibility, Norwid grounds liberty in the dignity of daily life—and above all, in work. In his 1851 dialogue-poem Promethidion, he elevated labor from mere toil to a sacred act of communal and spiritual renewal:

Because the light is not to stand under the bowl, nor the salt of the earth for kitchen spices, Because beauty is to enthuse us for work— and work is to raise us up.

By championing work as the foundation of a free society, Norwid offered a powerful alternative to the widespread myth of Poland as the "Christ of Nations." Popularized by the great Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, this messianic belief framed Poland’s 19th-century suffering under imperial partitions as a holy, Christ-like sacrifice destined to bring future liberty to all of Europe. Norwid found this focus on glorious martyrdom to be a passive and dangerous fantasy. He argued instead that a nation truly rises not through suffering, but through the creative, dignified labor of its people.

Long before the age of social media and viral falsehoods, Cyprian Norwid saw that a society's moral health was built on a foundation of truthful words. For him, conscience wasn't just a private feeling; it demanded a public defense of language itself. In his 1869 treatise Rzecz o wolności słowa (On the Freedom of Speech), he issued a prophetic warning against the empty calories of irresponsible expression. He staged a war between two figures: the "author," who accepts the sacred duty of wrestling with truth, and the "vulgarizer," who peddles cheap outrage and drowns meaning in noise.

Norwid believed even our political structures should be built on this foundation. He brilliantly re-imagined "parliament" not as a place for power plays, but through the lens of "parabolment"—a shared space for telling the parables that forge collective meaning. This vision of language as a sacred trust feels more urgent than ever in our age of fractured discourse. His own poetic style was an act of resistance against lazy thinking. His poems are intellectual obstacle courses, where dashes create chasms of silence and questions demand the reader's active participation. He insisted on clarity in a world of moral fog, as in his poem Królestwo (Kingdom):

— Truth? it is not a mixture of contradictions. An eagle? it is not half-turtle, half-thunder.

This devotion to truth made Norwid a fierce critic of mob sentiment. His tragic irony burns brightest in the 1876 poem Coś ty Atenom zrobił, Sokratesie? (What Did You Do to Athens, Socrates?). In this timeless meditation on the fate of the truth-teller, he shows how societies build pedestals for the visionaries they first execute. Norwid laments that the ultimate crime is not the unjust act itself, but the collective, comfortable refusal to name it as such. In doing so, he reminds us that the first victim in an age of populism is not just the inconvenient genius, but truth itself.

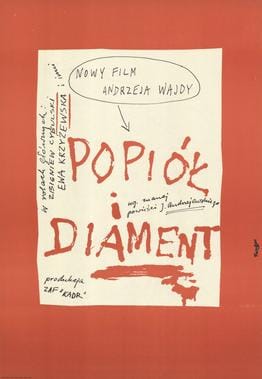

A lesser-known but equally profound poem, In a Notebook (W pamiętniku), provides a visceral illustration of Norwid's philosophy of inner struggle. The poem gained modern fame through its haunting inclusion in Andrzej Wajda’s 1958 film, Ashes and Diamonds, which questioned the purpose of Polish anti-Communist resistance.

In the poem, Norwid describes a journey to a personal Hell, a place not of fire and brimstone, but of "studies of our human hearts," where "there are no feelings, but only structures." It is a hell of dehumanizing routines, where a "useless, pointless machinery" of life beats "like blunt spikes stiffly driven in." This is a profoundly modern vision of alienation, of a life without purpose or genuine emotion.

Norwid then describes the "furious rage" this pointless existence provokes, a feeling that becomes "a trial and a measure" of one's character. He asks if, after being stripped of all inherited identity—tradition, family, style—one is left with anything of value:

Will remain only ashes, storm and chaos, To be swept straight into the abyss, Or will remain there a shining diamond, The light of the dawn of everlasting triumph?

This final, iconic question, read by a young man in the film, became a defining symbol for a generation trying to find meaning in the chaos of war and political subjugation. The "diamond" is not a political victory, but the raw, unadulterated self that emerges after the fire of suffering. The poem’s ending, with the narrator preferring to "take off on double-ended roads" with a silent companion, suggests that the true journey is not a social or political one, but a solitary quest for authenticity beyond the mundane chatter of history.

Norwid’s work affirmed that freedom is not an isolated condition but a universal responsibility tied to both history and global community. In his poem Chopin’s Piano (Fortepian Szopena, 1863), he transformed a Russian act of destruction—soldiers smashing the composer's piano—into a symbol of endurance.

They cast it from the window! — down it flew, to smash upon the cobbles with a cry… And though its strings were broken, its echo remained, a memory no tyrant could silence.

The poem’s dashes mimic the crash and its lingering echo. Norwid saw culture as a form of resistance, preserving identity against oppression. His poem The Past (Przeszłość) reinforces this, portraying history not as a shadow but as a root. In our digital age, where memory fades into fleeting feeds, Norwid’s call to preserve culture as a moral force is urgent.

This sense of shared humanity extended across borders. In his 1859 poem To Citizen John Brown, he mourned the American abolitionist, linking Poland’s oppression to the fight against slavery. Liberty, he implied, is indivisible: denying it anywhere harms it everywhere. This cosmopolitan stance, rooted in Christian universalism, offers a model for today’s global crises.

Karol Wojtyła’s relationship with Norwid began not in the Vatican but in the shadows of Nazi-occupied Kraków. As a young man, Wojtyła was a key member of the underground Rhapsodic Theatre, an clandestine group that used the power of the poetic word as an act of cultural and spiritual resistance. Performing Norwid’s dense, morally serious dramas and poems was a way to keep the soul of Poland alive when its body was imprisoned. This early, formative experience taught Wojtyła that culture was the very bedrock of a nation's identity and survival—a core Norwidian belief.

The kinship between the 19th-century poet and the 20th-century pope was built on several shared pillars, which Wojtyła would later develop into formal Catholic teaching.

Christian Humanism: At the heart of both men’s thought is an unwavering focus on the dignity of the human person. For Norwid, this dignity was expressed through conscience, creative work, and the search for truth. For John Paul II, this became the central theme of his first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis (The Redeemer of Man), which argues that the human person is the primary route for the Church. He saw in Norwid a powerful ally against ideologies (like Communism) that reduce human beings to mere cogs in a political or economic machine.

The Gospel of Work: Norwid’s greatest philosophical gift to Wojtyła was his theology of work. In Promethidion, Norwid presented labor not as a curse or mere drudgery, but as the primary way humanity co-creates with God, finds dignity, and builds community. This poetic vision became theological doctrine in John Paul II’s 1981 encyclical Laborem Exercens (On Human Work). The document, written in the midst of the Solidarity movement in Poland, is pure Norwid in its insistence that the human being is the true subject of work, and that labor must serve the person, not the other way around.

Culture as the Arena of Freedom: Both Norwid and Wojtyła understood that political and military oppression could conquer a nation's territory but not its soul. In his historic 1980 address to UNESCO, John Paul II articulated a quintessentially Norwidian idea: that Poland, despite being erased from the map for over a century, survived entirely through its culture. Culture—its language, faith, and art—was the sacred space where the nation's identity was preserved.

"I am the son of a nation which has lived the greatest experiences of history, which its neighbors have condemned to death several times, but which has survived and remained itself. It has kept its identity, and it has kept, in spite of partitions and foreign occupations, its national sovereignty, not by relying on the resources of physical power, but solely by relying on its culture. This culture turned out in the circumstances to be more powerful than all other forces."

Pope John Paul II, Address to UNESCO, June 2, 1980.

Ultimately, John Paul II turned to Norwid because Norwid was a poet for difficult times. He offered no easy patriotism or simple piety. Instead, he demanded a "difficult freedom" rooted in conscience, truth, and the hard labor of building a just society. For a pope confronting the moral complexities of the Cold War, Norwid provided a spiritual blueprint that was neither capitalist nor communist, but profoundly Christian and human. He was, for Karol Wojtyła, the poet of a freedom that had to be earned daily, both in the soul and in the world.

Norwid’s legacy is a challenge: freedom is a habit, sustained by conscience, truth, memory, work, and dialogue. His epigram still bites: “It is not difficult to die for freedom—it is far more difficult to live for her.”

In a world where freedom is mistaken for consumption, memory fades into digital noise, and division drowns out dialogue, Norwid’s call to live freedom as daily bread—not a fleeting feast—urges us to rebuild civic life. His timeless vision, both deeply Polish and universally human, challenges us to preserve truth, beauty, and work as acts of resistance. ◳

Think Beyond Tribes | Liberty • Conscience • Pluralism | Concordia Discors Magazine | 𝕏