Syria’s Future Depends on Pluralism

Isaiah Berlin and Leszek Kołakowski offer a blueprint: Only inclusive, pluralist statecraft—not imposed power—can bring Syria back from the brink. The international community must insist on it.

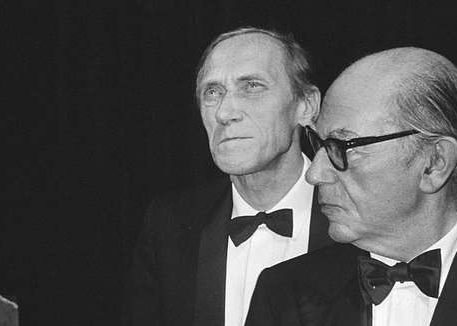

Two Thinkers for a Broken Land

Syria’s war has now spanned nearly a decade and a half, leaving more than half a million dead, millions displaced, and a social fabric frayed almost beyond repair. Every international formula tried so far—top-down settlements, military truces, power-sharing gestures—has faltered. The fall of Bashar al-Assad in December 2024 raised hopes for renewal, but the provisional constitution unveiled by his successor, Ahmed al-Sharaa, already shows the familiar signs of authoritarian centralization. Elections scheduled for September 2025 exclude large swathes of the population; minorities remain vulnerable; massacres and sieges continue. Diplomats speak of “stability,” but Syrians know how fragile that word has become.

What, then, could two philosophers—one a Latvian-born British liberal theorist, the other a Polish dissident who broke with Marxism—offer to policymakers navigating this tragedy? Isaiah Berlin and Leszek Kołakowski lived through the wreckage of twentieth-century utopias. Each warned against the temptation to force harmony upon diverse societies. Each argued, in his own register, that genuine politics means accepting conflict, contradiction, and permanent tension. Their ideas are not academic luxuries; they are survival tools for fractured states. For diplomats and mediators struggling to shape Syria’s future, Berlin and Kołakowski provide not solutions but orientation—a grammar of statecraft that insists on pluralism as the only path out of ruin.

Each warned against the temptation to force harmony upon diverse societies. Each argued, in his own register, that genuine politics means accepting conflict, contradiction, and permanent tension.

Berlin’s central claim was stark: politics is not the art of dissolving conflict but of managing it. “The world that we encounter in ordinary experience,” he wrote, “is one in which we are faced with choices between ends equally ultimate, and claims equally absolute” (Two Concepts of Liberty, 1958). Liberty, equality, faith, belonging—none can be absorbed into the others. Attempts to impose a “final harmony,” Berlin argued in The Pursuit of the Ideal, are “not merely unattainable… but conceptually incoherent.” When translated into programs of power, they produce tyranny.

Kołakowski, having witnessed the betrayals of communism in Poland, offered a complementary realism. In is essays he insisted: “There never have been and never will be improvements that are not paid for with deteriorations and evils.” Politics is tragic; every reform extracts a price, warning that the quest for total consistency was a recipe for oppression. True wisdom tolerates contradiction and makes space for it in institutions. “The price of our freedom,” he later observed, “is permanent tension.”

Together, these two thinkers map three imperatives for diplomacy:

- Accept trade-offs—abandon the fiction of perfect solutions.

- Design for diversity—institutionalize coexistence rather than uniformity.

- Distrust anyone promising unity without remainder—they are selling coercion.

Syria exemplifies both the necessity and fragility of pluralism. Its cultural mosaic—Christians, Druze, Alawites, Ismailis, Kurds, Turkmen, Armenians, Sunnis, Shi‘a—was not an anomaly but the essence of the country. Yet the modern state never built institutions capable of sustaining this diversity. Under Hafez and Bashar al-Assad, minorities were tolerated symbolically but denied real autonomy; Kurds were long stripped of citizenship; Turkmen were politically invisible. Authoritarian patronage stood in for genuine pluralism. The 2011 uprising exposed the brittleness of this arrangement. As violence escalated, sectarian fears deepened, and ISIS’s brutality threatened whole communities with extinction. By 2025, Syria’s Christians—once 10 percent of the population—had dwindled to a fraction, some estimating fewer than 300,000 remain.

The post-Assad order risks repeating the pattern. President Sharaa’s interim constitution centralizes power, reserves a third of parliamentary seats for presidential appointees, and excludes Kurdish and Druze areas from elections on “security” grounds. Coastal massacres of Alawites in March 2025 and the siege of Druze in Sweida this summer are grim evidence that centralization without pluralism invites atrocity. Berlin’s warning in The Crooked Timber of Humanity rings with chilling clarity: “The conviction that there is one true solution… is the most dangerous illusion of them all.”

Against this background, the August 2025 Hassakeh conference was a remarkable counterpoint. More than 400 representatives—Druze, Alawites, Christians, Kurds, Ismailis, Turkmen, and Sunnis—declared their commitment to decentralization and constitutional guarantees. “Syrian identity includes all Syrians,” their statement affirmed. For them, pluralism is not imported rhetoric but survival. As one analyst noted, “Only time, major engagement and effort build trust and understanding.” Hassakeh was a modest step, but it gave institutional form to Berlin’s and Kołakowski’s intuitions: no grand harmonies, only bargaining, restraint, and co-existence.

What does it mean to translate these insights into Syrian statecraft? Four institutional commitments stand out:

- Rights before rulers: A Bill of Rights guaranteeing religious freedom, equal citizenship, and language protections, enforced by a constitutional court representing all communities.

- Shared executive power: A grand-coalition presidency or rotating vice-presidencies to prevent domination by any single bloc.

- Serious decentralization: Local authority over education, policing, and cultural life, with national transfers—federalism for concord, not partition.

- Targeted minority vetoes: Powers limited to red-line harms—forced displacement, suppression of language or religion—not a license for paralysis.

Comparative cases warn and inspire. Lebanon shows how rigid quotas ossify. Bosnia shows that imperfect power-sharing can still prevent war. Switzerland shows that federalism can anchor prosperity. Syria’s version will be its own, but the design principle must be pluralist: strong enough to protect rights, weak enough to fear abusing them.

For diplomats and donors, the implications are clear:

- Do not confuse control with legitimacy. Recognition and aid must be tied to pluralist milestones, not to electoral theatrics.

- Fund the anchors of inclusion. Support minority councils, interfaith initiatives, and local oversight bodies as the scaffolding of trust.

- Insist on accountability. Massacres in Latakia, Tartus, and Sweida must be investigated impartially; impunity will drive minorities either to arms or to exile.

Pluralism is not merely a moral stance; it is strategic common sense. Plural states are harder to hijack, less likely to incubate extremism, and more likely to attract diaspora capital. Lose minorities, and Syria loses the connective tissue essential for recovery.

Pluralism is not merely a moral stance; it is strategic common sense. Plural states are harder to hijack, less likely to incubate extremism, and more likely to attract diaspora capital. Lose minorities, and Syria loses the connective tissue essential for recovery.

Kołakowski’s realism and Berlin’s pluralism converge on one truth: politics without tension is a lie. Syria’s future will not be utopian, but it can be decent—if difference is given legal shelter rather than crushed under central authority. Every attempt at a “final solution”—Assad’s authoritarian secularism, Islamist monism, Sharaa’s centralization—has ended in ruin. What remains is compromise, tension, and negotiation institutionalized.

Diplomats and policymakers should take note: monism has failed, force has failed, patronage has failed. The only peace with any chance of endurance is pluralism as statecraft.

Diplomats and policymakers should take note: monism has failed, force has failed, patronage has failed. The only peace with any chance of endurance is pluralism as statecraft.