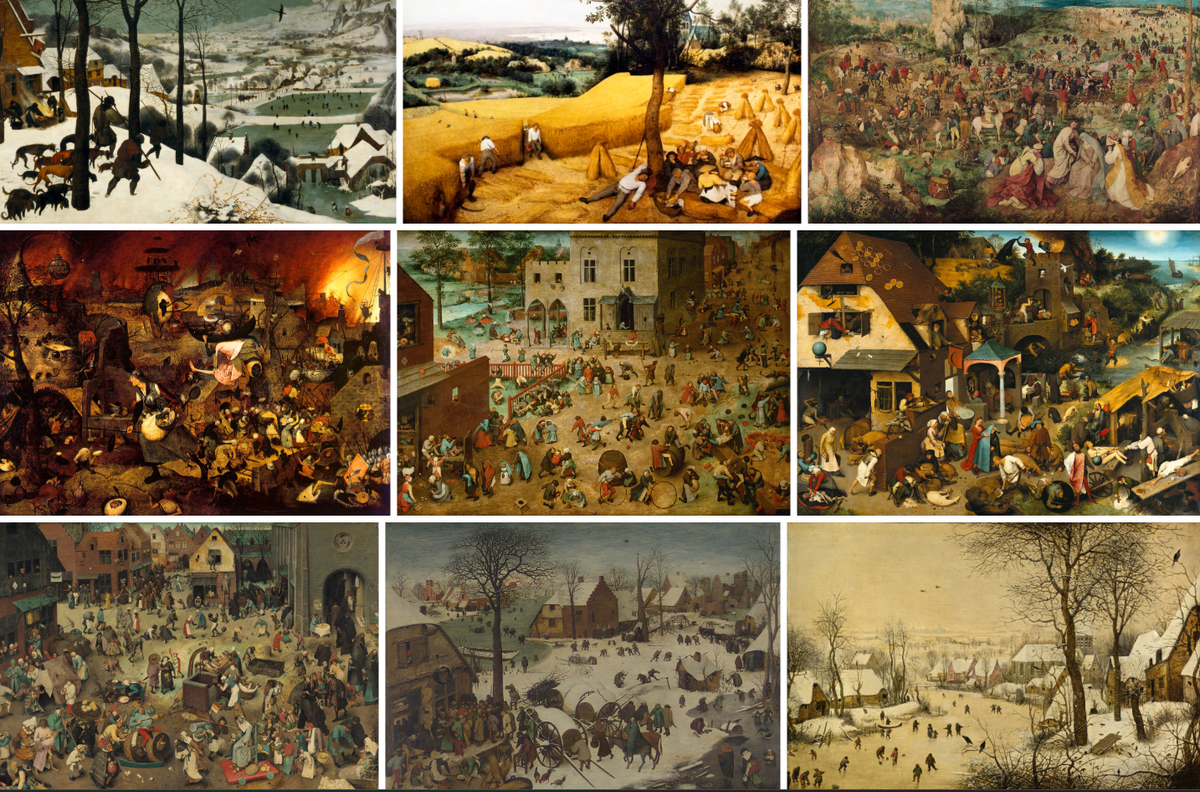

Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Painter of Crowds, Contradictions and Concordia Discors.

Bruegel’s paintings are maps of collective life, crowded, contradictory, and held together by rhythm rather than agreement. Long before modern theory, he showed how societies endure without resolving their differences.

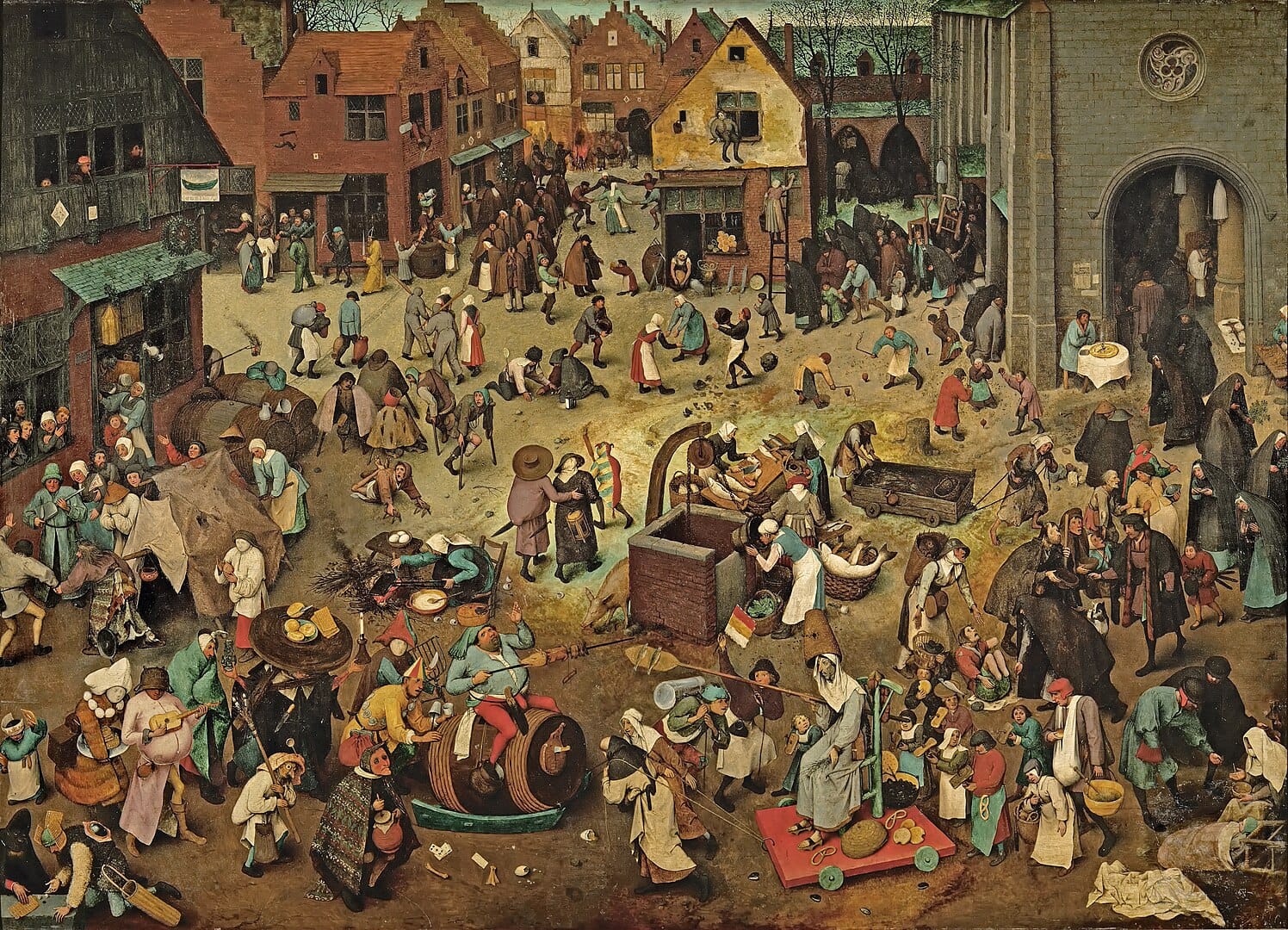

Some paintings reward a single glance; others repay a lifetime of looking. The Fight Between Carnival and Lent belongs to the latter. We return to it because it never stops disclosing itself. Each encounter reveals another gesture, another contradiction. A painting that does not resolve. It behaves, instead, like a society.

The scene is a town square, ordinary, almost obstinately so. A tavern spills noise and grease at one end; a church gathers discipline and silence at the other. Between them, the square holds. Carnival advances on a barrel, swollen with appetite; Lent answers, thin and intent. They do not collide. They pass. Two moral worlds, fully present, fully legitimate, already accustomed to sharing the same ground. The temptation is to read the image as allegory, to ask which impulse prevails. Pieter Bruegel the Elder resists that demand.

His insight is quieter, more durable. Carnival knows Lent is coming; Lent remembers Carnival. Their antagonism is present at every corner. What is powerful, is that conflict is neither denied nor conquered in this painting; it is given a rhythm.

This sense of time, of social life held together by recurrence rather than agreement, runs through all of Bruegel’s work.

It animates his crowded streets where children rehearse the gestures of adulthood long before they understand them; it shapes his villages of proverbs, where incompatible truths circulate side by side without canceling one another; it governs his winter landscapes, where survival depends on adaptation to seasonal conditions no one controls.

Even when Bruegel turns to catastrophe, whether the overreaching ambition of Babel or the relentless procession of death, he does not abandon this logic. Systems fail, bodies perish, but the interest remains the same: how collective life organizes itself under pressure or leisure.

Born around 1525 in the Duchy of Brabant and dead in Brussels by 1569, Bruegel lived at a hinge of European history, when religious unity fractured into rival certainties and images themselves became instruments of persuasion and threat.

Many artists of his time sharpened distinctions. Between orthodoxy and heresy, salvation and error. Bruegel did something stranger. He looked outward, toward the surface of communal life, where people continued to share streets and seasons even as metaphysical agreement slipped away.

Many artists of his time sharpened distinctions. Between orthodoxy and heresy, salvation and error. Bruegel did something stranger. He looked outward, toward the surface of communal life, where people continued to share streets and seasons even as metaphysical agreement slipped away.

Bruegel uniqueness is of course in the sympathy for ordinary people, but it is his refusal to simplify them that makes him shine today. He does not organize the world around heroes or villains. He organizes it around habits. Around meals, games, weather, proverbs, routines of the daily life.

Bruegel uniqueness is of course in the sympathy for ordinary people, but it is his refusal to simplify them that makes him shine today. He does not organize the world around heroes or villains. He organizes it around habits. Around meals, games, weather, proverbs, routines of the daily life.

His paintings are crowded because societies and human existence are crowded. Meaning does not descend; it accumulates.

An early biographer, Karel van Mander, tells us that Bruegel attended village weddings disguised as a peasant, blending in, observing. Whether literal or emblematic, the story captures that Bruegel did not stand above his world. He entered it. He trusted it.

That trust is what gives his work its peculiar authority. He understands that harmony rarely announces itself, and that order often emerges from endurance of daily existence, from people continuing to occupy the same spaces, repeat the same rituals, adjust to the same constraints, even as their beliefs pull them in different directions.

In The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, Bruegel shows us two societies occupying the same square, not reconciled, not resolved, but recognizably bound.

The achievement is continuity. A shared world persists, held together by time, by practice, and by the knowledge that tomorrow will require the same accommodations as today.

Bruegel does not explain civic virtue. He lets it appear. In place of instruction, he offers a discipline of seeing—one that neither flinches from discord nor rushes to abolish it. ◳