Leszek Kołakowski: From Marxist Theorist to Critic of Utopia

From Party prodigy to dissident sage, Kołakowski’s journey shows how the courage to doubt can be freedom’s deepest defense.

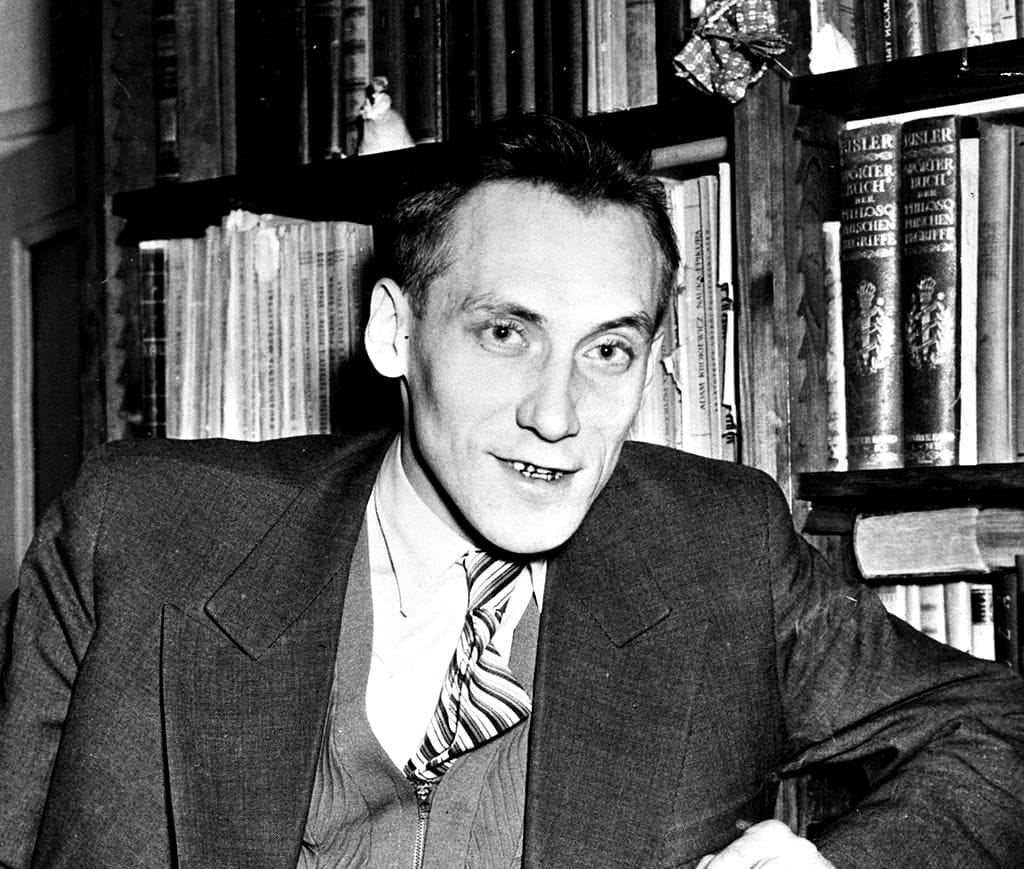

Leszek Kołakowski (1927–2009) lived a life that could be read as the intellectual autobiography of the twentieth century itself: born in the ruins of war, drawn into Marxist faith, scarred by disillusion, and finally a prophet of pluralism and limits. He began as an orthodox Marxist, became Poland’s most notorious heretic, and ended as one of the sharpest critics of ideology in all its guises. His story is not merely the fall of an illusion but the discovery of freedom in doubt.

“In philosophy,” he once wrote, “we look for the truth but never find it. We need the discipline of doubt, for nothing is so fatal to liberty as the belief that liberty is secure.” (Modernity on Endless Trial).

From Orthodoxy to Heresy

Kołakowski joined the Polish United Workers’ Party in 1945, rising quickly as a brilliant young philosopher at Warsaw University. His early work, on Spinoza and Marxist humanism, was deeply orthodox. Yet his Moscow study trip in 1950 revealed the banality of “Soviet paradise,” while the 1956 Polish thaw gave him space to voice discontent.

By 1957 he had published What Is Socialism?, a pamphlet that cut against the official line and was promptly banned. Two years later, in The Priest and the Jester, he sketched two archetypes: the priest, who guards eternal truths, and the jester, who unsettles them. “The jester’s role,” he wrote, “is to remind us no truth is final.” That declaration foreshadowed his break with Marxist dogma and his adoption of the jester’s vocation—irreverent, probing, skeptical, but never nihilist.

By 1966 his criticisms of the Party had earned him expulsion. In 1968, amid the regime’s anti-revisionist purges, he was dismissed from his university chair and forced into exile. Far from silencing him, this amplified his voice. His essays circulated in Poland’s underground “flying universities,” sustaining a dissident intelligentsia. Adam Michnik would later confess: “Each of us is to some extent Kołakowski’s pupil.”

Autopsy of a Doctrine

In exile at Oxford, Kołakowski completed his intellectual break. Main Currents of Marxism (1976–78), his three-volume history, remains the most exhaustive—and devastating—account of Marxism ever written. With cool detachment he traced Marxism’s lineage from Hegel to Stalin, showing how the utopian impulse carried within itself the logic of coercion.

“Marxism was the greatest fantasy of our century,” he concluded, “a dream of perfect unity which in practice bred perfect servitude.” The brilliance of Main Currents is its refusal to reduce Marxism’s crimes to mere accidents. Stalinism was not a distortion of Marx but a fulfillment of its utopian structure. A doctrine that abolishes limits, Kołakowski argued, necessarily abolishes freedom.

For dissidents behind the Iron Curtain, Main Currents was an arsenal. For the West, it remains a classic meditation on how noble ideals collapse into tyranny when they deny pluralism.

Beyond Marxism: Themes in Kołakowski’s Thought

Human dignity and the limits of politics

Kołakowski’s political philosophy always returned to a simple, non-negotiable foundation: human dignity. “It is difficult to define what human dignity is,” he admitted. “It is not an organ to be discovered in our body… but without it we would be unable to answer the simple question: what is wrong with slavery?” (Is God Happy?). For him, politics without dignity was merely technique, prone to the “rational” justifications of cruelty.

Modernity on endless trial

In Modernity on Endless Trial (1990), he argued that modern civilization carries within it an irresolvable tension: the desire for freedom and the longing for order. Neither could be eliminated, neither reconciled. “We are free to choose, but we are not free to abolish the consequences of our choices.” Liberty, he warned, is never secure; it must be defended against its own complacency.

Against relativism and fanaticism alike

Kołakowski rejected utopian absolutes but also pure relativism. “A culture of complete relativism,” he wrote, “prepares the ground for rule by force.” Without shared truths, politics dissolves into raw power. Yet when truths are absolutized, they justify despotism. His entire philosophy was a balancing act: defend moral standards, but distrust anyone who promises final salvation.

The role of myth and religion

In The Presence of Myth (1966) he argued that myths are not illusions to be discarded but essential frameworks of meaning. “To destroy myth is to destroy culture itself.” His later essays on God carried this further: even unbelief is haunted by transcendence. “The unforgettableness of God makes Him present, even in rejection” (God in a Godless Time). Religion, for Kołakowski, was not an answer but a reminder of limits—an antidote to the hubris of politics.

The paradox of values

In How to be a Conservative-Liberal-Socialist (1978), he argued that every society must embrace contradictory principles. Conservatism preserves continuity; liberalism guards rights; socialism fosters solidarity. None can be maximized without suppressing the others. “There is no happy ending in human history,” he concluded—only the perpetual balancing of competing goods.

The responsibility of intellectuals

He skewered those who justified tyranny for “progressive” ends. His retort to E. P. Thompson in an essay is exemplary: “If torture is evil in Brazil, it cannot be excused in Cuba. Either you condemn it everywhere, or you can condemn it nowhere.” His target was intellectual dishonesty—the selective outrage of thinkers who sacrificed truth to ideology. "I simply refuse to join people who show how their hearts are bleeding to death when they hear about any, big or minor (and rightly condemnable) injustice in the US and suddenly become wise historiosophists or cool rationalists when told about worse horrors of the new alternative society," Kolakowski observed.

Why He Matters

- A concrete influence. His writings nourished Poland’s opposition, provided intellectual scaffolding for Solidarity, and offered dissidents an alternative moral language. He bridged Western intellectual life and Eastern resistance.

- A prophet of limits. He warned that both utopia and nihilism are deadly: the first smothers freedom in the name of perfection, the second dissolves it in meaninglessness.

- A teacher of courage. Above all, he modeled how to admit error without cynicism. “To be human,” he wrote, “is to say: I was wrong.”

The Lesson for Today

Kołakowski’s conversion was not a leap from one dogma to another but a disciplined apprenticeship to doubt. His life stands against two temptations of our time: the dream of final solutions and the shrug of relativism. The task of politics, he insisted, is humbler: protect dignity, defend institutions of self-correction, and keep open the space where disagreement can survive.

“The world,” he wrote, “is not a machine to be remade, but a garden to be tended with care.” That garden is fragile. It cannot be engineered, only cultivated—patiently, humbly, and with the vigilance of jesters who refuse to let certainty harden into tyranny.

Kołakowski shattered utopia, but in doing so he kept alive the most precious thing of all: the restless, questioning spirit that sustains freedom.