‘Les Goûts Réunis’: How Baroque Rivalries Shaped a European Musical Tongue

Baroque music was fought over in courts, theatres, and pamphlets. Out of duels, diva feuds, and national quarrels arose les goûts réunis—a shared European musical language, cosmopolitan yet born of rivalry.

Between 1600 and 1750, Europe was a mosaic. The Peace of Westphalia (1648) confirmed the Holy Roman Empire as a patchwork of some 300 states. Italy was divided among duchies, papal territories, and independent republics; England reeled from civil war and restoration; France asserted absolutism under Louis XIV. Each court, each city, each patron cultivated its own traditions, jealous of rivals and eager to proclaim its cultural supremacy.

In this fractured world, music was never mere ornament. It was a language of power, devotion, persuasion, and identity. The new “Baroque style” that emerged around 1600 marked a decisive shift from Renaissance ideals of balance and cosmic order. Defined by the basso continuo, by contrast between solo and ensemble, by expressive dissonance and theatrical rhetoric, Baroque music sought above all to move the listener’s passions (affetti). To call something Baroque is to say that music had become drama: a field where competing visions of the world were staged in sound.

Baroque music was forged in rivalry.

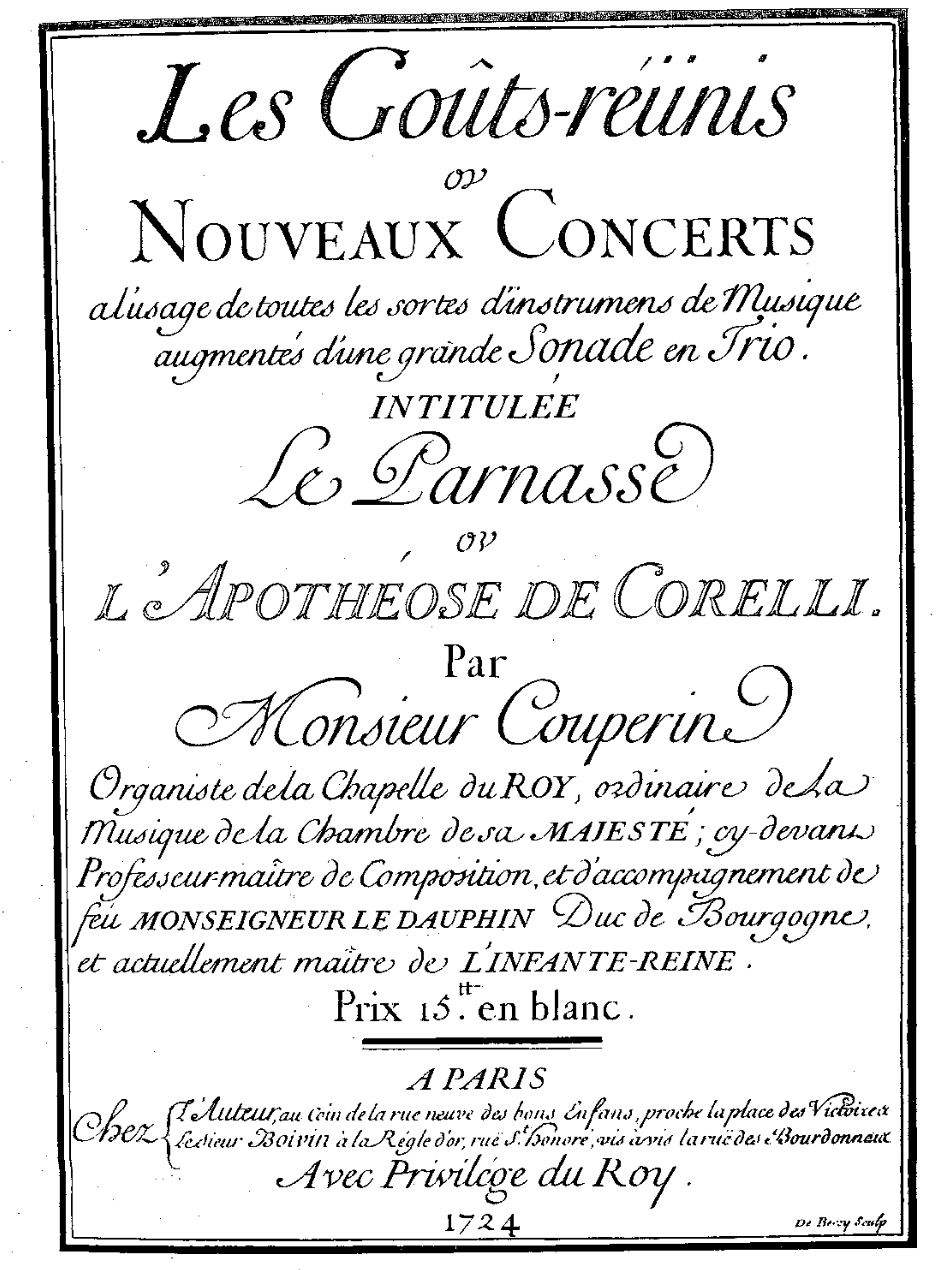

This essay follows a simple claim: Baroque music was forged in rivalry. Composers, singers, courts, and publics fought over style, meaning, and taste. Italy, France, Germany, and England each cultivated their own idioms, often in opposition to their neighbors. Yet by the early eighteenth century, those rivalries produced something paradoxical: a synthesis, what François Couperin in 1724 called les goûts réunis—the reunited tastes. Couperin’s collection gave the project its name, but he was far from alone.

Georg Philipp Telemann styled himself master of the “mixed taste,” combining French dances, Italian concertos, and even Polish folk idioms. Handel, moving from Halle to Rome to London, turned cosmopolitanism into career strategy, blending German counterpoint with Italian opera and the choral grandeur of England. Johann Sebastian Bach, though he rarely traveled, absorbed Europe through study and transcription, writing an Italian Concerto and a French Overture that proved he could inhabit both idioms, while his mature fugues welded national voices into unity. Even earlier, Arcangelo Corelli’s sonatas were praised across Europe as a model of balance, while Rameau’s Traité de l’harmonie sought universal theoretical foundations beneath national rivalries. Out of quarrel came not only accommodation but a common musical language: one of the first truly European cultural identities.

Out of quarrel came not only accommodation but a common musical language: one of the first truly European cultural identities.

The culture of contest and contrasts that animated Europe, was not abstract among musicians; it played out in theaters and courts. In London in 1727, the sopranos Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni loathed one another. During Bononcini’s Astianatte at the King’s Theatre, their feud erupted: insults turned to scratching and hair-pulling, while their aristocratic supporters brawled in the pit. Satirists portrayed the divas as cats and mocked Italian opera as a foreign absurdity. Handel, whose company had imported both women, saw his finances collapse. His solution was to abandon Italian opera and invent the English oratorio—choral, biblical, and native (Low, Handel’s Operas, 1970). Rivalry here was the crucible of creation.

In Paris in 1752, Pergolesi’s La serva padrona ignited the Querelle des Bouffons. Admirers like Rousseau praised its naturalness and wit; defenders of French tradition, led by Rameau, attacked it as vulgar Italian intrusion. Pamphlets poured forth, Voltaire and Diderot joined the fray, and the opera house became a battlefield over what it meant to be French (Charlton, Opera in the Age of Rousseau, 2012). Here rivalry was national identity itself.

Even Bach was not above the duel. In 1717 he traveled to Dresden, where he was scheduled to face the French virtuoso Louis Marchand in a harpsichord contest. The story goes that Marchand, daunted by Bach’s reputation, fled the city the night before. Whether apocryphal or not, the tale became allegory: German contrapuntal rigor triumphing over French elegance (Schulenberg, The Music of J. S. Bach, 1999). Rivalry here defined the stakes of craft and prestige in a Europe of competing courts.

Rivalry here defined the stakes of craft and prestige in a Europe of competing courts.

The Baroque revolution began in Florence. The Camerata, a circle of humanists, sought to revive the spirit of Greek tragedy. Their invention of monody—a single expressive voice supported by basso continuo—challenged the dense polyphony of the Renaissance. Giulio Caccini’s Le nuove musiche (1602) declared music’s new purpose: to move the passions. Giovanni Maria Artusi protested, accusing Claudio Monteverdi of crude dissonances. Monteverdi’s riposte—his doctrine of the seconda pratica—redefined music as rhetoric, words as “mistress of the harmony.”

The quarrel was not trivial. It was about whether music existed to mirror divine order or to embody human emotion. Out of it came opera itself.

The quarrel was not trivial. It was about whether music existed to mirror divine order or to embody human emotion. Out of it came opera itself. Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607) demonstrated how recitative, aria, and chorus could dramatize myth while serving courtly politics. Later, in Rome, Corelli codified the concerto grosso, while in Venice Vivaldi battled rivals in the opera houses and responded to pamphleteers who called him unfit for the priesthood because of his theatrical career (Talbot, Vivaldi, 2000). Rivalry, far from a distraction, propelled innovation. Italian music’s expressive fire, its virtuosity and rhetoric, became Europe’s most exportable style.

If Italy invented, France codified. At Versailles, Louis XIV turned art into ritual, and Jean-Baptiste Lully enforced discipline with a rod of iron. His French overture, with its dotted rhythms, became the sound of royal entrance. He imposed uniform bowing on the Vingt-quatre Violons du Roi, making the orchestra itself a symbol of order. But even in France, order provoked contest. When Rameau premiered Hippolyte et Aricie in 1733, audiences were stunned by its harmonic daring. The Querelle des Lullistes et des Ramistes raged for years, pamphlets denouncing Rameau’s music as “baroque”—then a term of abuse, meaning bizarre and deformed (Sadler, The Rameau Compendium, 2014). To defend Lully was to defend tradition; to embrace Rameau was to open French identity to Italian influence.

To defend Lully was to defend tradition; to embrace Rameau was to open French identity to Italian influence.

Later, the Querelle des Bouffons reignited the conflict. What was at stake was not only music but philosophy: centralization vs. cosmopolitanism, absolutist grandeur vs. Enlightenment naturalness. French Baroque music was thus inseparable from politics—it was rivalry transposed into sound.

The German-speaking lands were the most fragmented of all. Dozens of small courts, free cities, and churches vied for prestige. Heinrich Schütz, trained in Venice, imported Italian drama to Dresden, while Lutheran chorales gave composers a common treasury of melodies. In Hamburg, the opera house founded in 1678 competed with sacred music for audiences, staging biblical plots with theatrical flair. Organists, too, fought for renown. Dieterich Buxtehude’s Abendmusiken in Lübeck were so famous that young musicians traveled for days to hear them. Bach himself walked 250 miles from Arnstadt, overstayed his leave, and returned in disgrace—proof of how high the stakes of musical rivalry could be.

For Bach, counterpoint itself was a form of contest. His fugues pit subject against countersubject, voice against voice, until dissonance resolves into higher order. The legend of his duel with Marchand crystallized what German musicians believed: their music’s intellectual rigor was not parochial but universal, able to absorb and outdo Italian and French models. Rivalry, here, became synthesis.

England’s story was shaped less by courts than by commerce. After the turmoil of the Civil War, music revived with the Restoration stage. Henry Purcell wrote semi-operas like King Arthur, where spoken drama alternated with masque. His “Frost Scene” and “Dido’s Lament” combined English theatrical wit with Italian lament-bass traditions. But the fiercest rivalry came later, when Handel brought Italian opera seria to London. For decades he dominated the stage—until satire struck. John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera (1728) mocked Italian opera with thieves, prostitutes, and popular ballads. Its runaway success nearly bankrupted Handel. The city split between high-flown Italian spectacle and vernacular parody (Weber, The Great Transformation of Musical Taste, 2008).

Handel’s answer was the oratorio. With Saul (1739), Israel in Egypt (1739), and Messiah (1741), he fused Italian lyricism, German counterpoint, and English choral tradition into a new national form. Rivalry here was commercial—foreign import vs. domestic satire—and its resolution gave England a musical voice of its own.

By the early eighteenth century, these rivalries had prepared the ground for reconciliation.

By the early eighteenth century, these rivalries had prepared the ground for reconciliation. François Couperin declared the project in 1724 with Les Goûts Réunis, explicitly blending Italian fire with French grace. Telemann styled himself master of the “mixed taste,” writing quartets that fused French instrumentation, Italian virtuosity, and even Polish folk idioms. Handel’s Concerti Grossi Op. 6 combined Corelli’s model, French overtures, and English dances. Bach, without leaving Saxony, absorbed all Europe through study and transcription, turning national dialects into universal language.

This was not eclecticism but integration. Out of duels, pamphlet wars, and theatrical riots came a “common practice”: tonal harmony, shared forms, standardized genres. By mid-century, Europe spoke a single musical language—one that Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven would inherit.

The Baroque shows us that harmony is born of discord. [...] The quarrels forced clarity, sharpened styles, and drove composers to new invention.

The Baroque shows us that harmony is born of discord. Rivalries were everywhere—singers clawing each other on stage, pamphleteers attacking “foreign” styles, composers dueling at the keyboard. Yet the outcome was not chaos but unity. The quarrels forced clarity, sharpened styles, and drove composers to new invention.

Couperin’s phrase les goûts réunis captures the paradox: the very fragmentation of Europe produced its first shared cultural language. In an age of dynastic wars and confessional divides, music became the field where difference was not erased but transfigured. Like a fugue, Baroque Europe was many voices, independent yet bound together.

Couperin’s phrase les goûts réunis captures the paradox: the very fragmentation of Europe produced its first shared cultural language. In an age of dynastic wars and confessional divides, music became the field where difference was not erased but transfigured.

The lesson is not only historical. Our own age, too, is tempted to see rivalry as threat. The Baroque reminds us that contention can be the condition of concord—that true harmony is never uniform, but a contrapuntal journey.

The lesson is not only historical. Our own age, too, is tempted to see rivalry as threat. The Baroque reminds us that contention can be the condition of concord—that true harmony is never uniform, but a contrapuntal journey.

Excerpt from the text

1. Rival Tastes: The Republic of Music

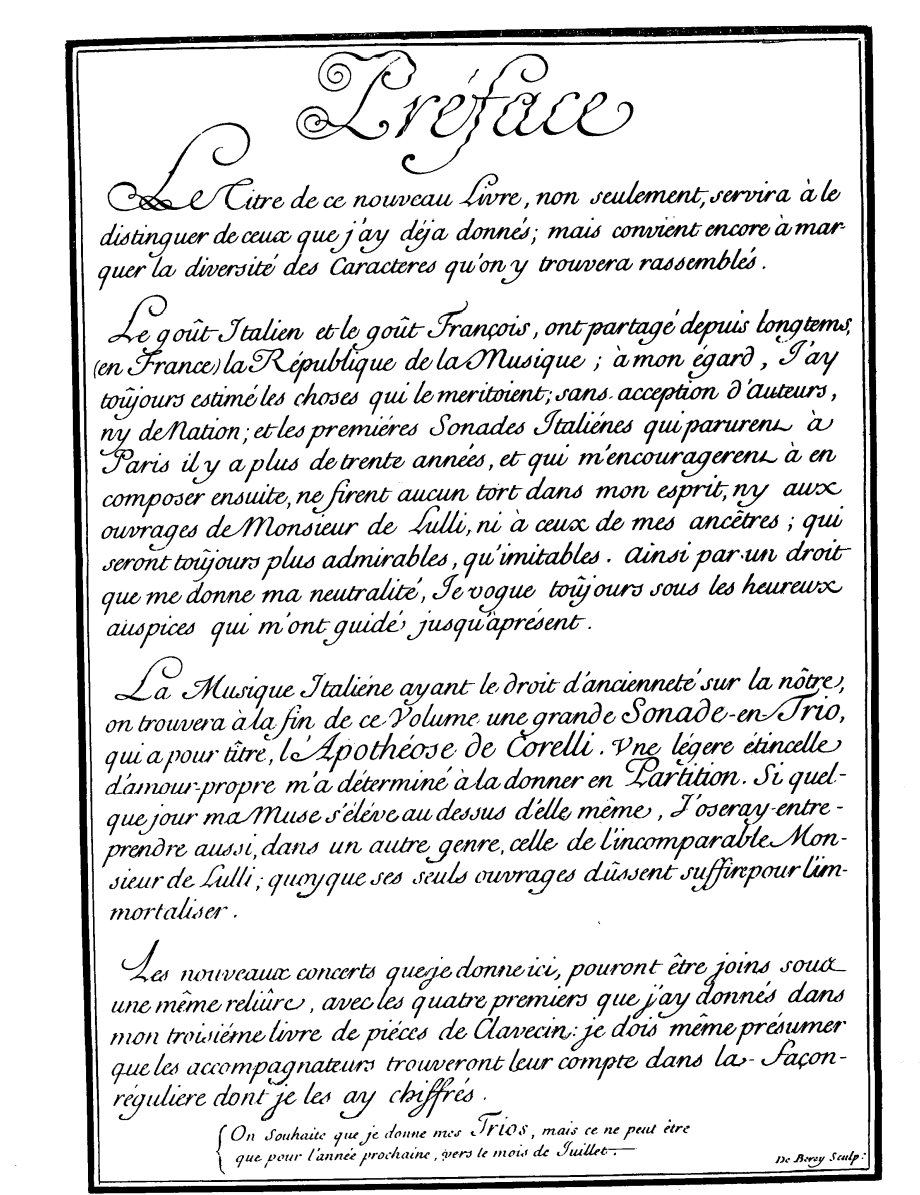

“Le goût Italien et le goût François ont partagé depuis longtems en France la République de la Musique; à mon égard, j’ay toujours estimé les choses qui le méritoient, sans acception d’auteurs ny de Nation.”

(“The Italian taste and the French taste have long divided the Republic of Music in France; for my part, I have always esteemed what deserved esteem, without regard to author or nation.”)

2. Neutrality as Principle

“…ainsi par un droit que me donne ma neutralité, je voguë toujours sous les heureux auspices qui m’ont guidé jusqu’à présent.”

(“Thus, by a right granted me by my neutrality, I continue to sail under the happy auspices that have guided me thus far.”)

3. Apotheoses of Corelli and Lully

“La Musique Italienne ayant le droit d’ancienneté sur la nôtre, on trouvera à la fin de ce Volume une grande Sonade en Trio, qui a pour titre l’Apothéose de Corelli… Si quelque jour ma Muse s’élève au-dessus d’elle-même, j’oseray entreprendre aussi… celle de l’incomparable Monsieur de Lully.”

(“As Italian music has seniority over our own, at the end of this volume one will find a great trio sonata entitled The Apotheosis of Corelli… If ever my Muse rises above herself, I will also dare to attempt one for the incomparable Monsieur de Lully.”)