In Defense of a Populist Interruption

Populism, wrote Christopher Lasch, is less a doctrine than a rebellion of the scorned. Trump’s rise was not ideology but interruption: a voice for the forgotten, exposing brittle elites and forcing America to confront its distance from its own people.

Populism, observed American historian Christopher Lasch, is less a doctrine than a rebellion of those whom elites have scorned. In The Revolt of the Elites (1995), he warned that a “new aristocracy of professional managers” had become rootless, contemptuous of national traditions, and dismissive of ordinary people: “The new elites, the professional classes in particular, regard the masses with mingled scorn and apprehension.” Unlike earlier elites, who carried obligations of stewardship, this new class sought liberation—from duty, from history, from the very idea of place. The rise of Donald Trump was, in this sense, the revolt not of an ideology but of the forgotten.

Unlike earlier elites, who carried obligations of stewardship, this new class sought liberation—from duty, from history, from the very idea of place. The rise of Donald Trump was, in this sense, the revolt not of an ideology but of the forgotten.

Since 2016, Trump has been treated as calamity. To liberal elites, he was a grotesque interloper, a threat to institutions, a barbarian at the gates. Yet this metaphor, endlessly repeated, revealed more about the citadel than the supposed barbarian. A fortress requires a moat; and America’s political class had encircled itself with jargon, credentialism, and moral self-regard, convinced it could legislate without listening. The shock of Trump was not merely that he broke through, but that his breach revealed how high—and how brittle—the walls had become.

Trump’s genius, if one may call it that, was not ideological but visceral. He spoke plainly. He said the forbidden aloud. And in so doing, he made millions feel visible again. To the arbiters of taste, his language was proof of barbarism: crude slogans, half-sentences, improvisations. Yet this very speech was the scandal of truth. George Orwell diagnosed political language as “designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind” (Politics and the English Language, 1946). Trump’s diction was the opposite: unfiltered, direct, often raw, but incapable of the pious evasions that dominate professional politics. When he said “the system is rigged,” people believed him—not because he was eloquent, but because they already felt it.

There was also something undeniably democratic in Trump’s resilience. However fierce the assaults, he endured.

There was also something undeniably democratic in Trump’s resilience. However fierce the assaults, he endured. Ortega y Gasset once wrote, “The health of democracies, of whatever type and range, depends on a wretched technical detail: their being avoided by the masses at certain times” (The Revolt of the Masses, 1930). Trump inverted the point: he drew the masses in, not to manage but to energize them. What critics dismissed as circus was in fact recognition. His rallies were not about policy minutiae but about presence, the theater of being seen.

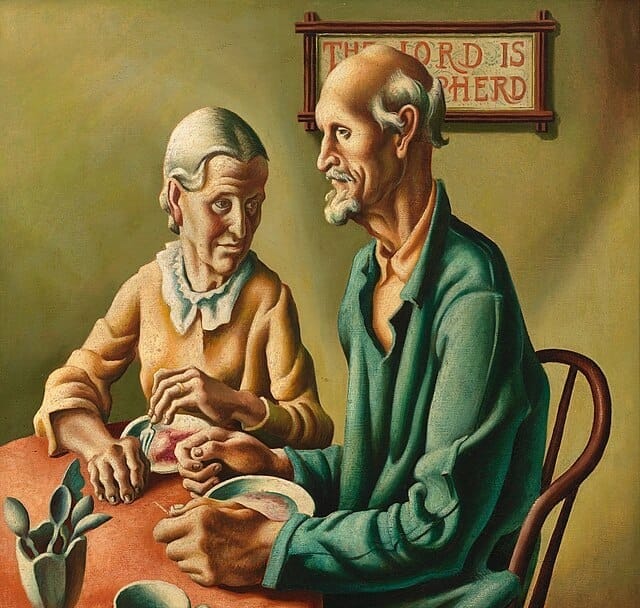

Alexis de Tocqueville saw in democracy an irrepressible drive toward equality, but also a fragility: institutions lose legitimacy when they grow too distant from the governed. Pierre Manent sharpened the point: “The people need to feel that the government is theirs, not something foreign to them” (A World beyond Politics?, 2006). Trump’s rallies, gave this closeness back. Critics sneered at the red hats and chants, but the sneer was itself the problem.

Populism is not gentle. It is a fever. It inflames, exaggerates, destabilizes. Tocqueville feared its excesses, and at time the platform embodied some of them. Yet to call populism a disease is to mistake symptom for cause. The deeper illness was elite withdrawal: the conviction that democracy could be managed by experts while ordinary citizens were pacified with slogans of “progress.” Trump shattered that illusion.

The deeper illness was elite withdrawal: the conviction that democracy could be managed by experts while ordinary citizens were pacified with slogans of “progress.” Trump shattered that illusion.

Isaiah Berlin, in “Two Concepts of Liberty” (1958), reminded us that politics always entails conflict between ultimate values: “The necessity of choosing between absolute claims is then an inescapable characteristic of the human condition.” Trump was precisely such a choice: to endure disruption, coarseness, and risk in order to avert a greater loss—the quiet death of representation.

Raymond Aron once observed, “Political freedom is a regime in which the ruled can change their rulers without bloodshed” (Democracy and Totalitarianism, 1965). Trump, in his own way, kept that truth alive. For all the accusations of authoritarianism, he submitted to the verdict of elections, and his return to politics in 2024 was not through a coup but through persuasion of the electorate. That resilience, however jarring, is itself a testament to democracy’s strange strength.

His [Trump's] gift, unwelcome though it is to cultivated opinion, was to remind the republic that sovereignty lies not in think tanks, media towers, or Silicon Valley campuses, but in the rough hands of its citizens.

Trump is no philosopher-king. But he was, and remains, an interruption—and interruptions are sometimes the only way democracies remember themselves. His gift, unwelcome though it is to cultivated opinion, was to remind the republic that sovereignty lies not in think tanks, media towers, or Silicon Valley campuses, but in the rough hands of its citizens. The story of Trump is less about one man than about the people he revealed: the forgotten, the disdained, the unfashionable millions who will not be ruled as abstractions. To dismiss them, or him, as merely deplorable, is to invite the decay of liberty itself. For all his flaws, Trump forced America to look in the mirror. Perhaps some did not like the reflection. But it was true. ◳ [GC]