Icons Against Power: Andrei Rublev

Amid ruins and censors, Rublev painted communion. Tarkovsky filmed his silence. Across centuries, both remind us: beauty does not erase suffering, but transfigures it—conscience’s last word against power.

From Mongol raids to Brezhnev’s censors, a 15th century Russian monk serene vision of communion (and Tarkovsky’s cinema) reveal how beauty and conscience outlast violence and ideology. Enduring acts of defiance are forged by the quiet persistence of faith and art.

At Cannes in 1969, Andrei Rublev unspooled at four o’clock in the morning on the festival’s final day, a scheduling maneuver meant to bury a troublesome Soviet import. It failed. Even at that haunted hour, critics recognized a major event and awarded the International Critics’ Prize. Back in Moscow, the film had been trimmed, shelved, and shown only once under police guard; Brezhnev himself is said to have walked out of a private projection. Only in 1971 did the authorities relent, and only after Paris exhibitors defied Soviet protests and screened it abroad.

Why the anxiety? Tarkovsky’s film was no agitprop but an episodic meditation on a medieval icon painter’s conscience. In refusing to harness art to ideology—in treating Christianity as an axiom of Russia’s past and the artist as a figure of world-historical conscience—the film subverted a state that demanded obedience from images.

The irony, surely not lost on Tarkovsky, is that the monk he portrays as struggling under princely and clerical pressure later became the official measure of orthodoxy. A century after Rublev’s death, the Stoglav Council of 1551 declared that all icons in Russia must be painted “as Andrei Rublev painted”—an extraordinary decision that canonized not only his work but his style as timeless authority. Centuries later, in 1988, the Church canonized Rublev himself during the millennium celebrations of Russian Christianity. And the film that Soviet censors once tried to bury at 4 a.m. has since been enshrined as a cultural monument. Institutions that once distrusted Rublev ultimately made him their standard.

Andrei Rublev (c. 1360–1430) lived and painted in one of the most violent centuries of Russian history. The Mongol khans of the Golden Horde extracted heavy tribute and launched raids that could reduce entire towns and monasteries to ash. Rival princes fought one another for power, often calling on foreign armies to aid their cause. Repeated waves of famine and plague decimated the population. Violence was not exceptional—it was the backdrop of life.

“To paint serenity in an age of cruelty was not indulgence but defiance.”

In this fractured world, monasteries became more than houses of prayer. They were centers of literacy, treasuries of culture, and, at times, moral counterweights to politics. St. Sergius of Radonezh, founder of the Trinity Monastery near Moscow, taught that contemplation of the Trinity could “conquer the hateful fear of this world’s dissensions.” This was not escapist mysticism but a theological antidote to despair. It was within Sergius’s community that Rublev was formed as monk and painter.

This was not escapist mysticism but a theological antidote to despair and disunity.

Rublev’s life is only faintly recorded. In 1405 he apprenticed under Theophanes the Greek, a Byzantine master whose icons were dramatic and severe, full of divine judgment. In 1408 he worked on frescoes at the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir. By the 1420s he was painting for the rebuilt Trinity Cathedral of Sergius’s monastery, and later resided at the Andronikov Monastery in Moscow, where he died. The details are sparse, but the art makes its own argument: Rublev crystallized a world of fracture into images of serenity and communion.

His masterpiece, the Old Testament Trinity, embodies that vocation. Earlier icons of the “Hospitality of Abraham” depicted Abraham and Sarah serving three angelic visitors. Rublev eliminated the human hosts, leaving only the angels around a table, shifting the focus to a direct contemplation of divine life itself.

The work’s innovations give it distinctive power. The angels’ gestures and gazes form a hidden circle, a visual theology of perichoresis—the mutual indwelling of the divine persons. At the center of the table stands a solitary chalice: Eucharistic symbol, sacrificial offering, and invitation—a table set for participation. As scholar Priscilla Hunt has argued, the icon’s symbolic economy draws on hesychast spirituality and the Dionysian tradition: “Wisdom builds her house… offers her feast.” The angels’ circular harmony images divine unity; the chalice signifies sacrifice as the foundation of communion; the open space at the front of the table deliberately welcomes the viewer. In Hunt’s words, “all is embodied oneness, both the word and the silence of God.”

Rublev crystallized a world of fracture into images of serenity and communion.

The context makes the serenity more striking. In December 1408, Emir Edigey of the Golden Horde torched the Trinity Monastery, only months after Rublev had painted frescoes in Vladimir. A seventeenth-century tale later claimed that the Trinity was painted to “counter the enmities of the world.” Whether or not the story is literal, its meaning is clear: Rublev’s serenity was not naïve but acquired—an image of communion set against fire and fear.

The most vivid portrait of Rublev today does not come from medieval chronicles but from Tarkovsky’s imagination. His Andrei Rublev (1966) is neither strict biography nor pure invention. Immersed in medieval sources yet unafraid to depart from them, Tarkovsky created a meditation on what it means for an artist to remain faithful amid violence. In doing so, he inevitably romanticized Rublev, turning a shadowy historical monk into an archetype of artistic conscience.

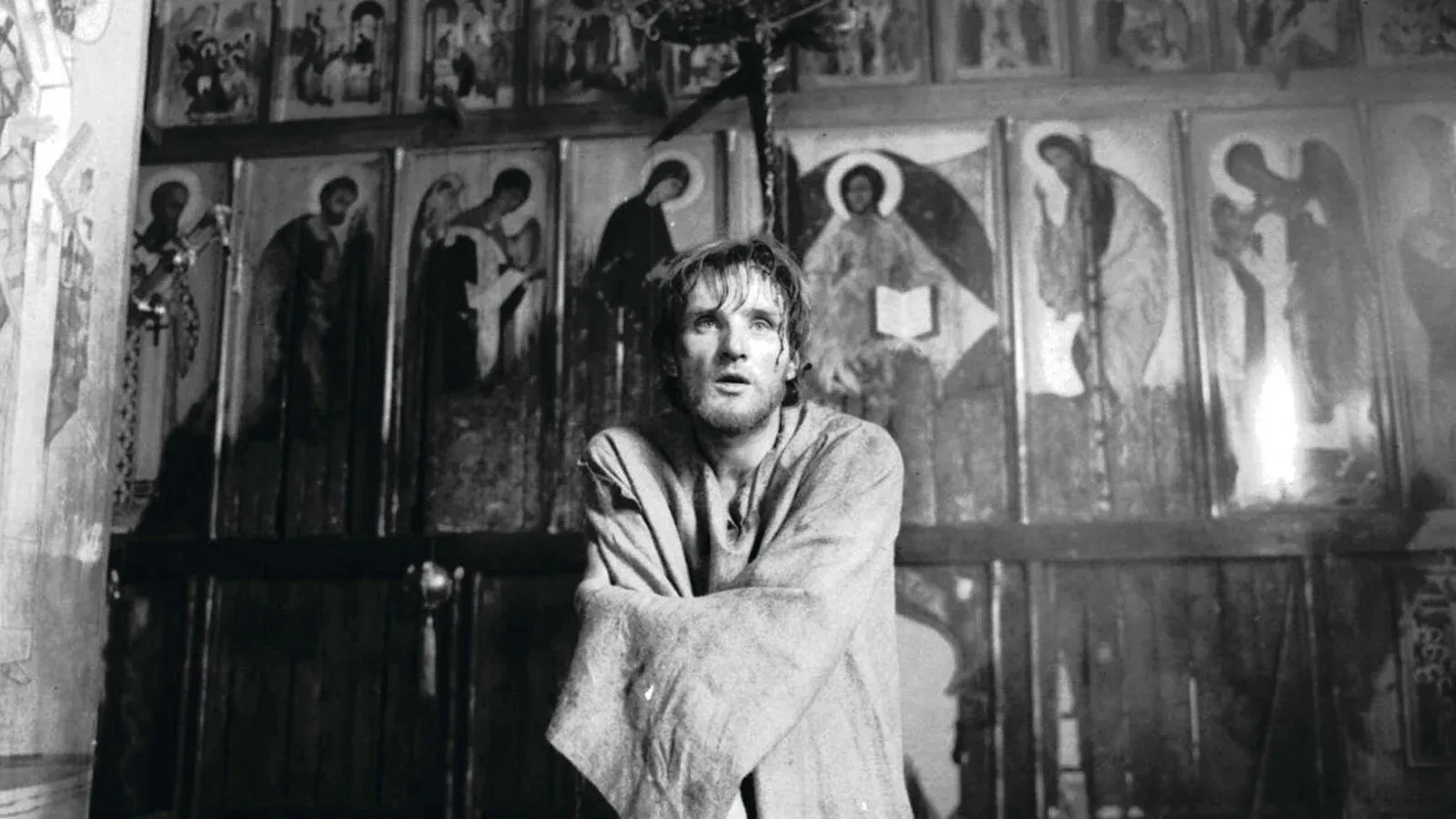

The film’s most searing episodes—the denunciation of a jester, the sack of Vladimir by Tatar raiders, the blinding of stonemasons at a prince’s command—are staged not to shock but to expose the brutal cost of power in a world perpetually at war with itself. Against this backdrop, Rublev refuses to paint a Last Judgment meant to terrify the faithful. Later, after killing a man to protect a young woman, he withdraws into silence, embodying a conscience that would rather be mute than complicit.

Tarkovsky’s wager was that such freedom of conscience could be filmed. His camera does not explain; it witnesses. Long takes of rain, fire, and mud insist on the world’s physicality. The prologue’s failed Icarus suggests the peril of ambition. In the climactic “Bell” episode, a boy bluffs knowledge of bell-casting and, through courage and communal labor, succeeds. Watching this triumph, Rublev breaks his silence: “You’ll cast bells and I’ll paint icons.”

“After hours of monochrome carnage, the epilogue bursts into color: Rublev’s icons, luminous and calm, as if the film’s battered world were at last redeemed by vision.”

The final revelation of the icons transfigures what came before: violence answered not with judgment but with serenity. Yet the film is not history. Chronology is compressed, episodes invented, the artist’s conscience foregrounded over archival certainty. Tarkovsky admitted as much: “What they did not like… was not the ideas, but the artistic form: the mere fact that a phenomenon called ‘art’ may exist at all.”

Rublev’s art was not ornament but ethic. In a century of raids and burnings, he painted communion. In a culture trained to punish, he painted mercy. His icons became public argument as much as private devotion.

Tarkovsky’s romanticized film, censored and delayed, made modern audiences feel the cost of such serenity. The bell pealed, the vow broke, the icons glowed into color. At Cannes in 1969, even at four in the morning, critics recognized what censors could not extinguish. We should recognize it again: beauty and art, even in war, is conscience’s last word.

We should recognize it again: beauty and art, even in war, is conscience’s last word.

Postscriptum: Tarkovsky's father - the poet - on seeing the world without Malice

The essay began in a world of raids and censorship; it ends with a vision of beauty that outlasts both. Rublev’s icons and Tarkovsky’s film are separated by five centuries, yet they converge on the same ethic: art does not silence suffering, it transfigures it. Arseny Tarkovsky, the director’s father and one of Russia’s great twentieth-century poets, gave voice to this ethic in his wartime poem Life, Life (1945):

And I rejoiced in earthly blessings,

In the breath of spring, in the hum of bees.

But the greatest gift was this:

To see the world with eyes unclouded by malice,

To live, to think, to feel, to love,

To recognize the miracle of being—

And to know that all of this is life, and only once.

These lines could serve as Rublev’s own credo. His Trinity does not deny violence; it refuses to let violence cloud the vision of communion. The icon’s open table and serene figures invite us into a way of seeing that holds difference in love rather than in fear. Tarkovsky’s cinema, shaped by his father’s poetry, inherits the same vocation. His camera lingers on rain, mud, and fire, not to brutalize the viewer but to educate attention—to show that even in cruelty, the world can still be seen without malice.

States rise and fall, censorship silences and recedes, raids burn and pass into chronicles. What remains are images and words that teach us how to see—steadily, unclouded, and with conscience intact.

Lessons from Rublev and Tarkovsky

1. Beauty as a civic ethic.

Rublev’s Trinity is not just a theological image but a social proposition. Its circle of angels models equality without domination, an order of harmony that politics could not achieve. In times of violence, beauty becomes more than consolation—it becomes a blueprint for community.

2. Conscience as resistance.

When Rublev refuses to paint a Last Judgment meant to terrify, or falls silent rather than sanction violence, he asserts that art must not be an accomplice to fear. Tarkovsky dramatizes that refusal, turning Rublev’s conscience into a parable for modern audiences. In both cases, silence is not withdrawal but resistance.

3. Tradition as creative freedom.

Rublev did not break iconographic canons; he reoriented them. By removing Abraham and Sarah, centering the chalice, and binding the angels in a circle, he gave Orthodoxy’s visual tradition a new theological depth. Fidelity, paradoxically, became the condition of freedom.

4. Witness, not propaganda.

Tarkovsky’s film refuses slogans. Long takes of rain, mud, and fire do not argue; they testify. Viewers are asked not to consume but to witness. In a political culture built on propaganda, such patient witnessing was itself subversive.

5. Art as endurance.

From the raids of Emir Edigey to Soviet censors, Rublev’s icons and Tarkovsky’s film survived forces determined to erase or distort them. Their survival suggests that art endures not by power but by persistence—carried forward in memory, reverence, and the stubborn need to see beyond violence.