Has Polarization Become 'Infrastructure'? Seven Layers of Division

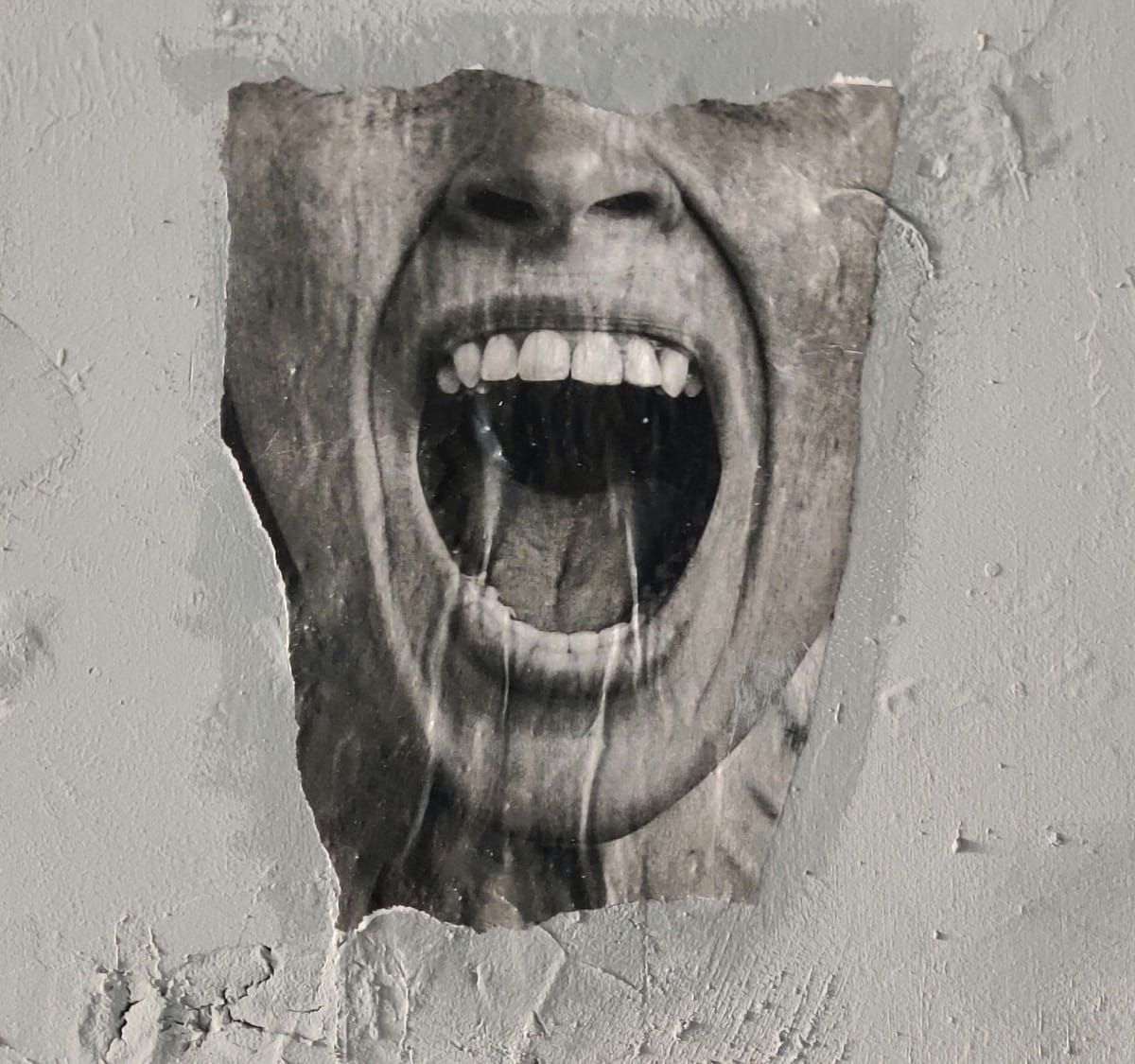

Polarization is no longer just emotion or bias—it’s infrastructure. Built from attention, technology, and incentive, it sustains division by design. Understanding its machinery is the first step toward rebuilding the architecture of pluralism.

Polarization is a defining paradox of our time: everyone deplores it, yet no one escapes it. Voters say they are exhausted by partisanship, institutions lament the loss of trust — all while the mechanics of division continue to hum beneath the surface.

Here we propose a diagnosis. Polarization is no longer just a mood, bias, or moral failing. It has become infrastructure — a set of interlocking systems that channel emotion, cognition, and belonging toward conflict. Like roads or power grids, these systems are built by human choices, but once built, they shape our behavior, creating a self-sustaining equilibrium of antagonism.

The silver lining is that to see polarization as infrastructure is to reclaim agency and moral responsibility. It allows us to move from denunciation to design — to ask how we might rebuild the civic architecture of pluralism for flourishing democracies rather than simply curse its decay.

Over the past forty years, affective polarization—the degree to which citizens feel dislike or distrust toward members of the opposing political camp—has deepened across nearly all established democracies. Yet the trajectory is uneven. As Levi Boxell, Matthew Gentzkow, and Jesse Shapiro show in their cross-country analysis Cross-Country Trends in Affective Polarization (2024), the United States has experienced by far the most dramatic surge. Between 1978 and 2020, Americans’ “feeling thermometer” gap between their own party and the opposing party more than doubled—from roughly 27 to 56 points. By contrast, polarization in most European democracies, as well as in Canada, Denmark, and Australia, has remained comparatively moderate, and in some cases even declined slightly.

The striking discovery, however, is that the curve has flattened almost everywhere. Across twelve OECD nations, affective polarization has stabilized at a high plateau: intense, durable, and resistant to both reform and fatigue. The U.S. stands as the outlier in magnitude but not in pattern. Whether in Washington, Paris, or London, division has ceased to accelerate; it has become a steady equilibrium—a civic condition that feels feverish yet self-sustaining.

What defines this equilibrium is not only widening ideological distance, but affective distortion: citizens systematically exaggerate how extreme their opponents are, misreading modest disagreement as existential conflict. The political center has not disappeared so much as it has been drowned out by the volume of mutual hostility. As Boxell and his colleagues observe, people in polarized societies increasingly hold “mirror-image misperceptions,” imagining the other side as more radical and malevolent than it is.

What defines this equilibrium is not only widening ideological distance, but affective distortion: citizens systematically exaggerate how extreme their opponents are, misreading modest disagreement as existential conflict.

For the United States, this dynamic is especially corrosive. The world’s oldest continuous democracy now functions under a permanent climate of mutual suspicion. Outrage has become chronic but not terminal, as mistrust endures even as most Americans profess exhaustion with it.

The central puzzle, then, is no longer why polarization erupted, but why it persists. Why have the fires of division not burned out? Why does civic fatigue not yield moderation? The answer we are attempting to provide lies not in temperament or cognition alone but in structures. Division now operates as a system—a vast machinery of attention, identity, and technology that adapts to reform and reproduces its own demand. That is key to understand polarization today - what once seemed an episodic political passion has hardened into infrastructure: an architecture of conflict built into daily routines.

Most theories of polarization fall into two camps. Psychological models focus on biases, including confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, identity-protective cognition. On the other hand, institutional models emphasize incentives: party competition, media ecosystems, elite manipulation.

Each is true but incomplete. The infrastructure model bridges them. Infrastructures are built by human beings (agency), but once established, they constrain and channel behavior (structure). They are maintained, adapted, and reproduced — just like polarization.

This reframing adds explanatory depth: polarization persists not because citizens or elites consciously will it, but because they inhabit systems that make it profitable, habitual, and emotionally rewarding.

The new approach also creates space for moral and civic reflection. “Infrastructure” invites questions of repair and design — not just blame. It points to the missing dimension of democratic policy: the moral architecture of political pluralism, essential to enable the Arendtian "action" in a "vita activa" (The Human Condition, 1958).

Through comparative research and synthesis across political psychology, communications, and moral philosophy, we identified seven interlocking layers that together form the infrastructure of polarization. They are not hierarchical but ecological: each layer feeds the others, producing a feedback system that converts bias into outrage, outrage into visibility, visibility into influence, and influence back into belief. Polarization, in this sense, is not only a failure of civility; it is a designed equilibrium. It organizes emotion, attention, and belonging into a structure that is remarkably resistant to fatigue. The seven infrastructures are:

- cognitive (mind),

- affective (emotion),

- technological (platform),

- institutional (incentive),

- social (relation),

- epistemic (truth), and

- moral-spiritual (meaning).

1. Cognitive Infrastructure — the mental circuitry

At the core of polarization lies a flaw in the mind’s design: our limited tolerance for complexity. Humans are cognitive misers—we conserve mental energy by seeking shortcuts to coherence. The mechanisms are multiple: confirmation bias keeps us loyal to information that flatters our preconceptions; motivated reasoning turns disagreement into moral drama; tribal cognition filters facts through the prism of belonging. Digital life magnifies these ancient reflexes. What once required deliberation is now instantaneous; what once felt like thought now feels like impulse. Social media’s architecture rewards speed over reflection, emotion over accuracy. In that accelerated environment, the mind’s defensive habits become its default operating system. Intellectual difference begins to feel like moral threat.

The result is a world of mirror-image misperceptions: each side inhabits a distorted reflection of the other. When progressives encounter calls to “protect traditional values,” many imagine the rise of Christian nationalism; when conservatives see inclusive school policies, they imagine ideological indoctrination. The same language—of rights, family, and freedom—means radically different things depending on which moral tribe speaks it. During the 2020–2021 crises, these perceptual filters hardened. To many on the left, the phrase “Stop the Steal” became shorthand for democratic decay; to many on the right, “Defund the Police” symbolized moral anarchy. In both cases, small activist fringes were taken to represent the whole. Each camp saw in the other not citizens with divergent concerns, but an existential caricature.

This is what Yale scholar Dan Kahan calls identity-protective cognition: the mind’s instinct to defend the tribe even at the cost of truth. The infrastructure of polarization is built here—in the neural circuitry that mistakes predominant beliefs for being right.

2. Affective Infrastructure — the emotional current

Polarization feeds not on ideas but on emotion. Its lifeblood is arousal. In an economy where attention is currency, emotion becomes power. Political entrepreneurs have long known this. It is easier to mobilize disgust than curiosity, easier to sell anger than ambiguity. As Jonathan Haidt observes in his moral foundations theory, moral judgment begins in the gut and only later recruits reason for its defense. We feel first, then rationalize. The affective infrastructure of democracy thus resembles a power grid—largely unseen yet constantly humming, converting raw emotion into civic voltage.

Since the 1990s, entire industries have learned to tap that current. Talk radio hosts turned indignation into identity long before Twitter learned to weaponize it. Cable news built a business model around perpetual alarm: the word BREAKING flashes even when nothing is breaking. Social media merely automated the same principle—what researchers call rage-bait—where emotional intensity, not factual accuracy, determines reach. Each side has its own emotional vernacular. On the right, outrage over immigration or “cancel culture” affirms solidarity through shared resentment; on the left, moral shock at inequality or perceived bigotry performs a similar unifying role. The passions differ, but their circuitry is identical: anger is the price of belonging.

The passions differ, but their circuitry is identical: anger is the price of belonging.

The result is an emotional arms race in which moderation feels tepid and empathy suspect. Polarization, in this sense, is not merely a clash of beliefs—it is an addiction to the feelings that make belief possible.

3. Platform Infrastructure — the technological delivery system

Technology supplies the bloodstream through which polarization circulates. Platforms rank content by engagement, and engagement, in practice, means outrage. Virality becomes the new visibility. Every user is now a micro-broadcaster. What began as a democratization of speech has evolved into what sociologist Zeynep Tufekci calls an architecture of amplification: a system that rewards emotional extremity because that is what keeps us scrolling.

Empirical studies confirm the pattern. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, researchers at Mozilla found, has repeatedly nudged users toward more sensational or conspiratorial content—sometimes after only a few clicks. Facebook’s own internal memos, disclosed by whistleblower Frances Haugen in 2021, admitted that engagement-driven ranking “exacerbates divisiveness” but warned that dialing it down would reduce time on site. Even Twitter’s (now X’s) algorithmic feed, engineers reported in 2023, systematically boosts posts with high emotional valence—especially anger and moral condemnation—across both political camps.

The incentives are symmetric but not neutral. [...]Both become performers in the same marketplace of moral emotion.

The incentives are symmetric but not neutral. The right’s influencers learn that fury at “wokeness” drives traffic; the left’s activists discover that indignation at injustice does the same. Both become performers in the same marketplace of moral emotion. The system does not care who wins—only that the contest never ends. Polarization, in this sense, it is built into the plumbing of our digital commons, a delivery system of division that converts every human impulse—fear, belonging, righteousness—into data, and then into profit.

4. Institutional Infrastructure — the incentive structure

Political and cultural institutions have learned to monetize division. Polarization is no longer a byproduct of democracy’s friction; it is a business model. The institutions once designed to mediate conflict sometimes feed on it. Political parties have become fundraising machines for outrage. Campaigns test which phrases—“stolen elections,” “war on women,” “defend our freedom”—most effectively spark indignation and dollars. News organizations, competing in a saturated market, have likewise discovered that fear and confirmation sell better than nuance. The moderate voice, which once conferred credibility, now risks irrelevance.

Universities and advocacy groups, too, have drifted toward ideological branding. Departments and NGOs increasingly adopt the moral vocabulary of their constituencies, rewarding performative certainty over intellectual risk. As the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu might note, moral capital now functions as symbolic capital: to dissent is to jeopardize belonging. The result is an institutional feedback loop. Political parties polarize to mobilize; media dramatizes to monetize; academia moralizes to legitimize. Each depends on the other’s excess to sustain its own.

The result is an institutional feedback loop. Political parties polarize to mobilize; media dramatizes to monetize; academia moralizes to legitimize. Each depends on the other’s excess to sustain its own.

As Raymond Aron warned that fanaticism is the perversion of conviction (The Opium of the Intellectuals, 1955). That perversion has become systemic. Institutions once built to arbitrate difference now perform it theatrically for audiences who demand purity. Consider the reciprocal outrage economy of U.S. cable news. Fox News and MSNBC thrive by constructing mirror-image moral dramas—each presenting itself as the last bastion against the other’s imagined tyranny. Ratings spike when the nation convulses. Meanwhile, bipartisan bills on infrastructure, opioids, or veterans’ care rarely make prime time. The machinery of outrage, having become profitable, cannot easily be dismantled.

The institutional infrastructure of polarization thus binds principle to performance. It rewards those who amplify discord and punishes those who attempt repair.

5. Social Infrastructure — the relational environment

Beneath the visible machinery of politics lies the quiet architecture of everyday life. Polarization endures through the social ecologies we inhabit—the neighborhoods we choose, the circles we frequent, the people we no longer meet. Sociologists call this pattern homophily: the human tendency to associate with those who resemble us. What was once a subtle inclination has hardened into the default geometry of American life. We live, study, marry, and worship within ideological enclaves. The country’s physical and moral landscapes have come to mirror each other.

In The Big Sort (2008), Bill Bishop documented how counties across the United States grew increasingly homogeneous, as Americans self-segregated by lifestyle and politics alike. The pattern has only intensified. Dating apps now filter users by ideology as casually as by age or distance; a recent Pew survey found that nearly two-thirds of both Republicans and Democrats say they would prefer not to date someone from the other party. Even churches and civic associations, once among the few remaining spaces of political mixture, have fractured along red and blue lines. The loss is not merely statistical. In dissolving the everyday friction of difference—the neighbor who votes differently, the colleague who sees another side—we lose the apprenticeship of pluralism itself. The habits that sustain democracy are learned in proximity.

The result is a society dense with networks but thin in connection—a web of like-minded islands, each convinced it represents the mainland.

The sociologist Robert Putnam once described social capital as the “glue” that holds communities together. Polarization erodes that glue from both ends: it weakens trust across lines of belief and strengthens it only within them. The result is a society dense with networks but thin in connection—a web of like-minded islands, each convinced it represents the mainland.

6. Epistemic Infrastructure — the truth architecture

When trust collapses, knowledge itself fractures. The institutions once regarded as referees of truth—journalism, science, the academy—no longer command universal legitimacy. Their authority has become conditional, filtered through the same partisan lens that distorts politics. Citizens no longer ask “Is it true?” but “Whose truth is it?” Verification now depends on the perceived virtue of the speaker.

The epistemic infrastructure of democracy—the web of trust, method, and institutional credibility through which societies discern reality—is its nervous system. When its signals fail, the civic body loses coordination. Competing media ecosystems, partisan think tanks, and ideologically curated feeds transmit contradictory impulses, leading to parallel worlds with distinct facts, experts, and logics. The American public sphere today resembles a schism of realities. Conservative and progressive media sustain separate epistemologies, each with its own canon of trustworthy outlets and heretical others. Fact-checking organizations, once intended as neutral arbiters, now fact-check one another, reflecting the recursive mistrust of the age. Even on empirically measurable issues—election integrity, climate change, or public health—disagreement often concerns not the data but the legitimacy of those interpreting it.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt warned that the deliberate blurring of fact and opinion was the prelude to totalitarianism, for it rendered citizens incapable of distinguishing between persuasion and reality (Truth and Politics, 1967). Today’s fragmentation appears more a byproduct of a marketplace that rewards engagement over accuracy. Yet the effect is the same: a society unsure not only of what is true, but of whether truth itself still matters.

To rebuild an epistemic infrastructure is to recover the moral discipline of shared reality: the humility to know that truth is not possession but pursuit. Without that, civic discourse becomes a hall of mirrors—each reflection sharper, louder, and less human than the last.

To rebuild an epistemic infrastructure is to recover the moral discipline of shared reality: the humility to know that truth is not possession but pursuit. Without that, civic discourse becomes a hall of mirrors—each reflection sharper, louder, and less human than the last.

7. Moral-Spiritual Infrastructure — the foundation of meaning

Beneath every institution and algorithm lies a deeper stratum—the moral soil in which civic life either roots or rots. Political systems are sustained by a tacit moral imagination: including the belief that fellow citizens are owed good faith, even when they are wrong. When that imagination collapses, democracy may persist in form, but its spirit withers and fraternity dies. This is the infrastructure of virtue, the layer that no policy can legislate but upon which all others depend. Here dwell the habits that make freedom habitable: humility, mercy, patience, and forgiveness. They are the quiet technologies of civic life, the unwritten code that keeps conflict from turning into enmity.

The signs of erosion are everywhere. Forgiveness, once regarded as a civic as well as a religious virtue, has withered in public culture. Social media’s permanent memory ensures that moral failure has no statute of limitations. Every misstep becomes a digital fossil, unerasable and unredeemable. In this moral economy, penance is impossible, punishment perpetual. The culture of cancellation—whether from left or right—replaces moral repair with exile, turning repentance into a performance and mercy into weakness.

The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre once wrote that a society without shared virtue lacks the moral resources to sustain its own arguments (After Virtue, 1981). That is the stage we approach: a civic realm fluent in accusation but mute in absolution. The loss is ontological; when we cease to believe in redemption, we cease to believe in persons.

That is the stage we approach: a civic realm fluent in accusation but mute in absolution. The loss is ontological; when we cease to believe in redemption, we cease to believe in persons.

Democracy cannot survive on rules alone. It requires citizens capable of grace—of seeing in their adversary not an enemy of truth, but a bearer of it in another form. Only in that recognition can pluralism become more than tolerance - communion amid discord.

Together, these seven layers form the living anatomy of polarization — a system that converts psychological bias into digital behavior, digital behavior into institutional incentive, and institutional incentive into moral exhaustion.

Repairing democracy, therefore, cannot mean adjusting only the surface machinery. It must involve rebuilding the deep infrastructures — cognitive, emotional, social, epistemic, and spiritual — that once made pluralism not merely bearable, but fruitful.

The genius — and danger — of polarization as infrastructure is that it learns. It absorbs critique and converts it into content. Civic education campaigns, algorithm audits, and “bridge initiatives” often fail because they are metabolized by the system: they become new occasions for identity signaling.

Polarization evolves through various feedback loops that self-correct dysfunction without ending it, such as:

- Saturation: Outrage cannot keep growing indefinitely; it reaches profitable equilibrium.

- Sorting: Citizens adjust party identities to match social and moral identities, rather than the reverse.

- Elite Cues: Political elites weaponize division to mobilize donors and followers; the mass public follows emotional cues, not policy.

- Normalization: Constant exposure to hyperbole dulls moral alarm. Conflict becomes civic wallpaper.

This adaptive equilibrium explains why polarization seems immune to reform. It is not an aberration but a systemic success. The machinery works — just for the wrong ends.

This adaptive equilibrium explains why polarization seems immune to reform. It is not an aberration but a systemic success. The machinery works — just for the wrong ends.

The most common response to polarization is technocratic: fix the algorithm, redraw districts, regulate misinformation. These measures are necessary but insufficient. They touch only the surface mechanics of a deeper moral crisis.

As Iris Murdoch wrote, “The self, the place where we live, is a place of illusion” (The Sovereignty of Good, 1970). That illusion—the conviction that our own view is pure, our tribe uniquely virtuous—is the oldest temptation of the human heart. Catholic thought names it pride, the curving of the soul inward upon itself (curvatus in se - Augustine). Against that inward turn, both Murdoch and the Christian tradition propose the same remedy: attention, a disciplined act of love that looks outward, truthfully and humbly, toward what is real. For Aquinas, charity (caritas) is right seeing—the grace that orders perception. To love rightly is to see rightly. Polarization thrives where this vision fails, when politics becomes a theater of moral self-affirmation rather than a practice of mutual regard. Renewal, then, begins not in new systems but in conversion of vision: the unselfing of the gaze that allows truth to appear again as something shared, not possessed.

Polarization thrives where this vision fails, when politics becomes a theater of moral self-affirmation rather than a practice of mutual regard. Renewal, then, begins not in new systems but in conversion of vision: the unselfing of the gaze that allows truth to appear again as something shared, not possessed.

So while every effort to combat polarization is commendable, at Concordia Discors Magazine we argue that policy must pair with virtue formation: civic education that cultivates habits of humility, patience, and responsibility.

So while every effort to combat polarization is commendable, at Concordia Discors Magazine we argue that policy must pair with virtue formation: civic education that cultivates habits of humility, patience, and responsibility.

We cannot stress enough that virtue is not sentimentalism. It is the invisible architecture of freedom — the set of moral disciplines that make pluralism and democracies sustainable and human beings flourish.

Five virtues, in particular, function as counter-infrastructures:

| Pathology | Counter-Virtue | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive bias | Humility | Admits fallibility, reopens curiosity. |

| Emotional outrage | Temperance | Moderates reaction, restores judgment. |

| Tribal conformity | Courage | Enables dissent within one’s side. |

| Social segregation | Charity | Humanizes the adversary. |

| Truth fragmentation | Responsibility | Grounds belief in reality, not tribe. |

Without such virtues, even the best policy instruments degrade into new battlefields.

If polarization is infrastructural, then depolarization must be architectural. The task is not to abolish conflict — pluralism requires it — but to civilize it.

If polarization is infrastructural, then depolarization must be architectural.

Policy must therefore focus on reconstructing three interdependent layers of civic life:

- Cognitive Renewal: Schools and public institutions should teach attentional discipline — the ability to pause before reacting, to weigh competing truths.

- Institutional Repair: Political and media institutions must build incentives for cooperation across difference, especially at the local level. Rewarding dissent within one’s side — rather than punishing it — is the mark of institutional maturity.

- Epistemic Restoration: Journalists and scholars should model intellectual humility by disclosing uncertainty and limits. Public trust grows when experts admit what they do not know.

As Max Weber reminded us in Politics as a Vocation (1919), “Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards.” And reforming democracy’s infrastructure is precisely that kind of labor — patient, disciplined, often thankless, but indispensable.

The goal of a healthy democracy is not consensus but coexistence. The infrastructure of polarization degrades that harmony without apparent benefits. But if it has been built, it can be rebuilt. Doing so requires courage, imagination, and the humility to see disagreement not as a flaw but as the condition of freedom itself.

We are, in the end, engineers of the soul as much as of the system. The reconstruction of pluralism will begin not with a new algorithm, but with a new attention — the courage to look again at those we have learned to despise, and to see in them, once more, a fellow citizen, with flaws and virtues. ◳

The reconstruction of pluralism will begin not with a new algorithm, but with a new attention — the courage to look again at those we have learned to despise, and to see in them, once more, a fellow citizen, with flaws and virtues.