Epstein and the Most Polarizing Idea in the World. That Every Life has Equal Value.

Epstein’s contempt for equal human worth was not incidental. The claim that every person bears inviolable dignity is a metaphysical limit, one that makes trafficking, eugenics, and exemption morally unintelligible.

Among the millions of pages the U.S. Department of Justice released on January 30, 2026, under the Epstein Files Transparency Act, two exchanges illuminate something even larger than the depraved crimes and moral barathrum of his gang. They frame a theory of human (un)worth.

In a 2013 email, Jeffrey Epstein derides the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for what he calls the “ludicrous statement that every life is equal,” adding: “It is Catholicism at its worst.” Elsewhere in the same tranche, the Hollywood producer Barry Josephson writes to Epstein about a question he says was put to Bill Gates: “How do we get rid of poor people as a whole?” Josephson claims to have “an answer” and asks to schedule a call. The provenance and context are unclear, and Gates has not publicly addressed the remark. But the register is the point. In this milieu, the disposability of entire categories of human beings can be floated as a dinner-party proposition, spoken with the managerial calm of a portfolio rebalance.

Epstein was not a theologian; he was a sex trafficker. By the evidence now laid bare, he was a man who sorted human beings into the useful and the expendable.

Epstein was not a theologian; he was a sex trafficker. By the evidence now laid bare, he was a man who sorted human beings into the useful and the expendable. Yet the quasi-theological contempt for equal human worth that animates his crimes throws into relief a Catholic doctrine our civilization cannot survive without.

These details form a single, coherent pattern. Epstein’s plan to “seed the human race with his DNA,” modeled on eugenics-era sperm banks, and his fixation on blue eyes as markers of intelligence reflect a view of humanity ordered by genetic hierarchy. His dismissal of Christian repentance as “forced speech” follows the same logic: a rejection of any moral framework in which all persons stand equally accountable. What looks like eccentricity and depravity, is in fact an anthropology, one that denies equal human worth and reserves exemption for the strong. Any attempt to recognize equal value of human beings would have rendered his entire existence, from the trafficking to the transhumanism, "morally" unintelligible.

The pattern is coherent. Epstein rejected any framework in which all persons possess equal inherent worth, because such a framework would have rendered his entire existence, from the trafficking to the transhumanism, morally unintelligible.

But his contempt for the Gates Foundation’s guiding principle was more theologically precise than he intended. That principle, stated on the foundation’s website, reads: “Guided by the belief that every life has equal value.” This is indeed an inheritance from Catholic social teaching, rooted in a doctrine older than Christendom: the belief that every person, without exception, is made in the image of God. And it is, as Epstein intuited, one of the most polarizing and consequential ideas ever advanced.

The claim requires explanation, because it is both more radical and more specific than it sounds. The Hebrew phrase is b’tzelem Elohim, “in the image of God.” It appears in the first chapter of Genesis: “And God created humankind in the divine image.” It wasn't the poetry to make this revolutionary, but its politics. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, “image of God” was a royal title for pharaohs and kings. Torah democratized it. Every person, from monarch to slave, carries the same likeness. Larry Siedentop, in his Inventing the Individual, argued that this was the hinge of Western civilization: the ancient world assumed natural inequality as cosmic fact; the Judeo-Christian tradition overturned it (Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism, 2014). From that overturning, Siedentop traced the slow emergence of individual rights, conscience, and the pluralist order we now take for granted. The claim is contested, but its core insight stands: the idea of the equal individual is not a self-evident truth that reason discovers unaided. It is a historical achievement, and its deepest taproot is theological.

The claim is contested, but its core insight stands: the idea of the equal individual is not a self-evident truth that reason discovers unaided. It is a historical achievement, and its deepest taproot is theological.

The political consequences of this claim are immense and largely invisible, in the way that foundations are invisible to those who live in the house above. Jacques Maritain, decisive in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, grounded the entire edifice in imago Dei: "A person possesses absolute dignity because he is in direct relationship with the absolute" (The Rights of Man and Natural Law, 1944). When delegates from radically different civilizations could agree on a list of rights but not on their philosophical justification, Maritain offered his famous remark: "Yes, we agree about the rights, but on condition that no one asks us why." The observation is usually treated as a charming concession to pluralism, proof that human rights need no metaphysical foundation. It is better understood as a warning. A house that refuses to inspect its foundation is simply unaware of the moment when the cracks become structural. We have spent eighty years building an international order on the principle that every person possesses inherent dignity, while systematically dismantling the intellectual tradition that explains why this should be so.

We have spent eighty years building an international order on the principle that every person possesses inherent dignity, while systematically dismantling the intellectual tradition that explains why this should be so.

The result is edging closer to a civilization living off moral capital it no longer knows how to replenish. Hannah Arendt understood what happens when an inheritance is retained in language but abandoned in substance. Surveying the wreckage of stateless peoples amid world wars, she concluded that rights proclaimed without a sustaining principle of belonging dissolve into impotence. Abstract dignity, detached from any (state) authority capable of guaranteeing it, becomes a slogan. “Human dignity,” she warned, “needs a new guarantee… a new law on earth” whose validity would comprehend all humanity (The Origins of Totalitarianism, 1951). Arendt did not pretend to have found that guarantee. She named the abyss that opens when none exists.

This is where Epstein’s sneer reveals its deeper error. He grasped that the claim “every life has equal value” is a metaphysical obstacle, a hard limit on what the strong may do to the weak. What he mistook was the lesson of its fragility. The fact that Arendt could not replace the theological foundation does not license its abandonment; it exposes the cost of living without it. When equal dignity is treated as optional, human beings revert to what Epstein practiced instinctively: sorting, breeding, discarding. Epstein showed us who benefits when it does.

When equal dignity is treated as optional, human beings revert to what Epstein practiced instinctively: sorting, breeding, discarding. Epstein showed us who benefits when it does.

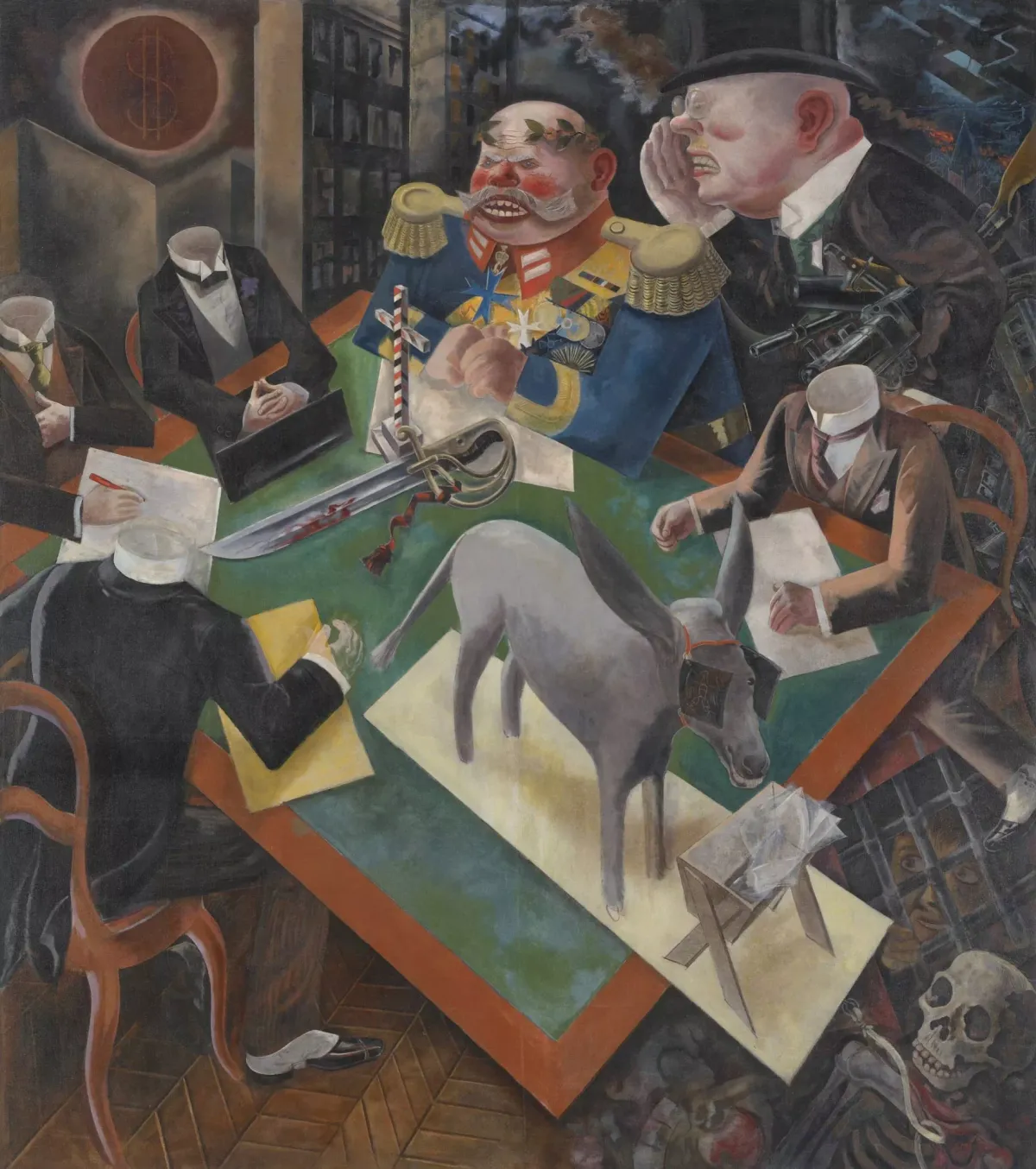

The whole point of imago Dei is that dignity does not depend on recognition. It precedes it. Remove that precedence, and rights become a conditional grant, bestowed by the powerful, revocable at will. That revocation is a constant force of history from opposing directions, each convinced it speaks in the name of freedom. On one side, a humanitarian utilitarianism quietly replaces inherent worth with functional capacity, expanding regimes of assisted death beyond the terminally ill to the merely burdensome. On the other, a post-Christian vitalism replaces dignity with strength, treating hierarchy as honesty and cruelty as clarity. The movements share no culture and no coordination, but they share an anthropology: that human worth is contingent, on capacity, productivity, or power, and that the language of equal dignity is a residue of a religious past we have outgrown.

Simone Weil could help us with a passage of beauty and hope. She locates the ground of human dignity not in autonomy, personality, or rational capacity, but in a more elemental and universal experience: affliction and rootlessness. What unites humanity, she argues, is not shared achievement or consent, but a common vulnerability before the good. “At the bottom of the heart of every human being, from earliest infancy until the tomb,” she writes, “there is something that goes on indomitably expecting that good and not evil will be done to him” (Human Personality, 1943). This “childlike” expectation is not learned, argued into existence, or culturally contingent; it precedes reflection and survives degradation. Unlike Augustine’s memoria Dei, which recalls God through the intellect, Weil points to an expectant orientation of the heart. The good is not remembered but awaited. In this sense, the good, whether named explicitly as God or not, appears as a universal presence, lodged in every human being and expressed in diverse, historically contingent forms. It is this shared expectation, rather than any shared doctrine, that marks the irreducible sacredness of the human person.

In this sense, the good, whether named explicitly as God or not, appears as a universal presence, lodged in every human being and expressed in diverse, historically contingent forms. It is this shared expectation, rather than any shared doctrine, that marks the irreducible sacredness of the human person.

This is what imago Dei names in secular language: that there exists in every person something not produced by circumstance, not conferred by society, and not within the jurisdiction of the powerful. Epstein’s life was an attempt to prove otherwise. The files now released are the record of that attempt, and, inadvertently, of its failure and descent into a moral barathrum

Epstein was right that the belief in equal human worth is Catholic in origin and character. He was right that it obstructs every system that sorts persons by utility, power, or genetic promise. He called it "Catholicism at its worst".

What his sneer missed is the more dangerous truth: the doctrine is not ornamental. It is load-bearing. Remove it, and the structure it supports collapses into something very old: a world organized around the self-evident supremacy of the strong, where the question “How do we get rid of poor people as a whole?” is not monstrous but merely practical. The Epstein files are not, in the end, just a story about depravity of a gang of beings. They are a glimpse of the reality that emerges when the premise of human dignity Epstein mocked is discarded. ◳

The Epstein files are not, in the end, just a story about depravity of a gang of beings. They are a glimpse of the reality that emerges when the premise of human dignity Epstein mocked is discarded.