David Boaz’s Case for a Confident, Cosmopolitan Freedom

Boaz reminds us liberty is not a bunker but a port city—confident, cosmopolitan, and outward-facing. Peace, trade, and humility in power are its pillars; connection, not coercion, is its compass.

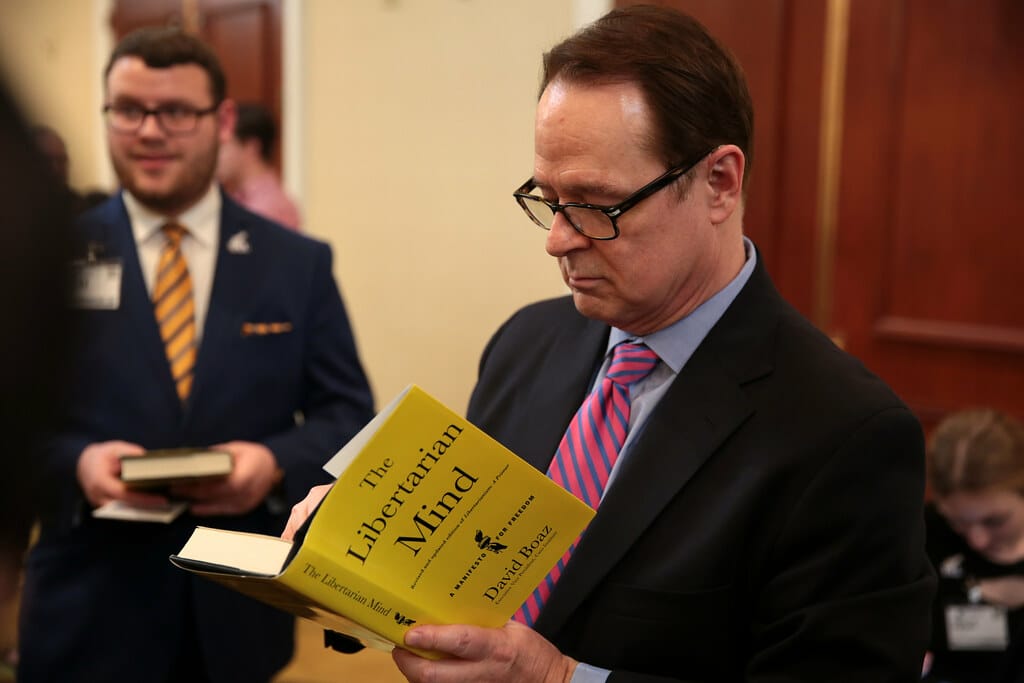

I was turning the pages of David Boaz’s The Libertarian Mind when a sentence caught like flint:

“Libertarians are in fact confident and cosmopolitan… we look forward to a world bound together by free trade, global communications, and cultural exchange.”

Boaz’s phrasing is memorable because it restores something essential to the liberal tradition: an outward-facing confidence that prefers connection to command, persuasion to force, and trade to tribute.

This is the sober inheritance of classical liberalism. Adam Smith’s spare triad—“peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice”—remains a political north star. George Washington advised that America should extend “commercial relations” while keeping “as little political connection as possible.” Jefferson’s first inaugural reduced it to a maxim: “peace, commerce, and honest friendship… entangling alliances with none.” Boaz channels this lineage for the present: war is exceptional; peace is the default that lets ordinary life flourish.

Boaz’s chapter on preserving peace is a gem - sets out a few unflinching truths:

- War destroys liberty. Emergencies centralize power, inflate budgets, and normalize surveillance; those “temporary” measures rarely vanish on schedule. From World War price controls to modern executive overreach, the pattern is constant.

- War kills indiscriminately. In the modern era, civilians die alongside soldiers. Hence proposals to dispatch troops abroad should be met—Boaz argues—with disciplined skepticism, and justified only by defense against clear aggression and limited ends.

- Empire is a mirage. No state can “police and plan the whole world” any more than it can plan a national economy. The unintended consequences of open-ended missions are routinely larger than the aims that launched them.

- Allies aren’t dependents. Europe and South Korea can defend themselves; a permanent American security subsidy corrodes responsibility abroad and liberty at home.

- Citizens aren’t in the dark. The communications revolution narrows the gap between leaders and the public. When presidents are watching crises on the same satellite channels as everyone else, consent matters—and should restrain adventurism.

Boaz draws a straight line to first principles: the primary purpose of government is to protect the rights of citizens. That requires a formidable defense, but not a globe-spanning project of social engineering. Call this a foreign policy of defense and restraint—strong enough to deter, modest enough to avoid the conceit of managing other peoples’ destinies.

Boaz’s cosmopolitanism isn’t a plea for a supranational leviathan. It is a civic posture.

Boaz’s cosmopolitanism isn’t a plea for a supranational leviathan. It is a civic posture: confidence that free people, across borders, can cooperate without a single manager. It delights in exchange—of goods, code, music, and ideas. It trusts that repeated contact civilizes our habits (Montesquieu’s doux commerce) and raises the cost of conflict.

Here the affinities with kindred thinkers are clear. Isaiah Berlin’s pluralism counseled against “final harmonies”; Karl Popper urged piecemeal change in an open society. Boaz gives those insights policy teeth: if values are many and knowledge is dispersed, humility—about what force can accomplish—becomes a virtue of statecraft, not an evasion of duty.

Because Boaz insists on limits, critics sometimes affix the old label “isolationist.” It misses the point. His argument is for maximum engagement by private people—trade, travel, study, migration—paired with maximum caution by governments when they contemplate war. The world gets more cosmopolitan when societies open ports and minds; it doesn’t when great powers try to adjudicate every quarrel.

That is why Boaz defends maintaining the world’s most capable defensive force while opposing the reflex to escalate regional wars into superpower contests. In a nuclear age, prudence is not timidity; it is moral realism.

Libertarians rightly recoil from “world government,” but that does not imply indifference to global forums. A cosmopolitan liberalism can value institutions that lower the costs of peaceful cooperation—so long as they are limited, transparent, and accountable to citizens. In that spirit:

- Prevent and end wars. Focus multilateral energy on mediation, cease-fire monitoring, and narrowly mandated peacekeeping with clear exits. Conflict de-escalation is a public good; social engineering is not.

- Protect refugees and enable relief. Coordinate safe corridors and logistics so private and civic actors can move faster. Subsidize speed, not bureaucracy.

- Defend core liberties as common language. The Universal Declaration’s basics—speech, conscience, association, due process—remain the best foundation for coexistence among different civilizations.

- Publish what you learn. Open data on atrocities, displacement, and disease; let journalists, researchers, and innovators use it to hold the powerful to account and to solve problems.

- Respect subsidiarity. Push decisions down to the most local level capable of handling them; prefer networks to hierarchies.

That is not a blueprint for utopia; it is a modest checklist for institutions that want the trust of free people.

Boaz understood that the case for peace is also a case about character. War flatters our appetite for unity and our hunger for enemies who make identity easy. Cosmopolitan liberalism demands a different courage: the patience to negotiate, to trade, to argue in public rather than punish in private, and to forgo the intoxicating drama of “saving the world” in favor of building one in which fewer require saving.

Cosmopolitan liberalism demands a different courage: the patience to negotiate, to trade, to argue in public rather than punish in private, and to forgo the intoxicating drama of “saving the world” in favor of building one in which fewer require saving.

Alasdair MacIntyre’s famous line helps here: “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’” The libertarian answer is plural: we inhabit many stories, and politics should leave ample space for them to unfold without coercion. That, too, is cosmopolitan confidence.

David Boaz spent a lifetime defending liberty with clarity and grace. He argued for policies—but he also modeled a temperament: outward-looking, intellectually generous, and allergic to inflated power. In an era of anxious nationalism and permanent emergencies, his counsel is steadying:

- Prefer connection to coercion—trade agreements over tariffs, student visas over purity tests, open communications over information controls.

- Keep armed force decisive but sparing—reserved for defense, bounded in aim, and honest about costs.

- Judge institutions—national and international—by a simple test: do they enlarge the space in which free people can live together in difference?

Boaz reminded us that liberty is not a bunker; it is a port city. Confident and cosmopolitan, it faces the world without fear—and builds a peace worth keeping.

Boaz reminded us that liberty is not a bunker; it is a port city. Confident and cosmopolitan, it faces the world without fear—and builds a peace worth keeping.