Dancing while Smolensk Fall. Preference Falsification and the Hidden Fragility of Political Order

From Tacitus’s obsequium to Miłosz’s Persian-borrowed ketman and Havel’s greengrocer, political orders endure less by force than by disciplined inattention. Preference falsification explains how societies sustain consensus no one truly believes.

In the forty-second chapter of his Agricola, Tacitus delivers a judgment that has troubled consciences for two millennia. Writing of his father-in-law's conduct under the tyranny of Domitian, he observes that great men can exist even under bad emperors, and that obsequium ac modestia, compliance and moderation, if joined to industry and vigor, may achieve a glory equal to that won by those who court spectacular ruin through useless defiance. Most modern historians read this as Tacitus’s attempt to justify a via media between heroic defiance and total capitulation. The passage reads as apology, vindication, and warning simultaneously. Agricola survived; the martyrs did not; and Rome endured. But what was the cost of such survival to the soul?

This question did not die with Rome. It echoes through the Persian practice of ketman, through the elaborate camouflage of Renaissance Nicodemites, through the frozen silences of Stalinist committee rooms, and into the algorithmic conformities of our own digital commons. In 1995, the economist Timur Kuran gave this phenomenon a name that cut through centuries of euphemism: preference falsification. The act of misrepresenting one's wants under perceived social pressure is, Kuran argued, not merely ubiquitous but constitutive of political order itself (Kuran, Private Truths, Public Lies, 1995). Regimes do not stand only on bayonets, they stand on the accumulated weight of a million small lies.

The act of misrepresenting one's wants under perceived social pressure is, Kuran argued, not merely ubiquitous but constitutive of political order itself.

Yet before we accept Tacitus's pragmatism too readily, we must ask a harder question: Is there a principled distinction between prudential accommodation and moral capitulation? Thomas Aquinas, following Aristotle, distinguished between acts that are intrinsically evil and acts whose moral character depends on intention, object, and circumstance (Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 18). A man may pay taxes to a tyrant without sin; he may not denounce the innocent to save himself. This framework suggests that the Tacitean calculus is not inherently corrupt, but it carries spiritual dangers that Tacitus himself half-perceived. Augustine warned that the habits of the will shape the soul: "Habit, if not resisted, soon becomes necessity" (Confessions, VIII.5). What begins as strategic compliance can become, through repetition, a second nature indistinguishable from genuine conviction.

Czesław Miłosz encountered this paradox in its twentieth-century form. In The Captive Mind (1953), he introduced Western readers to the concept of ketman, borrowing a Persian term for the concealment of heterodox beliefs under persecution. The intellectuals of Soviet-dominated Poland had developed elaborate strategies of internal resistance that allowed them to maintain a sense of moral superiority while performing, flawlessly, the rituals of ideological conformity. The psychological appeal was seductive: a "peculiar masochistic delight" in outwitting the regime, in knowing that somewhere behind the mask an authentic self remains intact. But Miłosz was clear-eyed about the dangers. The mask, worn too long, begins to fuse with the face. "A man grows into it so closely that he can no longer differentiate his true self from the self he simulates." (Chapter III - The Captive Mind)

This decay points to a deeper problem: belief is not a possession that can be stored indefinitely in the private recesses of the mind. It requires exercise, articulation, and communal reinforcement to remain alive. John Henry Newman understood this when he argued that faith is sustained not by private conviction alone but by the "illative sense" - the accumulated habits of judgment formed through practice and community (An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, 1870). A belief that is never spoken, never tested in dialogue, never embodied in action, does not simply remain dormant. It withers.

John Henry Newman understood this when he argued that faith is sustained not by private conviction alone but by the "illative sense" - the accumulated habits of judgment formed through practice and community.

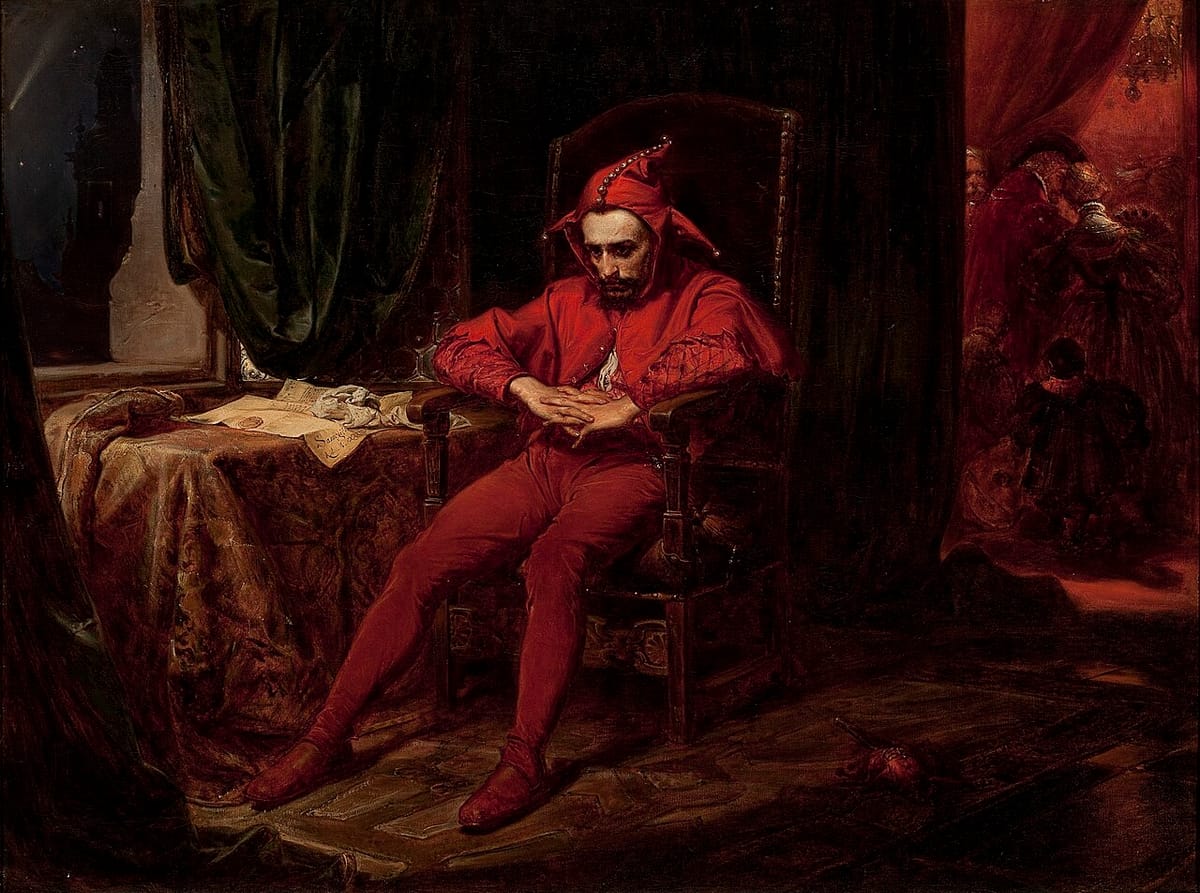

Václav Havel gave this insight its most politically potent formulation. In "The Power of the Powerless" (1978), he offered the parable of the greengrocer who places in his shop window the sign: "Workers of the world, unite!" The greengrocer does not believe in the unity of workers. He displays the sign because compliance purchases peace. But its true message is: "I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace." The sign is a signal of submission disguised as conviction, and its disguise is essential. If instructed to display "I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient," he would be ashamed. The ideological formulation allows him to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience.

The greengrocer does not believe in the unity of workers. He displays the sign because compliance purchases peace.

Havel recognized that this mechanism created a "world of appearances" that everyone sustains and no one believes. Each dissenter believes himself unique, surrounded by true believers, when in fact nearly everyone is dissenting in private and conforming in public. This is pluralistic ignorance at civilizational scale.

This is pluralistic ignorance at civilizational scale.

Kuran's theoretical apparatus explains how such systems persist and why they collapse so suddenly. Preference falsification involves a trade-off among three utilities: the reputational utility of conforming; the expressive utility of honesty; and the intrinsic utility of preferred outcomes. Because preference falsification hides the distribution of true beliefs, the tipping point cannot be observed in advance. A single triggering event can suddenly lower the perceived cost of honesty. When a few people stop displaying the sign, others who were waiting see that defection is possible, and the cascade accelerates. Regimes that seemed eternal dissolve in weeks. This is why 1989 surprised nearly everyone, including the dissidents themselves.

But the analysis so far has focused on elites: intellectuals, writers, dissidents. What of the ordinary believer who lacks the vocabulary of ketman but faces the same pressures? The historical record suggests that non-intellectual resistance was often rooted in religious practice. In Poland, pilgrimages to Jasna Góra were acts of collective witness requiring no intellectual sophistication, only the willingness to walk. The underground Church in Czechoslovakia, samizdat prayer circles in the Soviet Union, house churches in contemporary China. These preserve belief not through argument but through shared ritual. The man who prays alone may lose heart; the community that prays together sustains its members through the darkest seasons. The architecture of dissimulation is powerful, but it cannot easily penetrate communities bound by practices with their own logic and rewards.

The man who prays alone may lose heart; the community that prays together sustains its members through the darkest seasons.

This suggests a crucial distinction. The mechanisms of preference falsification may be structurally similar across totalitarian regimes and liberal democracies, but the moral contexts are profoundly different. When Havel's greengrocer removes his sign, he faces imprisonment or death. When a contemporary academic declines to sign a statement, he faces professional inconvenience. To conflate these situations dishonors those who resisted genuine tyranny. Yet the difference is one of degree, not kind. The dynamics of spiral silence operate wherever conformity carries reward and deviation carries punishment. In corporate offices where employees nod along to presentations they privately mock, in faculty meetings where scholars remain silent about scholarship they consider fraudulent, in social media spaces where the cost of heterodoxy is measured in lost connections and damaged reputations. Systems that begin with mild pressures toward conformity can, if unchecked, escalate into something far more coercive. The boundaries of acceptable discourse, once they begin to contract, do not contract by themselves.

Freedom of speech lowers the penalty for dissent.

What distinguishes liberal democracy, at its best, is not the absence of preference falsification but the presence of institutional mechanisms designed to interrupt its dynamics. Secret ballots allow preferences to be expressed without reputational cost. Freedom of speech lowers the penalty for dissent. Competitive elections create incentives for politicians to represent latent preferences. These are hard-won achievements requiring continuous maintenance. When they erode, when speech becomes costly, when institutions demand public affirmation of positions that cannot be questioned, the pathologies return, now disguised in the language of freedom.

Yet even Havel recognized that individual refusals, however morally necessary, are not sufficient for institutional repair. What is needed are institutions that make honesty less costly and conformity less automatic, that create the conditions for concordia discors: harmony through the management of discord, stability through the legitimate expression of disagreement.

The Catholic tradition offers resources for this that secular theory has not sufficiently appreciated. The doctrine of subsidiarity recognizes that truth is discovered through multiple, overlapping communities of inquiry. When intermediate institutions are absorbed by state or market, the ecology of truth-seeking collapses. Similarly, the Thomistic account of conscience provides a framework for legitimate dissent. Conscience can err, but the individual is bound to follow it even when it errs, because to act against conscience is always sinful (Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 19, a. 5-6). A society that takes conscience seriously will create mechanisms for dissent that neither punish it automatically nor privilege it absolutely.

A society that takes conscience seriously will create mechanisms for dissent that neither punish it automatically nor privilege it absolutely.

The task is difficult because preference falsification is self-reinforcing. Each act of strategic conformity raises the perceived consensus and therefore the cost of future dissent. Breaking this cycle requires what Kuran calls "preference pioneers", individuals whose willingness to express unpopular views lowers the cost for others. But preference pioneers pay a price, and there is no guarantee their sacrifice will succeed.

What sustains the preference pioneer? Here religious traditions offer something secular accounts cannot match. The martyr's witness is intelligible only within a framework that values fidelity to truth more than survival. Augustine's City of God explained how the sack of Rome could be borne: the earthly city is not the final reality. The greengrocer who refuses the sign because he fears God more than the Party has a resource the secular dissident lacks: a reason to persist even when persistence appears futile.

The greengrocer's sign is still in the window. The task of political and institutional design is to create conditions under which it can be taken down, not because the authorities have fallen, but because they have recognized that legitimacy depends on something other than accumulated lies. This requires not only institutional reform but cultural renewal: the recovery of practices that form conscience, communities that sustain belief, and virtues that make honesty possible even when costly.

Such renewal cannot be manufactured by policy. It emerges from the slow work of formation, in families, parishes, schools, and associations where the habits of truth-telling are cultivated before they are tested.

Such renewal cannot be manufactured by policy. It emerges from the slow work of formation, in families, parishes, schools, and associations where the habits of truth-telling are cultivated before they are tested. Newman called this the "discipline of mind" that enables the individual to hold firm when the world demands capitulation. Aquinas called it fortitude. Whatever we call it, it is not produced by institutional incentives alone. The institution can make honesty less costly, but it cannot make honesty attractive to those who have never learned to value it.

The institution can make honesty less costly, but it cannot make honesty attractive to those who have never learned to value it.

The lesson of Tacitus, Miłosz, Havel, and Kuran is not that dissimulation is always wrong, there are tyrants before whom only the reckless speak freely, but that it carries a cost that must be counted. The soul that accommodates too often may forget how to resist. And the society that loses the capacity to distinguish strategic compliance from genuine conviction may find itself unable to recognize truth even when it is spoken. The remedy is not heroic individualism, which asks too much and offers too little. It is the patient construction of communities and institutions that make conscience sustainable: that provide the formation, the fellowship, and the framework within which private conviction can find public expression without requiring martyrdom as the price of honesty.

This is the work of generations, but it is work that can begin wherever a few people choose to stop performing and start speaking, not because victory is assured, but because some things are worth saying whether or not the world is ready to hear them. Until that renewal occurs, the architecture of dissimulation will continue to do its quiet work, building structures that appear solid and proving, in the end, to have been built on air. ◳