Dag Hammarskjöld and the Inner Life of Service

Hammarskjöld’s Markings shows that true leadership is rooted in humility, integrity, and service. His legacy reminds us that moral authority flows not from power, but from the courage to surrender self for others.

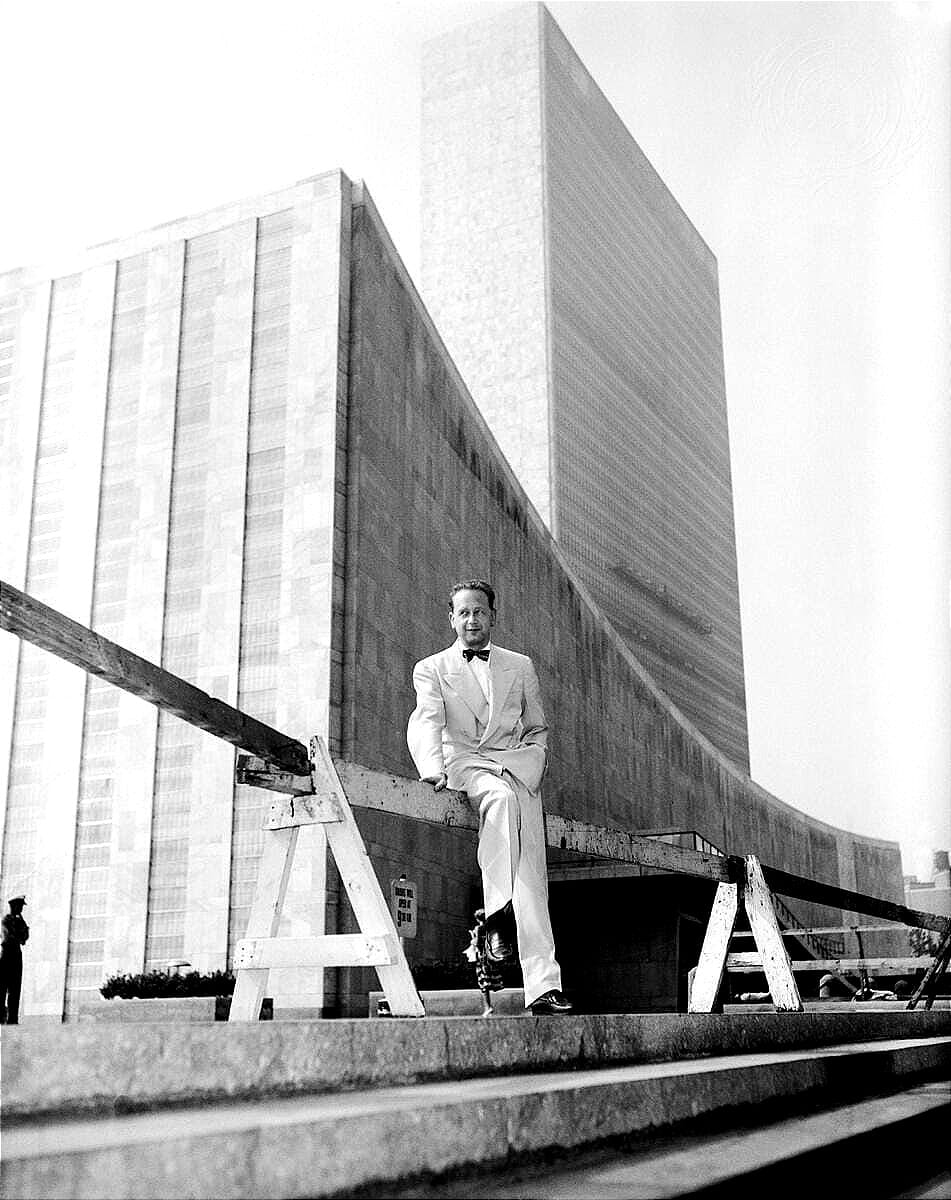

When Dag Hammarskjöld’s plane crashed in 1961 over the forests near Ndola, Zambia en route to peace talks, the world lost a singular leader. As the United Nations’ second Secretary-General (1953–1961), this Swedish economist carved a bold path, elevating the UN above the chessboard of international politics. Yet it was his private journal, Markings—a collection of fragments, prayers, reflections on failure, and poems of surrender gathered over his life—that revealed the soul behind the statesman. In a letter, he called it “a sort of white book concerning my negotiations with myself—and with God.”

Markings is “a sort of white book concerning my negotiations with myself—and with God.”

Far from a diary of events, it was a raw ledger of his inner struggles, a testament to a man who saw leadership not as conquest but as consecration. For today’s leaders, Hammarskjöld’s life—equal parts mystic and hard-nosed diplomat—offers a profound lesson: true authority flows from humility, integrity, and an unflinching commitment to service, even when the world demands moral concessions.

Markings is Dag Hammarskjöld’s candid self-portrait, a record of unyielding introspection. He rejected hollow triumphs, noting, “If your goal is not hallowed by your most inner passion, even a victory will make you painfully aware of your own weakness.” True success, for him, lay in unwavering commitment to purpose: “Your only possible achievement—not to have deserted.” To stray from one’s calling for convenience was to betray the essence of public service.

“If your goal is not hallowed by your most inner passion, even a victory will make you painfully aware of your own weakness.”

Humility defined him. He admired those who faced defeat without self-pity and success without vanity. Guided by the principle “Not I, but God in me,” inspired by Christian mystics, he saw leadership as selfless service. Hammarskjöld sought no personal glory; he devoted himself to a higher purpose.

Hammarskjöld viewed life not as a possession to be guarded, but as a trust to be handed on. Even death, he wrote, should be purposeful: “Death must be your final gift to life, not an act of treachery against it”. “Birth and death, surrender and pain—the reality behind the dance under the floodlights of social responsibility” captures his belief that public life was a performance masking deeper sacrifice. In the early 1950s, he answered his calling with a resolute “Yes”, and soon after became Secretary-General—a role he saw as an altar, not a throne. “The gift is God’s—to God”, he wrote, casting his work as a spiritual mission, not a platform for power.

“The gift is God’s—to God”

Unlike later UN leaders judged by political maneuvering, Hammarskjöld saw his role as self-offering. His quiet diplomacy bore fruit: in 1955, he negotiated the release of American airmen held by China, deftly navigating Cold War tensions to secure their freedom without escalating conflict. He pioneered UN peacekeeping, deploying “blue helmets” to the Suez Crisis in 1956, where his creation of the UN Emergency Force defused a standoff between superpowers and regional players. In the Congo in 1960, he sought to stabilize a nation torn by post-colonial chaos, but his efforts drew sharp criticism. Many in the Global South viewed his interventions as too Western-leaning, misaligned with their aspirations for self-determination. His death in that plane crash—still plagued by credible suspicions of foul play, with UN investigations as recent as 2019 suggesting possible conspiracy—underscores the risks he faced. His principles didn’t always yield clean victories, but they gave him the spine to stand up to Soviet demands for his resignation and Western skepticism, redefining the UN as a neutral force.

The personal toll of this vocation was immense. Markings reveals a man haunted by isolation, carrying the weight of global crises in solitude. “Pray that your loneliness may spur you to find something to live for, great enough to die for”, he wrote, turning his solitude into a discipline rather than an escape. Elsewhere he confessed, “Alone. But solitude can be a communion”, suggesting that even in the wilderness of responsibility he could glimpse companionship with the eternal. Yet he did not romanticize the cost: “The anguish of loneliness brings drafts from the storm center of the anguish of death”.

As Secretary-General, Hammarskjöld bore that loneliness as part of his calling: late nights negotiating ceasefires, relentless travel through war zones, and decisions that could ignite or quell conflict. His vocation required not only public resilience but also private endurance—the discipline of carrying burdens no one else could share. This inner strength, hidden from the world, transformed his leadership from a performance of diplomacy into a solitary offering—a life quietly spent in service to a fractured world he sought to heal.

Hammarskjöld’s inner life was steeped in Christian mysticism, drawing from Meister Eckhart and Thomas à Kempis. “Faith is God’s union with the soul”, he wrote, envisioning himself as a vessel for divine purpose: “The vessel. The drink is God’s. And God is the thirsty one”. Nature was his sanctuary, where he found the divine pulse: “A landscape can sing about God, a body about spirit”. Mountains, forests, and silence were wellsprings of clarity.

His mysticism wasn’t withdrawal. Yet his introspection could border on obsession, and his uncompromising attitude on principles sometimes strained alliances. Still, that inner fire allowed him to redefine the UN’s role, pushing for neutrality, to navigate crises like Suez or face down Khrushchev, even when the world’s weight pressed hard.

Sixty years later, as global institutions falter and trust erodes, Hammarskjöld’s life is a gut check for leaders. He urged authenticity above all: “What you must dare—to be yourself. What you could achieve—that life’s greatness might be mirrored in you according to the measure of your purity”. He rejected the temptation to compromise for “peace and quiet”, knowing that betraying one’s truth was a defeat deeper than any external loss.

“What you must dare—to be yourself. What you could achieve—that life’s greatness might be mirrored in you according to the measure of your purity”

Markings is not an easy book. Its austere tone and exacting standards don’t flatter or coddle. For diplomats, public servants, or anyone bearing responsibility, it’s a raw, unflinching guide to moral grit. Hammarskjöld gave the UN a model of independence, demonstrating how a leader from a small nation like Sweden could wield the organization’s platform to shape global outcomes.

His legacy is not without blemish, yet his most intimate writings reveal a deeper truth: leadership is not measured by flawless victories or exalted positions, but by the struggle with one’s own failings, the strength drawn from quietude, and the resolve to serve with integrity. Moral authority, Hammarskjöld teaches, flows not from position or rhetoric but from the courage to confront your weaknesses and give yourself away for others. His life challenges us to treat service as a spiritual discipline—to prioritize truth over expediency, humility over pride. Read Markings to meet the man: not a hero, but a human who tried to bridge the divine and the earthly, and paid the ultimate price. [GC] ◳

Read Markings to meet the man: not a hero, but a human who tried to bridge the divine and the earthly, and paid the ultimate price.

Postscript

Just months before his fatal flight, on Whitsunday 1961, Dag Hammarskjöld recorded in Markings what reads like a final meditation on service and sacrifice.

I don't know Who-or what put the question, I don't know when it was put. I don't even remember answering. But at some moment I did answer Yes to Someone or Something and from that hour I was certain that existence is meaningful and that, therefore, my life, in self-surrender, had a goal. From that moment I have known what it means "not to look back," and "to take no thought for the morrow."

Led by the Ariadne's thread of my answer through the labyrinth of Life, I came to a time and place where I realized that the Way leads to a triumph which is a catastrophe, and to a catastrophe which is a triumph, that the price for committing one's life would be reproach, and that the only elevation possible to man lies in the depths of humiliation.

After that, the word "courage" lost its meaning, since nothing could be taken from me. As I continued along the Way, I learned, step by step, word by word, that behind every saying in the Gospels stands one man and one man's experience, Also behind the prayer that the cup might pass from him and his promise to drink it. Also behind each of the words from the Cross.

[1961:5] Dag Hammarskjöld