Beethoven or a Netflix Series: What Future for Multilateralism?

Beethoven’s Ninth turned suffering into universal harmony—a vision multilateralism once aspired to echo. Now, that moral music weakens under trends and slogans. Can the concert hall of nations recover its universal score—or will it simply binge what’s next?

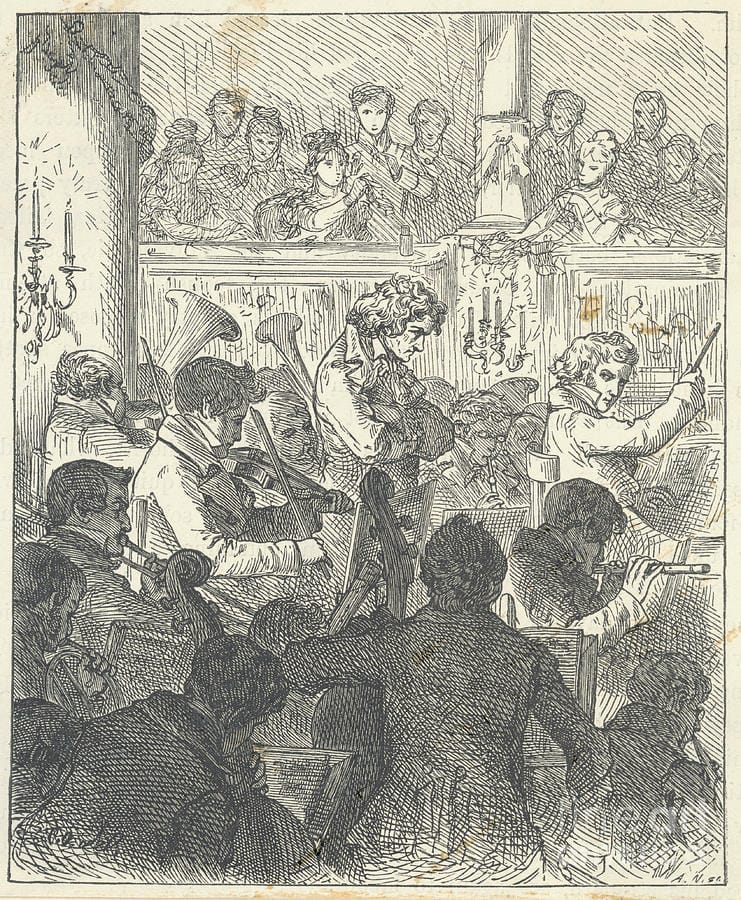

On May 7, 1824, at Vienna’s Kärntnertor Theater, an aging Beethoven stood before an orchestra performing a masterpiece he could no longer hear. The Ninth Symphony—his final and most daring work—unfolded around him, conducted in practice by Michael Umlauf while Beethoven, deaf and absorbed, stood behind. When the last triumphant notes of Schiller’s Ode to Joy resounded, the composer still faced the musicians, unaware. Only when the contralto Caroline Unger touched his arm and turned him toward the audience did he see what he could not hear: a hall risen to its feet, handkerchiefs waving, applause thundering in silent motion.

It was a moment suspended between isolation and communion—a man cut off from the world yet summoning it with universal harmony. Out of his deafness emerged not despair but vision: a music that reached beyond solace toward the eternal—an aspiration shared by humankind made audible.

The United Nations, founded amid the ruins of the Second World War, emerged from the same moral horizon that inspired Friedrich Schiller’s An die Freude (Ode to Joy, 1785)—a vision of humanity reconciled beyond class, creed, and nation. Schiller’s poem, later immortalized in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1824), celebrates the capacity of joy to bind together “what custom strictly divided” (Was die Mode streng geteilt), culminating in the line “Alle Menschen werden Brüder”—“All men shall become brothers.” Its ideal of unity through shared moral feeling anticipated, in poetic form, the principles later codified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Both works emerged from moments of historical fracture and sought to transform suffering into solidarity, proposing that reason and empathy could restore order where power had failed.

Both works emerged from moments of historical fracture and sought to transform suffering into solidarity, proposing that reason and empathy could restore order where power had failed.

While Schiller’s Ode to Joy envisioned a metaphysical fraternity “beneath the gentle wings” of joy (Wo dein sanfter Flügel weilt), the United Nations sought to translate that moral aspiration into institutional form. The Charter’s opening promise to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” (UN Charter, 1945) echoed not only the Enlightenment’s faith in universal reason but also older moral traditions—classical, Christian, and humanist—that understood harmony as the fruit of order, virtue, and self-restraint. Beethoven’s symphony was that inheritance made sound: disciplined joy wrought from struggle, freedom achieved through form. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights became its civic counterpart—a legal composition built on the belief that peace requires a moral grammar deeper than politics (UDHR, 1948).

But the contrast with the present is stark. The quiet struggle for shared meaning—the labor of bringing humanity closer through discipline, reason, and faith—has given way to a fragmented culture that equates emotion with understanding and novelty with truth. The concert hall of nations now resembles a streaming platform: the enduring supplanted by the topical. Where once diplomats appealed to the “inherent dignity” of the human person (UDHR, Preamble), agencies trade in slogans—narrative change, innovation, inclusivity—as if the human condition could be rebranded. What Schiller called “the sacred circle” (den heil’gen Zirkel dichter)—the fraternity of those sworn to truth—has been replaced by a marketplace of fleeting sympathies.

At the founding of the United Nations, the central debates were not about programs or funding cycles but about the moral foundations of peace. Among those who shaped that early conversation was Charles Malik, a Lebanese philosopher, diplomat, and one of the principal architects of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Trained in philosophy under Alfred North Whitehead at Harvard, Malik brought to diplomacy a conviction rare even then: that international order depended not only on treaties or balance of power, but on the integrity of the human spirit. In his 1962 work Man in the Struggle for Peace, he warned that “there is plenty of material injustice in the world, but intellectual and spiritual injustice is infinitely more significant.” For Malik, the gravest danger was not war itself, but the cultural exhaustion that precedes it—a civilization that forgets what it is defending and reduces the person to management rather than meaning.

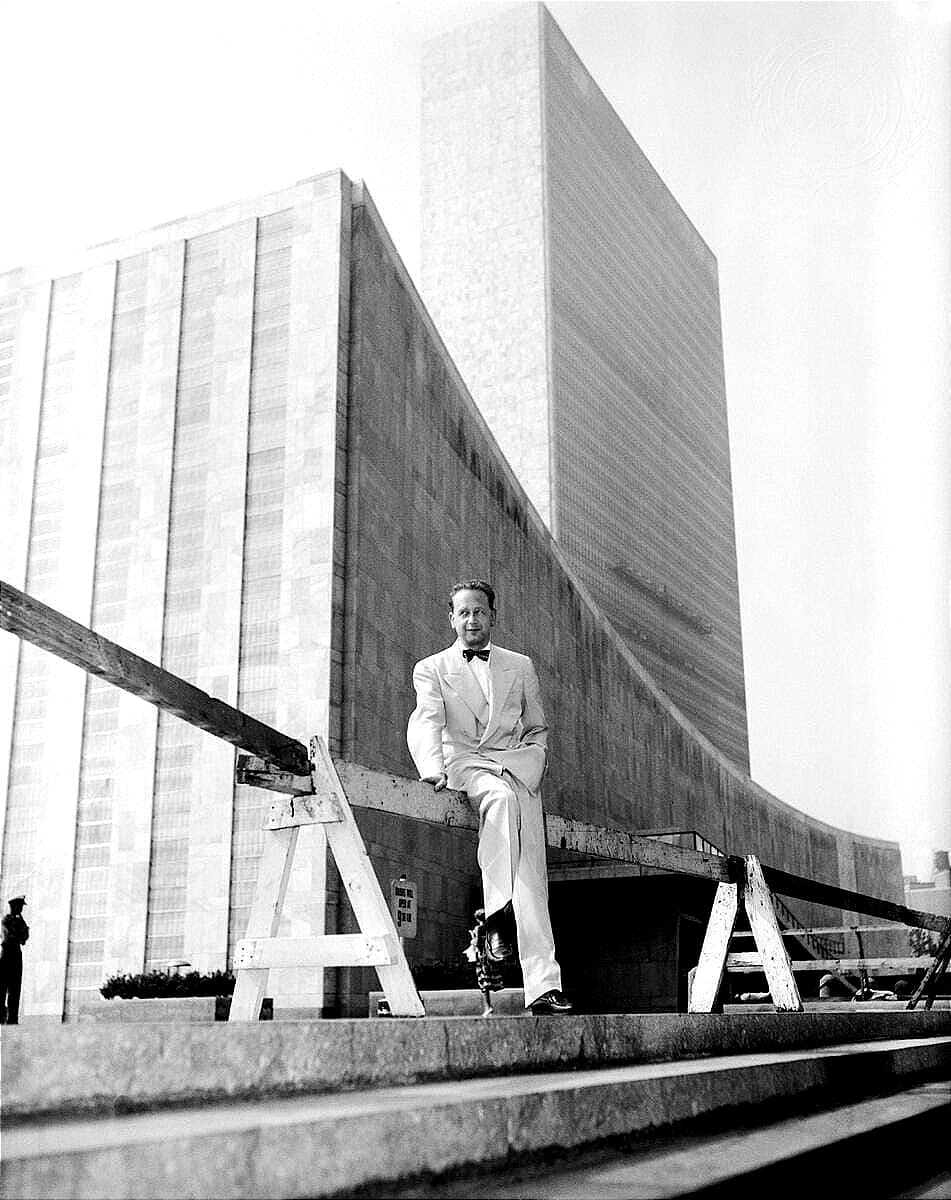

It was the same danger that Dag Hammarskjöld, the UN’s second Secretary-General, sought to resist through his conviction that diplomacy must remain “an outward expression of an inner condition.” As we explored in our Concordia Discors essay on Hammarskjöld’s spiritual realism, his vision of service—rooted in silence, conscience, and humility—was an attempt to preserve the moral interior of multilateralism. Where Malik appealed to philosophy and reason, Hammarskjöld answered through solitude and faith; both saw that the UN’s true crisis was spiritual. Once the Organization ceases to serve the inner life of humanity, it becomes merely an instrument of administration—a machine of procedures without purpose, managing the world but no longer inspiring it.

Both men, in different idioms, warned that once the UN ceases to serve the inner life of humanity, it becomes only an instrument of administration, not of meaning.

The contrast with Schiller’s universality is illuminating. For Schiller, “joy” was not mere sentiment but the felt rhythm of moral order—the harmony that emerges when human freedom aligns with the deeper laws of creation. When he wrote that “Freude treibt die Räder in der großen Weltenuhr” (“Joy drives the wheels of the great world-clock”), he was describing a cosmos governed by reason and proportion, in which joy is the sign that freedom and necessity have been reconciled. In Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795), Schiller argued that beauty performs this same reconciliation: it makes law lovable, and liberty lawful. “In beauty,” he wrote, “man discovers freedom in appearance”; in joy, he senses that harmony made real. The “world-clock” thus symbolizes a moral physics—freedom sustained by order, sentiment disciplined by form.

That insight anticipates the moral logic underlying the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Schiller would have seen in the UN’s founding not a triumph of sentimentality but an act of aesthetic reason—a political attempt to restore harmony after catastrophe. Like his “aesthetic state,” the postwar order sought to civilize freedom through shared measure. The Declaration’s first article begins not with rights as claims, but with an anthropology: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights… endowed with reason and conscience.” This premise—dignity as the balance between freedom and reason—is precisely the moral geometry Schiller described. What he achieved in the moral imagination, the drafters of 1948 attempted in the realm of law: to bind liberty to form, feeling to proportion, humanity to measure. Both are monuments to universality disciplined by structure—proof that true freedom is not the absence of constraint, but the harmony of conscience and order.

Both are monuments to a fragile universality: freedom achieved not through unbounded emotion but through self-limiting form, through the rediscovery of measure after catastrophe.

Universality is not an invention of some countries, but an inheritance of humanity. From Aristotle’s logos to Cicero’s lex naturae, from the Christian imago Dei to the Confucian ren and the Islamic fitra, civilizations have shared one conviction: that human worth does not depend on circumstance. The Declaration condensed that conviction into law.

Today, that universalism is fraying—not from rejection but from dilution. The United Nations increasingly speaks the language of marketing. Its campaigns are creative but transient; its conferences are energetic but forgettable. The institutional rhythm mirrors the algorithmic feed: endless, reactive, distracted.

This is the Netflix effect of governance—what might be called playlist universalism. Every season brings a new theme: digital rights, climate rights, reproductive rights, algorithmic governance, narrative transformation. Each cause contains truth and urgency; together, they reflect humanity’s restless search for justice. Yet pursued without reference to a common foundation, they risk dissolving the moral architecture that once made them meaningful.

The original canon of universality—the moral grammar of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—was narrow by design and vast in implication. It defined the essentials without which no civilization can claim to be humane: the sanctity of life, the freedom of conscience, the equality of persons before the law, and the absolute prohibitions of slavery and torture. These were not contingent rights but ontological affirmations, grounded in what Jacques Maritain called “the natural law written in the human heart.” They were meant to unite peoples divided by creed or system around a minimal but indestructible core.

These were not contingent rights but ontological affirmations, grounded in what Jacques Maritain called “the natural law written in the human heart.” They were meant to unite peoples divided by creed or system around a minimal but indestructible core.

That canon’s power lay precisely in its restraint. It was universal because it was elemental. Expansion without deepening, however, transforms universality into advocacy—an ever-growing catalogue of entitlements detached from their metaphysical roots. When the language of rights multiplies faster than the understanding of the person, meaning thins, coherence fades, and the moral energy that animated the UN’s founding dissipates into slogans. The result is governance by trend: eloquent, well-intentioned, but increasingly hollow.

That canon’s power lay precisely in its restraint. It was universal because it was elemental. Expansion without deepening, however, transforms universality into advocacy—an ever-growing catalogue of entitlements detached from their metaphysical roots.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) embody both the promise and the peril of modern multilateralism. They have galvanized unprecedented cooperation across governments, corporations, and civil society, translating broad moral aims into actionable commitments. Yet, as the UN’s most branded agenda, they risk transforming ethical vision into managerial routine. “Zero hunger” and “quality education” are noble aspirations, but when ideals are rendered as indicators, ethics begins to sound like accounting. The danger lies not in measurement itself but in moral reductionism: when what counts replaces what matters. Metrics can inspire progress, but they cannot define purpose. A civilization that measures everything may eventually forget why it measures at all. The UN’s task, therefore, is not to abandon the SDGs, but to recover the metaphysical horizon behind them—to remind the world that sustainable development is not merely a technical goal, but a moral vocation grounded in the dignity of the human person.

The danger lies not in measurement itself but in moral reductionism: when what counts replaces what matters. Metrics can inspire progress, but they cannot define purpose.

The crisis of multilateralism is, at heart, a crisis of essere—of being. The UN’s legitimacy depends on a conviction once taken for granted: that human dignity is real, not rhetorical; that it refers to something inherent in the person, not conferred by institutions or markets. Yet in an age of infinite feeds, the word “dignity” risks becoming a brand—declared, displayed, and discarded.

To recover its moral voice, the UN must recall what Beethoven and Schiller already knew: that the universal is not an aesthetic of inclusion but a metaphysics of being. Universality is demanding precisely because it binds; it imposes obligations on the strong as well as the weak, on nations no less than individuals.

To recover its moral voice, the UN must recall what Beethoven and Schiller already knew: that the universal is not an aesthetic of inclusion but a metaphysics of being.

As Pope John XXIII taught in Pacem in Terris (§30): “To claim one’s rights and ignore one’s duties, or only half fulfill them, is like building a house with one hand and tearing it down with the other.” The encyclical’s argument was not limited to private morality. John XXIII linked the recognition of rights to the maintenance of an international order “founded on truth, built up on justice, nurtured and animated by charity, and brought into effect under the auspices of freedom.” (§167). In other words: the stability of peace depends on the metaphysical balance between rights and responsibilities, freedom and truth, sovereignty and solidarity.

The same holds for multilateralism today. Rights without duties, freedom without truth, cooperation without conscience—these cannot last. The UN Charter itself presupposes this anthropology when it calls on states “to practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours.” To rediscover essere does not mean theologizing diplomacy; it means remembering that every durable political order rests on an understanding of what the human person is. The person—not the algorithm, not the ideology—is the measure of all governance.

To rediscover essere does not mean theologizing diplomacy; it means remembering that every durable political order rests on an understanding of what the human person is.

If the United Nations is to be Beethoven rather than Netflix, it must recover its vocation as a concert hall for conscience—a place where nations, despite discord, still learn to listen to one another in a common key. The challenge is not Western or Eastern, liberal or conservative; it is human. Universality is not ideology but architecture—the moral framework that lets difference coexist without domination. Small and mid-sized nations need it as a shield against arbitrary power; great powers as predictability that restrains rivalry; plural societies as a language that protects conscience without coercion; and the global South as legitimacy, proof that the UN is a moral dialogue, not a cultural monologue.

But universality cannot be sustained by charters alone—it lives through those who serve it. To “aim higher” is not to idealize diplomacy, but to recover its depth: to speak truth when silence is easier, to defend principle when consensus is cheap, to remember that compromise has meaning only when anchored in conviction. Not every report must be a new Ninth Symphony, but that should be the spirit animating the Organization’s work: disciplined universality, a harmony wrought from struggle. In an age of institutional fatigue, the UN’s task is not to chase novelty but to cultivate altitude—to become again a place where human beings, not algorithms or ideologies, deliberate on what binds us all. The value of multilateralism lies precisely here: in offering those who serve it the chance to think higher, to act from conscience, and to rediscover, together, the universal music of peace.

In an age of institutional fatigue, the UN’s task is not to chase novelty but to cultivate altitude—to become again a place where human beings, not algorithms or ideologies, deliberate on what binds us all.

Such measures do not theologize the UN—they pluralize it properly, grounding universality in shared being rather than shifting trends. But to recover this universality, the UN must also reform how it works from within. The Organization’s renewal will not come from new slogans or task forces, but from re-centering deliberation on enduring principles. Policy debates should once again begin from the human question: what kind of person, what kind of society, does this serve? Country reports, resolutions, and field missions must rediscover moral architecture—clarity of purpose, continuity of language, and respect for truth. The measure of success cannot be the number of initiatives launched, but the depth of understanding achieved. A bureaucracy animated by conscience, even in small gestures—accurate language, intellectual rigor, courage to name wrongdoing—can restore legitimacy more effectively than any new campaign. In that sense, reform begins not with systems but with souls: with officials who remember that their vocation is not management, but stewardship of meaning.

A bureaucracy animated by conscience, even in small gestures—accurate language, intellectual rigor, courage to name wrongdoing—can restore legitimacy more effectively than any new campaign. In that sense, reform begins not with systems but with souls: with officials who remember that their vocation is not management, but stewardship of meaning.

When Schiller wrote “Alle Menschen werden Brüder”—“All men shall become brothers”—he meant not sentimentality but discipline: a moral order sustained through struggle. Beethoven’s deafness transformed that conviction into sound—joy as the echo of truth, harmony as the reward of fidelity. The United Nations was conceived in that same spirit.

Its Charter and Declaration were not meant to mirror the world but to orient it—to be, as Paul VI told the General Assembly in 1965, “the obligatory path of modern civilization and of world peace… the great school where humanity learns peace.” The UN, he said, is a reflection of “God’s design… full of love for the progress of human society on earth.” That vision remains urgent: the Organization was never meant to please every age, but to instruct it.

The danger today is not dissonance but amnesia—a world that forgets the moral score it was meant to play. If the UN chases novelty, it will become a Netflix series of noble sentiments—each episode briefly compelling, none enduring. But if it recovers its sense of essere—the truth that precedes politics—it can again lead humanity, as Beethoven once did, from dissonance to universal joy.

The choice is ours: Beethoven or the binge. A score we learn to play together—or an endless playlist that plays us. ◳