America’s Polarization | Immigration: Borders and Belonging I

Immigration isn’t just about laws or numbers—it’s about identity. Borders symbolize sovereignty for some, compassion for others. The Mind’s Divide uncovers the hidden logics behind the clash—and asks how recognition, not contempt, can keep democracy whole.

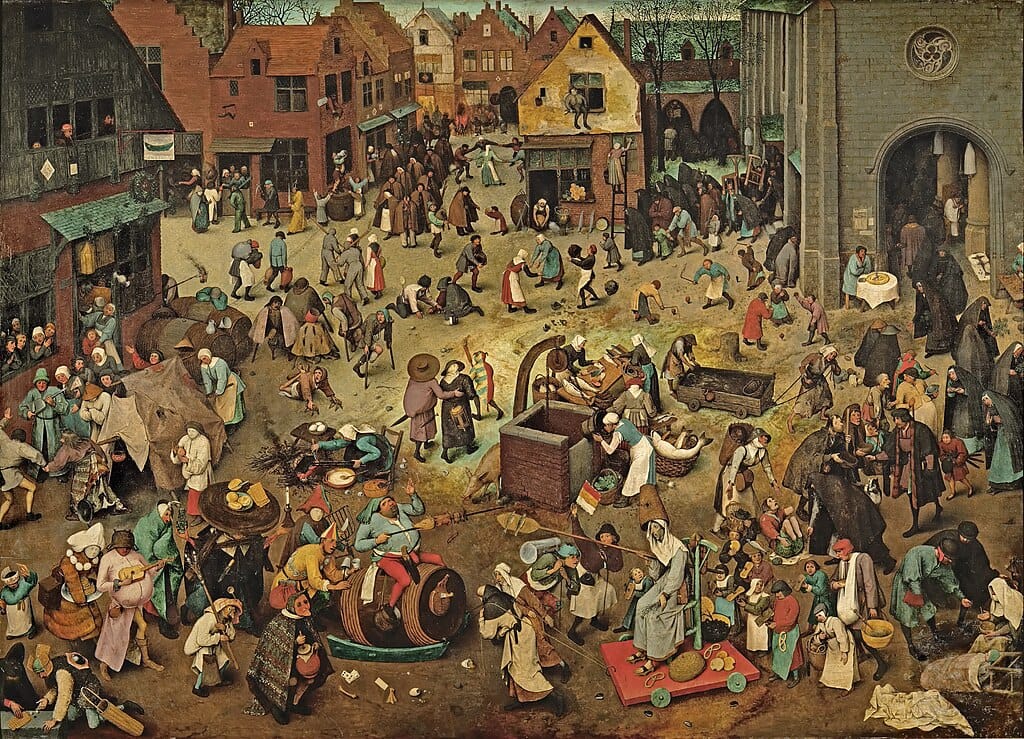

Pluralism means acknowledging that sovereignty and compassion are both genuine goods, but in tension. The tragedy of contemporary American politics is that it treats them as exclusive—transforming disagreement into existential struggle. (Concordia Discors Magazine)

Immigration has always been a constant in American life. Unlike Europe, where large-scale migration surged only in recent decades, the United States has long defined itself as a nation of immigrants—its mythology shaped by Ellis Island, its politics marked by successive waves of newcomers who became integral to the national fabric. That history makes today’s polarization all the more striking: the quarrel is not about whether immigration exists, but about what meaning it carries.

The intensity of the dispute cannot be explained by short-term flows alone. Border apprehensions rose sharply in the late 1970s, declined in the early 2000s, and fluctuated again in the 2010s. Net migration from Mexico turned negative between 2009 and 2014, while arrivals from Asia and Central America increased. Each of these shifts produced headlines, but none created the existential clash of recent years.

What changed is not the phenomenon but the frameworks through which Americans interpret it. For some, immigration is read primarily through the lens of sovereignty and loyalty: the border is the household wall, and breaches signal betrayal. For others, it is read through the lens of care and fairness: the border is a threshold where human suffering must be met with dignity. Thus the same fact—a caravan of families arriving at the border—can be coded as evidence of chaos and lawlessness, or as a humanitarian emergency demanding compassion.

This divergence is not limited to immigration. It reveals how political identity now shapes the way information itself is processed. The same set of facts is absorbed into different moral grammars, producing opposite conclusions. In that sense, immigration is not the outlier but the paradigm case of America’s polarization: an enduring issue transformed into an existential struggle because citizens no longer argue over the same questions, but over different questions altogether.

Immigration is no longer a technical dispute over quotas or visas; it has become a symbolic struggle over identity, sovereignty, and moral obligation.

The trade-offs come into sharp relief in the lives of ordinary citizens. Along the Rio Grande, ranchers in Uvalde and Kinney Counties have spoken of fences repeatedly cut, livestock scattered, and property damaged by migrants crossing their land—costly disruptions that translate national debates into daily insecurity. “Every time a fence is cut, we have to round up cattle and repair it ourselves,” one rancher told The Texas Tribune in 2023, framing the crisis less as abstract politics than as an existential strain on livelihoods built over generations. For these communities, sovereignty is not a slogan; it is the difference between stability and disorder in their own backyards.

Yet far from the border, another moral reality emerges. In late 2023, Chicago parishes and community groups began turning fellowship halls into temporary shelters for Venezuelan families bused north from Texas. Volunteers described their work not in partisan terms but as fidelity to faith and neighborhood solidarity: feeding children, providing winter coats, restoring dignity. As The Chicago Sun-Times reported, congregants saw the effort as living out the city’s immigrant legacy, recalling earlier generations who arrived poor and unwelcomed but who nonetheless built lives and neighborhoods. Here compassion is not sentimental—it is rooted in memory, duty, and identity.

Neither story is wrong. Both are examples of people acting in good faith to protect what they love: one, the integrity of a home and a way of life forged through hard labor; the other, the dignity of vulnerable strangers seeking refuge. Immigration forces these goods into collision. That is why it polarizes: not because one side lacks morality, but because both hold values that are real, urgent, and at times irreconcilable.

What threatens democracy is not the clash of these commitments but their exclusion from rational debate. When border communities are caricatured as merely xenophobic, or sanctuary volunteers dismissed as naïve, politics becomes incapable of seeing pluralism at work. As Isaiah Berlin warned, the attempt to flatten competing values into a single moral orthodoxy breeds extremism. A healthier democracy requires the opposite: keeping all voices in the conversation, precisely because their goods cannot be harmonized into one.

Immigration, then, dramatizes the mind’s divide: rival logics that make each side coherent to itself yet alien to the other. To name those logics is to recognize our opponents not as irrational, but as reasoning from different moral starting points. That recognition will not erase conflict. But it may keep conflict from curdling into contempt—and in that lies the survival of democratic life.

At the core of the immigration divide are two rival metaphors of the nation, operating largely below conscious awareness. Cognitive linguist George Lakoff described them as family models: one, the Strict Father household; the other, the Nurturant Parent community. These are not policy positions but moral archetypes that structure how citizens imagine government itself.

The conservative frame sees America as a household under threat. Borders are the walls of the home, discipline and rules are safeguards, and loyalty is owed to family members first—citizens. From this perspective, unauthorized entry is not primarily about economic impact but about violation, disorder, and betrayal. The duty of government, like a strict father, is to protect and punish. This frame resonates with what Samuel Huntington once called the “Anglo-Protestant core” of American identity (Who Are We?, 2004)—a cultural inheritance that conservatives see as fragile in the face of demographic change.

The progressive frame imagines America as a nurturing community. The nation is defined not by exclusion but by welcome, its very identity bound to the immigrant story. Borders are thresholds to be managed with compassion, not absolute walls. Government, like a caring parent, is responsible for dignity and fairness, extending welcome to those fleeing harm. Here the logic echoes John Rawls’s notion of justice as fairness and Martha Nussbaum’s “capabilities approach”—the view that societies are judged by how they protect the vulnerable and enable human flourishing.

These frames endure because they tap into different moral foundations. As Jonathan Haidt has argued in The Righteous Mind (2012), conservatives draw from a broader moral palate—loyalty, authority, sanctity—while progressives emphasize care, fairness, and liberty. Thus the same image—a family wading across the Rio Grande—can be coded in opposite ways: evidence of suffering that obliges compassion, or evidence of lawbreaking that demands enforcement.

Thus the same image—a family wading across the Rio Grande—can be coded in opposite ways: evidence of suffering that obliges compassion, or evidence of lawbreaking that demands enforcement.

What intensifies the conflict is that both sides elevate their values to the status of absolutes. For many progressives, the universalism of human rights overrides national boundaries; anything less is cruelty. For many conservatives, sovereignty and order are non-negotiable; anything less is betrayal. Each side thus treats the other not as choosing differently among legitimate goods, but as rejecting morality altogether.

Isaiah Berlin’s warning remains prescient: “We are faced with choices between ends equally absolute, the realization of some of which must inevitably involve the sacrifice of others” (Two Concepts of Liberty, 1958). Pluralism means acknowledging that sovereignty and compassion are both genuine goods, but in tension. The tragedy of contemporary American politics is that it treats them as exclusive—transforming disagreement into existential struggle.

Pluralism means acknowledging that sovereignty and compassion are both genuine goods, but in tension. The tragedy of contemporary American politics is that it treats them as exclusive—transforming disagreement into existential struggle.

Political scientist Lilliana Mason calls this dynamic “stacked identities” (Uncivil Agreement, 2018). When partisanship fuses with race, religion, geography, and cultural markers, every debate—immigration most of all—feels like a test of one’s entire way of life. That is why facts rarely persuade: they are absorbed into worldviews that are not just political but existential. The border becomes not a policy problem but a mirror of who “we” are—and who we fear becoming.

That is why facts rarely persuade: they are absorbed into worldviews that are not just political but existential. The border becomes not a policy problem but a mirror of who “we” are—and who we fear becoming.

This identity-laden dynamic explains why facts alone rarely persuade. Political psychologists note that evidence is not processed in a neutral vacuum but filtered through what Dan Kahan calls cultural cognition: people interpret data in ways that affirm their group identity.

Thus when progressives cite studies showing that immigration correlates with lower crime rates or long-term economic gains, conservatives often dismiss the evidence. The core violation, for them, is not statistical but moral: unlawful entry undermines sovereignty, order, and respect for authority. Conversely, when conservatives emphasize the strain on schools, housing, or hospitals, progressives counter with data on immigrant entrepreneurship or demographic renewal. For them, the central harm is not fiscal but human—families torn apart, asylum-seekers endangered, dignity denied.

Each side, in other words, reasons within a distinct moral grammar. Facts that do not resonate with that grammar are not merely unconvincing—they are effectively invisible. As Cass Sunstein has shown in Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide (2009), groups under conditions of polarization amplify confirming evidence and dismiss the rest, producing parallel worlds of “truth.”

Bridging does not mean dissolving disagreement. In a pluralist society, values will clash. What bridging requires is the discipline of recognition—the ability to see the other side’s reasoning as human and intelligible, even when one remains firmly opposed. That recognition creates the space where democracy can function without contempt. Several strategies offer promise:

1. Moral reframing.

Persuasion works best when it speaks the other side’s moral language.

- Progressives can emphasize fairness as proportionality: an orderly system rewards those who follow the rules and denies advantage to cartels or queue-jumpers. Framed this way, border management becomes not only an act of compassion but also of justice and authority.

- Conservatives can emphasize care: chaos at the border exposes families to traffickers, desert crossings, and exploitation. Firm enforcement, combined with lawful pathways, protects dignity and preserves life.

By translating values into each other’s terms, both sides can move from moral dismissal to moral recognition.

2. Institutional design.

Polarization intensifies when institutions amplify zero-sum dynamics. New designs can lower existential threat by giving each side part of what it seeks.

- Surge immigration courts with statutory deadlines would reduce backlogs and project a sense of order.

- State–federal resettlement compacts could tie local capacity to federal funding, reducing the resentment of communities who feel abandoned.

- Worksite enforcement paired with visa expansion would cut the shadow labor market while channeling economic demand into legal avenues, serving both rule-of-law and humanitarian aims.

Such designs acknowledge competing goods rather than pretending one side must vanish.

3. Narrative cues.

Language frames moral reality. Leaders who combine terms that normally divide can reach across moral grammars. Phrases like “orderly and humane” or “citizens first means cities that function” avoid the trap of binary coding. They remind citizens that enforcement can serve compassion, and compassion can serve stability.

Immigration will always provoke argument—and in a democracy, it should. To govern is to navigate tragic trade-offs: expanding compassion may strain sovereignty; reinforcing sovereignty may deny compassion. Both are real goods; neither can be permanently sacrificed without injury to the body politic. The danger arises not from conflict itself, but from the refusal to recognize its legitimacy. Isaiah Berlin warned that the denial of pluralism—the insistence on a single final solution to moral conflict—is the seedbed of extremism. Pluralism does not dissolve disagreement; it insists that disagreement remain within the bounds of recognition.

To govern is to navigate tragic trade-offs: expanding compassion may strain sovereignty; reinforcing sovereignty may deny compassion. Both are real goods; neither can be permanently sacrificed without injury to the body politic.

Immigration, more than almost any other issue, dramatizes the mind’s divide: rival logics that make each side coherent to itself yet alien to the other. To name those logics is to see that our opponents are not irrational, but reasoning from different moral starting points. That recognition does not end the conflict. But it can prevent it from curdling into contempt—and in that lies the survival of democratic life.